“Thought will spread across the world with the rapidity of light, instantly conceived, instantly written, instantly understood. It will blanket the earth from one pole to the other—sudden, instantaneous, burning with the fervor of the soul from which it burst forth.”

Those opening words would seem to describe, with the zeal typical of the modern techno-utopian, the arrival of our new online media environment with its feeds, streams, texts and tweets. What is the Web if not sudden, instantaneous and burning with fervor? But French poet and politician Alphonse de Lamartine wrote these words in 1831 to describe the emergence of the daily newspaper. Journalism, he proclaimed, would soon become “the whole of human thought.” Books, incapable of competing with the immediacy of morning and evening papers, were doomed: “Thought will not have time to ripen, to accumulate into the form of a book—the book will arrive too late. The only book possible from today is a newspaper.”

Lamartine’s prediction of the imminent demise of books didn’t pan out. Newspapers did not take their place. But he was a prophet nonetheless. The story of media, particularly the news media, has for the last two centuries been a story of the pursuit of ever greater immediacy. From broadsheet to telegram, radio broadcast to TV bulletin, blog to Twitter, we’ve relentlessly ratcheted up the velocity of information flow.

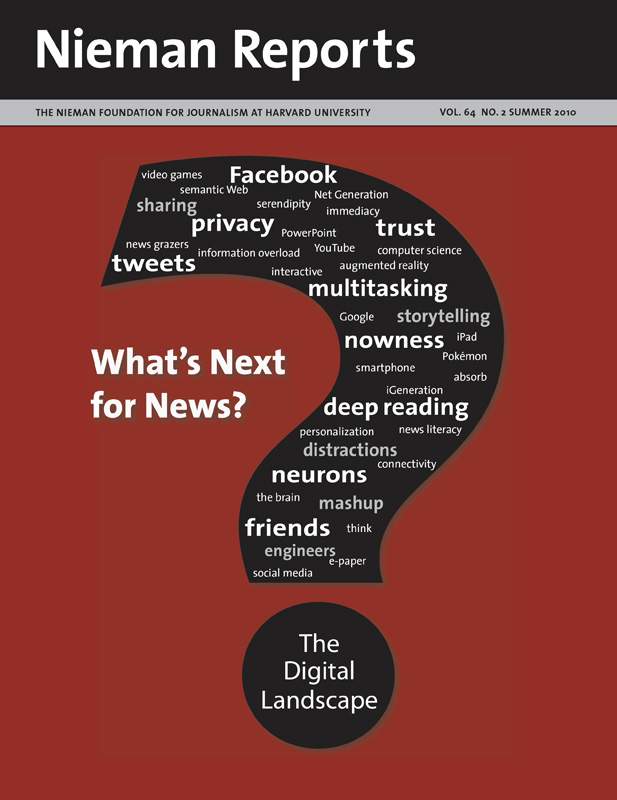

To Shakespeare, ripeness was all. Today, ripeness doesn’t seem to count for much. Nowness is all.

The daily newspaper, the agent of immediacy in Lamartine’s day, is now immediacy’s latest victim. It’s the newspaper that arrives too late. An enormous amount of ink, both real and virtual, has gone into diagnosing the shift of news from page to screen and the travails the shift inflicts on publishers and journalists. Yet when we take a longer view, the greatest threat to serious journalism may not be the Web. Instead, it may be found in changes already under way in the ways people read and even think—changes spurred by the Web’s rapid-fire mode of distributing information.

It used to be thought that our brains didn’t change much once we reached adulthood. Our neural pathways established during childhood, common wisdom held, remained fixed throughout our mature years. We know now that’s not the case. In recent decades, neuroscientists such as Michael Merzenich and Eric Kandel have shown that the adult brain is, as Merzenich puts it, “massively plastic.” The synaptic connections between our neurons are constantly reweaving themselves in response to environmental and cultural shifts, including the adoption of new information technologies. When we come to rely on a new medium for finding, storing, and sharing information, Merzenich explains, we end up with “different brains.”

