James Geary, NF ’12, editor of Nieman Reports, on the magazine’s founding

Due to lingering wartime shortages, the February 1947 premiere issue of Nieman Reports was printed not on sleek magazine stock but on heavy white butcher paper, and because of a proofreading snafu, the articles were full of typos. An inauspicious start perhaps for what is today one of the oldest magazines in the U.S. specifically devoted to journalism.

Nieman Reports began, appropriately enough, at a Nieman reunion, in 1946. One outcome was the Society of Nieman Fellows, which decided to establish Nieman Reports. The editorial board was made up of, among others, Louis M. Lyons, NF ’39, A.B. Guthrie Jr., NF ’45, Robert Lasch, NF ’42, and William J. Miller, NF ’41, who also penned the cover story in that first issue: “What’s Wrong With the Newspaper Reader.” “The trouble with the American newspaper reader … is,” Miller, a reporter for Newsweek and the Cleveland Press, wrote, “that he does not like to read anything that forces him to think.”

Miller’s lament came at a time when journalism faced technological disruption—from broadcast media, specifically television. But then, just as now, blaming the consumer was not the solution. Miller’s alternative was a kind of analog Kickstarter campaign. In 1947, Miller and several hundred other writers, artists and photographers put up between $500 and $1,000 each to found “’47: The Magazine of the Year.” Walter Lippmann was one of the owners-contributors. The publication lasted only two years, but for Miller it proved an important point: “Any time a sufficient number of people become really dissatisfied with the daily newspaper they are getting, they can pool their money and roll their own.”

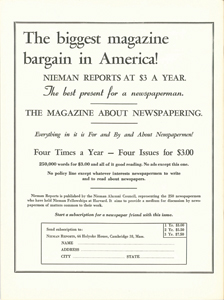

That’s essentially what the Society of Nieman Fellows did in starting Nieman Reports as “a quarterly about newspapering by newspapermen.” And that’s what today’s journalism innovators are doing in response to technological disruption. The challenges and opportunities remain very much the same. One other thing that hasn’t changed—Nieman Reports’ editorial mission, as defined by its founders: “It has no pattern, formula or policy except to seek to serve the purpose of the Nieman Foundation ‘to promote standards of journalism in America.’”