On the afternoon of December 24, popular Chinese author Hao Qun, writing under the pen name Murong Xuecun, blogged that the average lifespan of a microblog account in China is now just about 10 hours. Exactly 26 minutes and 17 seconds later, censors had already wiped the posting from the Internet.

The speed with which posts are deleted is just one indicator of the Chinese government’s ability to muzzle freedom of expression, a trend that has sharply worsened in the year since President Xi Jinping came to power in November 2012. Xi took office at a time when people were becoming dissatisfied with the state of society and hopeful for political reform. Instead, the opposite has happened, with crackdowns on Chinese and foreign journalists becoming more frequent and online censorship increasing. People need to be on guard against “Western anti-China forces,” Xi warned in a speech in August, that “constantly strive in vain to use the Internet to overwhelm China.” “The new administration thinks the Internet is especially a threat to the regime,” says Michael Anti, a Chinese journalist and blogger. “That’s the reason they’ve cracked down more than ever before.”

Journalists at Southern Weekly, one of China’s most daring newspapers, went on strike in 2013 after state censors spiked a New Year’s editorial calling for China to respect constitutional rights, replacing it with platitudes about the Communist Party’s unique role in “the rejuvenation of the Chinese nation.” In December, some two dozen journalists from The New York Times and Bloomberg News waited anxiously to see if their journalist visas would be renewed while their news organizations scrambled to draw up contingency plans to cover China from Taiwan and Hong Kong. The journalist cards needed to obtain visas came in the final days of the year, but the message was clear: China is willing to deal harshly with any foreign reporters who cross it.

Foreign journalists face various forms of government intimidation, harassment, surveillance, a barrage of malware attacks, and in recent years visa intimidation

The Communist Party has long striven to control freedom of speech in China. Hundreds of thousands of websites from around the world are blocked inside China. Major social media, such as Facebook, Twitter, Wikipedia, and LinkedIn, cannot be accessed, and advanced software is used to search and destroy “sensitive” words on the Internet. “The authorities rely on secret security police to threaten individual citizens, to unceasingly harass and arrest citizens who express their freedom of expression through microblogs,” says Hu Jia, a prominent rights activist in Beijing, “and to create fear among bloggers and netizens to make everyone feel insecure and to self-censor and remain silent.”

Related Article

Eluding the “Ministry of Truth”

By Anne Henochowicz

The domestic media, more easily controlled, have fared even worse. Domestic journalists who step over the invisible line of what’s permissible face possible punishment, being fired or even arrested. Frequent orders are issued telling news organizations what they can and can’t publish, a system that has been dubbed “Directives from the Ministry of Truth.” Although the international media can’t be censored, foreign journalists face various forms of government intimidation, harassment, surveillance, a barrage of malware attacks that are believed to be the work of government agents, restrictions on their reporting, and in recent years visa intimidation aimed at encouraging self-censorship. The situation worsened considerably in 2013, as the new government tightened its grip.

Murong Xuecun, who had more than 8.5 million followers before his accounts were deleted, talks of his growing frustration, constantly having to wait long periods to see items appear online or then suddenly seeing them disappear. He is also afraid, though this has not stopped him from being outspoken or from writing a blog for The New York Times’s Chinese-language website. “I have no work unit, my parents have already passed away, and I have no children, and these are the biggest concerns that dissidents have when they express their opinions,” he says. “Relatively speaking, I have far fewer fears.”

More and more people are joining the so-called Reincarnation Party—bloggers who bounce back with new microblog accounts after existing ones are shut down. In some cases, a microblogger may have reincarnated himself hundreds of times in order to stay active on the Internet. “This has come to symbolize people’s resistance and struggle against censors,” says Yaxue Cao, a Washington-based China watcher and founder and editor of ChinaChange.org.

Others have not been as lucky. Charles Xue, whose blogger name was Xue Manzi, was an outspoken critic of the government on his microblog, which had 12 million followers. His blogging came to an end when Xue was arrested after allegedly being caught with a prostitute. Xue was soon paraded in front of national television audiences—despite not yet having gone to trial—to make a public confession in which he admitted he’d been irresponsible in his postings, a detail that had nothing to do with the alleged prostitution charges. The appearance of the now humble-looking Xue, wearing handcuffs and prison clothes, was taken as a warning to the Internet community.

In September, Beijing announced new measures to prevent the spread of what it called irresponsible rumors, including a three-year prison sentence if false posts were visited by 5,000 Internet users or reposted more than 500 times. Within weeks, dozens of Chinese were being investigated under the new rules, including a 16-year-old middle school student who was detained in Tianshui, Gansu province, for allegedly spreading rumors that the local police had failed to properly investigate a death.

The scare tactics are working. Murong Xuecun ticks off a long list of the names of prominent Chinese whose blogs have been shut down or who have been arrested, all in recent months. With such news spreading quickly he says that “even the dumbest person will reach the following conclusion: the situation is tense now, it’s better to shut up.” By the end of 2013, China’s Big Vs—influential verified microblog users, some of whom have millions of followers—had for the most part disappeared from the Internet as a result of this pressure.