Reading: Print to Web

For 500 years the medium of print has been training us to pay attention. The genius of a page of printed text is that nothing else is going on. The page shields us from the distractions that bombard us and break our concentration. The printed word allows us to “lose ourselves,” as we’ve come to say, in a book, a magazine essay, or a long newspaper article. Print journalism, at least in its more serious forms, has shaped itself to the attentive reader. The layout of a paper makes it easy to skim headlines, but it also assumes that the skimming is a means to an end, a way to discover stories that merit deeper reading and study. A newspaper allows us to scan and browse; it also encourages us to slow down.

The Web promulgates a very different mode of reading and thinking. Far from shielding us from distractions, it inundates us with them. When we turn on our computers and log on to the Net, we are immediately flung into what the writer Cory Doctorow calls an “ecosystem of interruption technologies.” The welter of online information, messages, and other stimuli plays, in particular, to our native bias to “vastly overvalue what happens to us right now,” as Christopher Chabris, a psychology professor at Union College, wrote in The Wall Street Journal. We rush toward the new even when we know that “the new is more often trivial than essential.”

RELATED ARTICLE

“Thinking About Multitasking: It’s What Journalists Need to Do”

-Clifford NassUnlike the printed page, the Web never encourages us to slow down. And the more we practice this hurried, distracted mode of information gathering, the more deeply it becomes ingrained in our mental habits—in the very ways our neurons connect. At the same time, we begin to lose our ability to sustain our attention, to think or read about one thing for more than a few moments. A Stanford University study published last year showed that people who engage in a lot of media multitasking not only sacrifice their capacity for concentration but also become less able to distinguish important information from unimportant information. They become “suckers for irrelevancy,” as one of the researchers, Clifford Nass, put it. Everything starts to blur together.

On the Web, skimming is no longer a means to an end but an end in itself. That poses a huge problem for those who report and publish the news. To appreciate variations in the quality of journalism, a person has to be attentive, to be able to read and think deeply. To the skimmer, all stories look the same and are worth the same. The news becomes a fungible commodity, and the lowest-cost provider wins the day. The news organization committed to quality becomes a niche player, fated to watch its niche continue to shrink.

The fervor of nowness displaces the thoughtfulness of ripeness.

There’s little chance that technology will reverse course. With the growing popularity of instant social media services like Facebook and Twitter, the Web is rapidly moving away from “the page” as the governing metaphor for the presentation of information. In its place we have “the stream,” a fast-moving, ever-shifting flow of bite-sized updates and messages. Everything we’ve seen in the development of the Net and, indeed, in the development of mass media indicates that the velocity of information will only increase in the future.

If serious journalism is going to survive as something more than a product for a small and shrinking elite, news organizations will need to do more than simply adapt to the Net. They’re going to have to be a counterweight to the Net. They’re going to have to find creative ways to encourage and reward readers for slowing down and engaging in deep, undistracted modes of reading and thinking. They’re going to have to teach people to pay attention again. That’s easier said than done, of course—and I confess that I have no silver bullet—but the alternative is continued decline, both economic and intellectual.

Nicholas Carr writes extensively about the social, cultural and economic implications of technology. His latest book, “The Shallows: What the Internet Is Doing to Our Brains,” was published in June by W.W. Norton. He is also the author of “Does IT Matter?” and “The Big Switch: Rewiring the World, from Edison to Google.”

Those opening words would seem to describe, with the zeal typical of the modern techno-utopian, the arrival of our new online media environment with its feeds, streams, texts and tweets. What is the Web if not sudden, instantaneous and burning with fervor? But French poet and politician Alphonse de Lamartine wrote these words in 1831 to describe the emergence of the daily newspaper. Journalism, he proclaimed, would soon become “the whole of human thought.” Books, incapable of competing with the immediacy of morning and evening papers, were doomed: “Thought will not have time to ripen, to accumulate into the form of a book—the book will arrive too late. The only book possible from today is a newspaper.”

Lamartine’s prediction of the imminent demise of books didn’t pan out. Newspapers did not take their place. But he was a prophet nonetheless. The story of media, particularly the news media, has for the last two centuries been a story of the pursuit of ever greater immediacy. From broadsheet to telegram, radio broadcast to TV bulletin, blog to Twitter, we’ve relentlessly ratcheted up the velocity of information flow.

To Shakespeare, ripeness was all. Today, ripeness doesn’t seem to count for much. Nowness is all.

