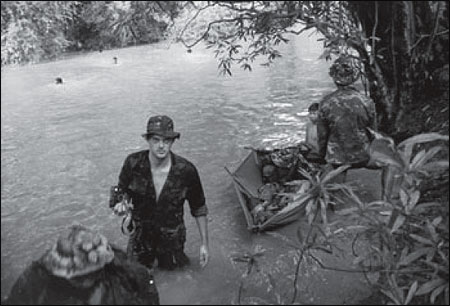

Thayer in a Khmer Rouge controlled area of Cambodia. Photo by Roland Eng.

At an annual gathering of the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists in July, I sat with Ahmed Rashid, a renowned Pakistani journalist, and discussed the decreasing appetite for international news. Rashid has spent a lifetime writing about Afghanistan. He spoke then of diminishing interest from editors for his stories. “No one is interested in Afghanistan anymore,” he concluded. His brilliant book, “Taliban: Militant Islam, Oil and Fundamentalism in Central Asia,” was newly published and was meeting with a good response from those who maintained an interest in this “irrelevant” corner of the world.

Typical for an accomplished and respected freelance journalist, Rashid writes for a number of publications, relying on a core handful of news organizations to make a living. But, he said in July, even these were rejecting stories they once would have published. The Islamabad-based Rashid said it was a struggle to get anything published on Central Asia in the British- and American-owned publications he relied on.

Only weeks later, after the events of September 11, I smile as I pass my small-town bookstore and see Ahmed Rashid’s “Taliban” prominently placed on a rack next to the cash register—number one on The New York Times bestseller list. I see Rashid regularly on television and quoted copiously by journalists now descending on the region—22 years after he began reporting full time from and about Afghanistan.

The pleasure is mixed with melancholy for the state of international reporting. Hundreds of freshly arriving foreign correspondents obscure the fact that they are often dispatched by major news organizations to cover international events only after they are overtaken by them. And their presence obscures the crucial role that local and freelance journalists play in ensuring that these otherwise forgotten places are properly covered in the absence of a major media presence.

Further, the key role played by “foreign” freelance journalists in providing the backbone of international coverage highlights the importance of the principle of a press free from the influence of any government. Many, if not most, of those who gather information for the American-owned press are not American. And many of those who read or view the American-owned press are not American. And for those who are, so what? The concept that reporters should have some allegiance to their government is not only fundamentally contrary to the role of a credible and independent press, it presupposes a false premise: that news organizations are homogeneously comprised of nationals of the country of which they have their primary audience.

It is freelancers and local journalists who are now playing a crucial role in Central Asia in ensuring that the world understands these events as they have rocketed to the forefront of international attention. When a story forces media executives to react to events, their reporters must turn to those who are informed and on the ground. Invariably, those they turn to are freelance local journalists such as Ahmed Rashid.

At the same time, the events of September 11 should have sent a cautionary signal to major media conglomerates, which increasingly are controlled by people who have demonstrated an insufficient commitment to the role of a free press and well informed public in world affairs. These news outlets are increasingly driven by their marketing departments, public relations people and lawyers, whose values too often infiltrate the newsrooms and effectively seize control. Non-journalists are increasingly determining what is news and treating it as a commodity, selling it like shampoo or cars.

The world press has indeed been absent from Central Asia since the Soviets and the CIA pulled out a decade ago. Before September 11, how many news organizations had staff reporters in Islamabad, much less in Kabul, or in the countries just north of Afghanistan? Precious few. Not The New York Times, The Washington Post, CNN, nor any other American news organization except The Associated Press (often staffed by “local hires,” usually nationals). Nor did the three American broadcast networks—which eviscerated their foreign news operations during the past decade—have staff correspondents in the region.

Lessons From Cambodia and Afghanistan

There are useful comparisons to be made between what is happening now in Afghanistan (and with Rashid’s reporting) and the decade I spent as a freelance reporter in Cambodia. Both Rashid and I had chosen areas of focus that often held marginal interest in the ebb and flow of international attention. Neither of us was a staff correspondent, though each was listed as a “senior writer” on the masthead of the Far Eastern Economic Review, the leading Asian weekly newsmagazine, owned by Dow Jones. Our compensation came primarily from our published words.