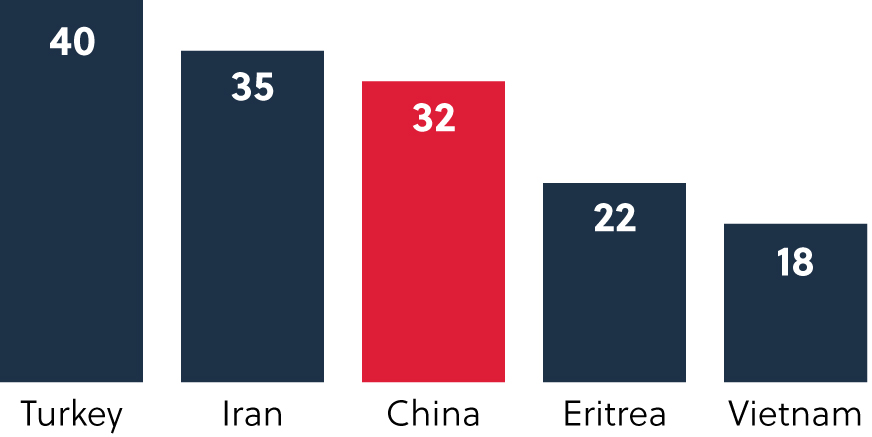

Chang Ping, former chief commentator and news director of Southern Weekly, a newspaper in Guangzhou, says that the domestic media is under tremendous pressure, explaining that until recently, newspapers that dared to report truthfully pulled in more advertising, and so were willing to take greater risks. “Now there’s no economic support but more pressure,” he says. The Committee to Protect Journalists reported in December that 32 Chinese journalists—which includes online commentators as well as mainstream journalists—were in prison, placing China No. 3 on the list of the worst nations for journalists in which to work.

Some of the country’s most prominent journalists and writers have now silenced themselves, and some have even left the country. China once had a blossoming corps of investigative journalists who did groundbreaking stories, but many of them gave up their profession under pressure, with some leaving journalism to turn to other careers. Also worrisome, in August, China’s Propaganda Department ordered all journalists at state-run media—some 300,000 reporters and editors—to attend Marxism classes. While there has been a similar program since 2003, the new requirement appears to be more rigorous, and is an example of the government’s determination to firmly control journalists at a time when social media is exploding.

China once had a blossoming corps of investigative journalists who did pioneering stories, but many of them gave up their profession under pressure

Meanwhile foreign journalists continue to face surveillance, harassment, intimidation, restrictions of their movements, and, in extreme cases, physical danger. In surveys conducted by the Foreign Correspondents Club of China, 94 percent of respondents in 2011 felt conditions had worsened over the previous year; in 2013 that number dropped to 70 percent.

Journalists with The New York Times and Bloomberg News who had applied for visas to work in China have been waiting more than a year for visas to move to China to work. The delays were seen as retaliation for New York Times reporter David Barboza’s Pulitzer Prize-winning report on the wealth obtained by the family of former Premier Wen Jiabao and Bloomberg’s investigation into the wealth of the relatives of President Xi Jinping. The New York Times website is blocked in China, as is Bloomberg’s, whose terminal sales in the country have fallen due to cancelations by government agencies.

On November 8, Journalists’ Day in China, I was informed that the Ministry of Foreign Affairs had rejected my application for a journalist visa to take up a position in Beijing with Reuters, ending an eight-month wait for a visa and an 18-year career as an accredited journalist in China. I was the second journalist in two years to be refused a visa. Al Jazeera reporter Melissa Chan was expelled from China in 2012, also believed due to her reporting on human rights.

Evan Osnos discusses Paul Mooney and Bloomberg

The Ministry gave no reason for my rejection, but during a 90-minute interview at the Chinese Consulate in San Francisco, I was questioned repeatedly about my views on human rights, the Dalai Lama and Tibet, and rights lawyers. At the end of the interview, the counselor officer said to me, “If we give you a visa to return to China, we hope your reporting will be more objective.” The experience made me realize that the visa refusal was the result of my reporting on sensitive issues.

That same week, The New York Times reported that Matthew Winkler, editor in chief of Bloomberg News, killed an investigative article about connections between one of China’s richest men and a senior Party official for fear of angering the government, which was already delaying the approval of visas for the news organization’s journalists wishing to come to China. Winkler denied the report, saying the story needed further work and was still under consideration. Michael Forsythe, the lead writer of the article, was fired a week later on suspicion of having leaked the news to the Times. Chang Ping says the lesson to the foreign media is clear: “Either you cooperate with them, or you get out of China.”