The daily newspaper, the agent of immediacy in Lamartine’s day, is now immediacy’s latest victim. It’s the newspaper that arrives too late. An enormous amount of ink, both real and virtual, has gone into diagnosing the shift of news from page to screen and the travails the shift inflicts on publishers and journalists. Yet when we take a longer view, the greatest threat to serious journalism may not be the Web. Instead, it may be found in changes already under way in the ways people read and even think—changes spurred by the Web’s rapid-fire mode of distributing information.

It used to be thought that our brains didn’t change much once we reached adulthood. Our neural pathways established during childhood, common wisdom held, remained fixed throughout our mature years. We know now that’s not the case. In recent decades, neuroscientists such as Michael Merzenich and Eric Kandel have shown that the adult brain is, as Merzenich puts it, “massively plastic.” The synaptic connections between our neurons are constantly reweaving themselves in response to environmental and cultural shifts, including the adoption of new information technologies. When we come to rely on a new medium for finding, storing, and sharing information, Merzenich explains, we end up with “different brains.”

Reading: Print to Web

For 500 years the medium of print has been training us to pay attention. The genius of a page of printed text is that nothing else is going on. The page shields us from the distractions that bombard us and break our concentration. The printed word allows us to “lose ourselves,” as we’ve come to say, in a book, a magazine essay, or a long newspaper article. Print journalism, at least in its more serious forms, has shaped itself to the attentive reader. The layout of a paper makes it easy to skim headlines, but it also assumes that the skimming is a means to an end, a way to discover stories that merit deeper reading and study. A newspaper allows us to scan and browse; it also encourages us to slow down.

The Web promulgates a very different mode of reading and thinking. Far from shielding us from distractions, it inundates us with them. When we turn on our computers and log on to the Net, we are immediately flung into what the writer Cory Doctorow calls an “ecosystem of interruption technologies.” The welter of online information, messages, and other stimuli plays, in particular, to our native bias to “vastly overvalue what happens to us right now,” as Christopher Chabris, a psychology professor at Union College, wrote in The Wall Street Journal. We rush toward the new even when we know that “the new is more often trivial than essential.”

RELATED ARTICLE

“Thinking About Multitasking: It’s What Journalists Need to Do”

-Clifford NassUnlike the printed page, the Web never encourages us to slow down. And the more we practice this hurried, distracted mode of information gathering, the more deeply it becomes ingrained in our mental habits—in the very ways our neurons connect. At the same time, we begin to lose our ability to sustain our attention, to think or read about one thing for more than a few moments. A Stanford University study published last year showed that people who engage in a lot of media multitasking not only sacrifice their capacity for concentration but also become less able to distinguish important information from unimportant information. They become “suckers for irrelevancy,” as one of the researchers, Clifford Nass, put it. Everything starts to blur together.

On the Web, skimming is no longer a means to an end but an end in itself. That poses a huge problem for those who report and publish the news. To appreciate variations in the quality of journalism, a person has to be attentive, to be able to read and think deeply. To the skimmer, all stories look the same and are worth the same. The news becomes a fungible commodity, and the lowest-cost provider wins the day. The news organization committed to quality becomes a niche player, fated to watch its niche continue to shrink.

The fervor of nowness displaces the thoughtfulness of ripeness.

There’s little chance that technology will reverse course. With the growing popularity of instant social media services like Facebook and Twitter, the Web is rapidly moving away from “the page” as the governing metaphor for the presentation of information. In its place we have “the stream,” a fast-moving, ever-shifting flow of bite-sized updates and messages. Everything we’ve seen in the development of the Net and, indeed, in the development of mass media indicates that the velocity of information will only increase in the future.

If serious journalism is going to survive as something more than a product for a small and shrinking elite, news organizations will need to do more than simply adapt to the Net. They’re going to have to be a counterweight to the Net. They’re going to have to find creative ways to encourage and reward readers for slowing down and engaging in deep, undistracted modes of reading and thinking. They’re going to have to teach people to pay attention again. That’s easier said than done, of course—and I confess that I have no silver bullet—but the alternative is continued decline, both economic and intellectual.

Nicholas Carr writes extensively about the social, cultural and economic implications of technology. His latest book, “The Shallows: What the Internet Is Doing to Our Brains,” was published in June by W.W. Norton. He is also the author of “Does IT Matter?” and “The Big Switch: Rewiring the World, from Edison to Google.”