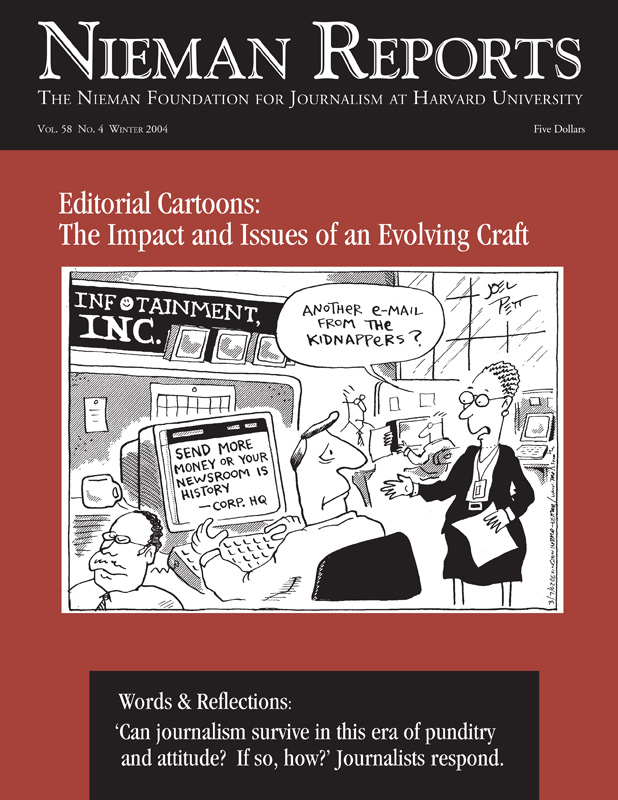

Certainly journalism will survive. Indeed, it could even thrive as a result of today’s very real challenges. Journalists need neither fear nor denounce the proliferation of punditry and attitude. Rather, as the media landscape teems ever more vigorously with partisanship and shout shows, infotainment, 24-hour-a-day repetitiousness and the near-anarchy of the Web world, journalism has a fine opportunity: To define itself in opposition to others. In the process, journalism could gain much-needed courage and clarity.

The evolutionary step made necessary by the growing dominance of viewpoints—along with the blending of entertainment and news and the ravages wrought by time pressure and profit pressure—is that some institutions and individuals must purposefully differentiate themselves according to a stated intention: Public service to citizens of this democracy. Through this principled differentiation, some will become known—and sought out—for their fairness and comprehensiveness, substantiality and proportionality, transparency and accountability.

Our increasingly attitude-driven media world is not all to the bad. The fastest-growing media sectors—alternative, ethnic and online media—are known for having a viewpoint. Clearly, they meet a hunger—even a public need. So do more partisan “mainstream” media, exemplified by Fox News. Ideological leanings are not themselves harmful. It is deceit that is wrong—the false presentation of one’s intentions. No one should be allowed to get away with hoodwinking the news consumer. Those who try should be called out—something clannish journalists have been disappointingly timid about doing.

But forthrightly partisan media have been important in our history—and remain so today elsewhere. In both cases, political engagement has been (or is) higher than here in the era of “objective journalism.” That same desirable result might well be repeating itself here today.

Accepting this reality doesn’t imply rejecting balanced and fair journalism; that is more needed than ever. But “objectivity” as a touchstone has grown worse than useless. For one thing, it is inadequate: Journalism has for decades been characterized in substantial part by interpretative and investigative and analytical reporting. To the extent that objectivity still holds sway, it often produces a report bound in rigid orthodoxy, a deplorably narrow product of conventional thinking. The cowardly, credulous and provincial coverage leading up to the Iraq War was a spectacular example. This orthodoxy also leaves out huge sectors of the population. Whatever the poverty of thinking of those in power, their views and actions are seen as legitimate, while thoughts and experiences of others are ignored. But if objectivity has become an ineffective and even harmful guide, it remains an extremely effective cudgel for those who wish to discredit the messenger on any story they disagree with. And the anticipation of these bludgeon-ings has produced a yet more craven media.

A forthright jettisoning of the “objectivity” credo, and a welcoming of the diverse media landscape springing up around us, could have freeing effects. Those who wish to get their news only from media sharing their viewpoint are welcome to it. Irreverent bloggers and alternative publications will increasingly make clear the true nature of those outlets. Meanwhile, the news sources seeking to serve the public interest with as much fairness and balance as possible will become differentiated from the others—thereby appealing to a growing hunger for guidance through an ever more bewildering media forest. Objectivity bludgeonings will lose their power. These media will contribute their varied strengths—from the net’s innovation and interactivity to cable news’s breaking-news preeminence. And the mainstream media wise enough to let the fresh air in, rather than fearfully shutting it out, will gain in clarity, strength and purposefulness from the democratization and the questioning and critiques that accompany the transition.

One more thought: With objectivity no longer the byword, transparency and accountability become ever more important—transparency of intent and also of procedure. And accountability of every kind, from ombudsmen to reader advisory groups, from state news councils to online chats. And amid the uncertainty, the best ethical guidance might be found in time-tested credos like this one written by Walter Williams at the beginning of the last century:

“I believe that the public journal is a public trust; that all connected with it are, to the full measure of responsibility, trustees for the public; that acceptance of lesser service than the public service is a betrayal of this trust.

“I believe that clear thinking, clear statement, accuracy and fairness are fundamental to good journalism.

“I believe that a journalist should write only what he holds in his heart to be true. I believe that suppression of the news, for any consideration other than the welfare of society, is indefensible.”

Nary a mention, you’ll notice, of objectivity.

Geneva Overholser, a 1986 Nieman Fellow, is the Curtis B. Hurley Chair in Public Affairs Reporting, Missouri School of Journalism, Washington bureau.