Like Afghanistan, Cambodia was, after a spurt of international focus, relegated to the dustbin of obscure civil wars. Interest in both countries always had little to do with the country itself, but rather the proxy role each played to larger global players. Once epicenters of cold war conflicts that served as a hot theater for foreign power interests, by the mid 1990’s neither Afghanistan nor Cambodia had much economic, political or strategic value to the world—or to its media.

Like the Taliban and bin Laden in Afghanistan, the Khmer Rouge and Pol Pot continued to play a major role in Cambodia’s politics after outside interest diminished. And, despite the absence of international attention, the domestic dynamics of these conflicts continued largely unchanged, ready to erupt. Like bin Laden, Pol Pot was seemingly an inaccessible enigma, directing a monstrous political movement and hiding in impenetrable terrain. And similar to Rashid’s predicament this past summer when I was a freelancer covering Cambodia, editors at my primary news outlets constantly discouraged me from pursuing stories and often rejected ones I wrote. These stories were dismissed as too obscure, costly, dangerous, or merely “uninteresting to our readers.”

Such reactions explain why there has developed such a dearth of in-depth international journalism. This essential yet expensive genre of reporting has few institutional supporters. Fortunately, as a freelancer I had the latitude (if not the expense account) to ignore those who urged me to stop my investigations. Had I been a staff reporter covering Cambodia—and therefore required to abide by instructions of those who had the right to dictate what stories I could pursue—I would not have kept reporting many stories that were deemed “important” as time went on.

The absence of coverage of these regions is usually a reflection of the skeletal resources that major media organizations devote to foreign coverage. And that is a decision often dictated by the business side. The Afghans and Cambodians, after all, aren’t likely to be promising advertising targets or subscribers. Therefore, the argument goes, there is little “reader interest.” And, in the absence of staff journalists based in such places, it can often appear that there is little of newsworthy significance. But, as the events of September 11 made clear, this is not necessarily true. There are important stories to tell and it is crucial for news organizations to be prepared to cover news properly when events demand.

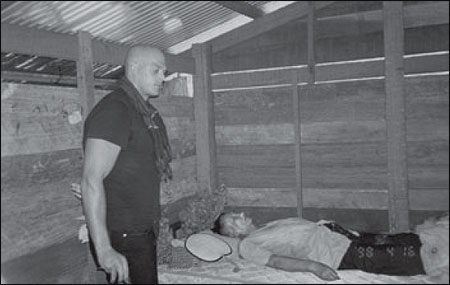

The author standing next to the body of Pol Pot.

The Role and Life of a Freelance Journalist

While publications naturally like to take credit for work they publish, any modicum of journalistic accomplishments I might have had were not wholly supported—financially or otherwise—by any publication. Freelancers usually must pay the expense of research, travel and phone upfront with no guarantees of having their work published or expenses reimbursed. Given the substantial costs of reporting, many stories go unreported for the simple reason that there aren’t journalists to do them.

It is true that properly covering many obscure and complicated conflicts often bears little immediate fruit. I emerged from most forays with precious little, often after weeks of work, an empty wallet, and thousands of kilometers of travel. But even though a meeting or trip would often not bear fruit worthy of an article, it all added up to a body of unique knowledge and access. My persistence, like the work of many freelancers, left me in good position to write knowledgeably when newsworthy events happened. Like most “local” journalists and freelancers, I had what visiting journalists did not—the essential context for any story, pertinent background and, after years of cultivation, well developed sources in place. At such moments, I could usually offer plausible and well informed analysis of what a news story meant.

Like many other reporters, I prefer to work as a freelancer, even though it’s a job that is often like being a mistress. The editors’ attitude: “Why buy the cow, if you can get the milk for free?” They compliment me profusely after each encounter and give me little stipends to keep me feeling wanted and coming back. They speak wistfully of how much they wish they could hire me and that someday we might have a permanent relationship. Like two illicit lovers who can’t look each other in the eye, we both generally leave our encounters satisfied. We each accept the arrangement as good under the circumstances. And I am fully aware that the focus of my reporting makes me rather unemployable by nature—not marriage material.