“I think the current huff in China’s leadership over visas for The New York Times and Bloomberg is happening to a large extent because the wall between foreign and domestic news coverage has begun to fall,” says David Bandurski, editor of the China Media Project at the University of Hong Kong. In today’s networked world of Facebook, Twitter, Sina Weibo, and WeChat, the distinctions between foreign and domestic news coverage are becoming blurred. “Translated versions of foreign news can be consumed domestically almost instantaneously,” he says. “The best solutions, from the standpoint of the Chinese leadership, may be the most old-fashioned ones: Cut the news off at its source, by making it impossible for foreign journalists to get close.”

Wen Yunchao, a Chinese activist who uses the name Bei Feng on the Internet and a former citizen journalist who now lives in New York, says that President Xi and his predecessor Hu Jintao have two different views of the Internet. “Hu saw the Internet as just a tool, and so advocated using it for the Party’s purposes,” says Wen. “Xi directly understands that the Internet and totalitarianism are incompatible, and a big disaster for the Party and the nation, and so he wants to control and clean up the Internet.”

Hu says further that Communist Party officials fear that China will experience a movement similar to the Arab Spring: “They worry that every single individual or mass incident could become the fluttering of a butterfly wing that could give rise to a windstorm. They’re afraid that the action of one citizen could be like that of the peddler in Tunisia who self-immolated.”

The country is facing an increasing number of protests by abused migrant workers, disgruntled factory workers, farmers who have lost their land, and even unhappy urban residents. Tibetan areas have seen some 127 people set fire to themselves to protest abusive Chinese policies in the region, and there has been an increase in the incidence of violence in Xinjiang, a Muslim area in far northwest China.

“Xi Jinping and Co. feel a pressure that they don’t know how to handle,” says Perry Link, an expert on China at the University of California, Riverside. “On the surface, China is ‘rising,’ getting stronger economically, militarily, and diplomatically, but internally it’s getting more hard to handle, because complaints and demands from below are increasing and are better organized than before.”

Citizen journalists using computers, mobile phones, inexpensive cameras, and video recorders are venturing into places the mainstream media fears to go. This new technology has eased the job of both foreign and local journalists, who now have many new sources of information, learning about stories from websites, microblogs and blogs. And sources can be reached more easily via e-mail, mobile phones, Skype, QQ instant messaging, and other modern tools.

According to Chinese journalist Anti, Xi is very confident about his power and doesn’t care about negative publicity. “He’s not even concerned about the reaction of Western countries,” he says. “These countries don’t react and so Xi is more confident about using his power. My conclusion is that the crackdown comes from confidence and not from fears.”

For Bandurski of the China Media Project, the fundamental problem is that China continues to consider information control as “an imperative in maintaining stability, when in fact information has become a more crucial part than ever before of the solution to the myriad problems facing China.” He points to the problems of local corruption, land grabs, property demolition, abuse of power, and perversion of justice. “When the media, even those that aren’t local, can’t report on these cases, and when they are scrubbed from social media, this creates an enormous undercurrent of pressure,” says Bandurski.

Chinese are also now getting information from a number of so-called citizen journalists who are able to report on news that the mainstream media has been unable to cover. A documentary released in 2012, titled “High Tech, Low Life,” introduced the work of the blogger Zhang Shihe, better known as Tiger Temple. In the video, Tiger Temple pedals his rickety bicycle, loaded with digital cameras, video recorders, and other high-tech equipment, from his home in Beijing and travels across China giving voiceless rural citizens a way to reach the outside world. He is saddened that during the space of just a few days between the end of April and the beginning of May his nine blog accounts were all shut down, including the longest-lasting one, which he worked on for 10 years, the one he and describes simply as “my pride.” He says he posted writing, photographs, video and even drawings on his microblog, unceasingly recording what was happening across the country.

The government may find it difficult to deal with the growing army of Chinese who don’t seem inclined to retreat. Murong Xuecun, for one, is optimistic. “I’m brimming with confidence for the future of the Internet as new technologies and new software are unceasingly emerging in large numbers, while the technology used by the Party to control and monitor the Internet will always lag slightly behind,” he says. “Furthermore, this regime established on a foundation of lies and violence will inevitably weaken, and even if there’s just a tiny bit of space, the peoples’ voices will be heard, making even more people wise. And more wiser people is the greatest threat to the Communist Party.”

The strong determination of Chinese citizens to overturn the controls imposed by the government can best be seen in the words that Murong Xuecun posted in the final week of December—sentences that lasted just a little more than 26 minutes before being deleted: “I will bounce back each time because my brothers have created dozens of new accounts for me. If these are not enough, we can create dozens more, and hundreds more. Let’s turn this into a battlefield, and fight it out. You point your gun at me and I stick out my chest. Let us brazenly attack each other. You abuse your power in the darkness, and you don’t stop for a single day. And I too will not give up for a single day, until one of us is dead.”

Paul Mooney is an American freelance journalist who reported on Asia for 28 years, the last 18 from Beijing. In 2013 he was denied a visa to report in China