In June 1997, I was still a freelance journalist when Cambodia, again, imploded in civil war. Hundreds of journalists descended on the country. There were reports from the jungle suggesting Pol Pot was on the run, and fighting raged on several fronts throughout the country. I’d already spent years reporting in inhospitable jungles (though I’d been based in Phnom Penh and Bangkok), attempting to find Pol Pot, the leader of the Khmer Rouge.

I called editors seeking plane fare to go back to Cambodia. “I believe I might be able to get to Pol Pot,” I said. I was flatly turned down. I borrowed money and got on a plane that day. Six weeks later, I emerged from Khmer Rouge-controlled jungles having gotten to Khmer Rouge headquarters and been the only reporter to attend the “trial” of Pol Pot, one of the century’s most sought-after mass murderers. In 18 years he hadn’t been seen or photographed. For a couple of days, it became the biggest story in the world. And as a freelancer, I had the only firsthand reporting, still pictures, and video of the story.

I received thousands of calls from media wanting my pictures and story. As I sat in my office in Bangkok, journalists from the world’s major media descended like vultures. And before I’d even finished writing my story, these events were front-page news around the world. Ted Koppel of ABC News flew to Bangkok from Washington, and he returned home with a copy of my videotape. I gave it to him in exchange for his strict promise that its only use would be on “Nightline.” However, once he had the copy of the tape, ABC News released video, still pictures, and even transcripts of my interviews to news organizations throughout the world. Protected by its formidable legal and public relations department, ABC News made still photographs from the video, slapped the “ABC News Exclusive” logo on them, and hand delivered them to newspapers, wire services, and television. It also released the transcripts of my interviews to The New York Times and placed pictures and video on its Web site with instructions on how to download them. All of these pictures demanded that photo credit be given to ABC News.

Even though ABC News does not have a correspondent in Southeast Asia, it looked as though ABC News had gone and found Pol Pot. The Far Eastern Economic Review ran my story in its weekly edition a couple of days later. But already thousands of newspapers, magazines and television stations had published or broadcast the story, thanks to ABC News. The story won a British Press Award for “Scoop of the Year” for a British paper I didn’t even know had published it. The Wall Street Journal (also owned by Dow Jones), for which I’d never written about this story, also won several awards for its coverage. I even won a Peabody Award as a “correspondent for ‘Nightline.’” But I turned it down—the first time anyone had rejected a Peabody in its 57-year history. No one noticed, since ABC News banned me from attending the ceremony after I told Koppel I would reject the award.

When I watch the Afghan coverage and think about the U.S. military and American news reporters now looking vigorously for bin Laden, I remember that he has been interviewed and photographed seven times by local and freelance journalists. And when I see the American networks play “stolen” footage—obtained by Al-Jazerra and lifted off satellite transmitters—I think of the Al-Jazerra correspondents in Kabul, risking their lives and developing sources to obtain information and develop access. I am outraged that a U.S. smart bomb targeted their offices and there was scant protest. And when I see the Ken and Barbie news celebrities in their color-coordinated flak jackets reporting from the “front lines” (microphone in one hand, aerosol hair spray nearby), I picture them pouring at night over the life work of Ahmed Rashid to try to get an understanding of what the hell is going on.

With the war in Afghanistan, it is important to remember the invaluable role played by freelancers and local correspondents whose commitment to reporting gives substance to the current coverage. They play a pivotal role in maintaining a free press by delivering knowledgeable, firsthand, Wells information from the field. It is their dedication to this vital enterprise that creates the foundation for what we read and view, not the efforts of slick corporate hucksters and their willing agents who would substitute an agenda that betrays what should be our singular allegiance. That allegiance should not be to Pennsylvania Avenue, or to Wall Street, or to Madison Avenue. It should be to Main Street.

Nate Thayer was the Cambodia, then Southeast Asia, correspondent for the Far Eastern Economic Review. He has written for more than 40 other publications and news services and has won numerous awards, including the 1999 SAIS-Novartis prize for Excellence in International Journalism and the first award given by the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists.