Malone is a magazine writer, not an oral historian. But her working method for the Cosby story could have been pulled straight from the oral historian’s handbook. Ask open-ended questions. Get people talking, and keep them talking. The women, to Malone’s surprise, did just that. And the more they talked, filling 232 pages in transcripts, the more Malone realized her voice, the writer’s voice, would only get in the way. “The flow of a feature didn’t feel quite right for it,” she says. “To me, what was so effective was hearing from the women themselves and having that be as undiluted as possible.”

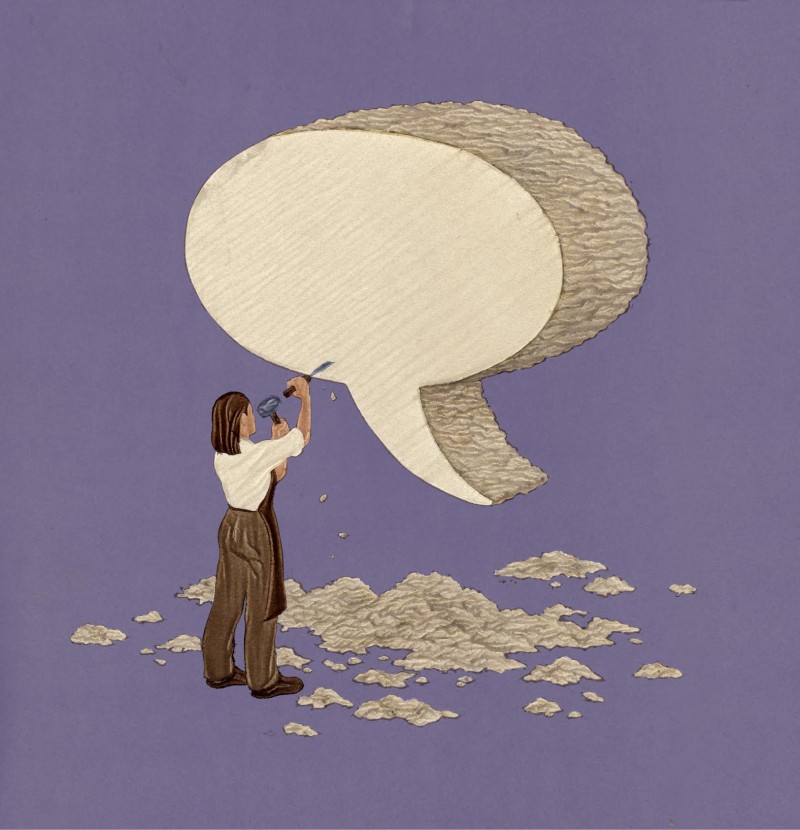

Her editors agreed. So Malone edited the transcripts down by theme: how the women met Cosby, what happened, and why they came forward. And the story that resulted was something of a hybrid. Malone wrote an opening essay, followed by first-person “testimony” from the alleged victims—an oral history, of sorts, like writing, only completely different. “It’s the opposite of writing,” Malone says. “You’re not taking a blank page and creating something new from it. You’re sculpting away; you’re chipping away; and cutting to make it so much better.”

Oral history is undergoing something of a revival. In recent months alone, magazines like Rolling Stone (oral history of the Allman Brothers), Vanity Fair (oral history of the Comedy Cellar), and Outside (oral history of “Hot Dog… The Movie”) have published panoramic tales using first-person interviews. Last year, Belarussian author Svetlana Alexievich won the Nobel Prize for Literature for her body of work, including “Voices from Chernobyl: The Oral History of a Nuclear Disaster,” a compilation of interviews, written as monologues, stretching at times for pages and detailing the horrors of the 1986 nuclear accident.

StoryCorps, perhaps more than any other organization, has helped make oral history mainstream. The project, which has recorded some 65,000 conversations since 2003, archiving them at the Library of Congress, specializes in recording first-person voices. Last year, the organization made it even easier for people to preserve their stories, launching a free mobile app that has since notched up nearly 80,000 interviews. And, in general, more people are listening, according to Robin Sparkman, the organization’s CEO: StoryCorps podcast listenership has doubled in the past year. “Human beings all over the planet, we’re really trying to connect to other people,” Sparkman says of the growing interest in oral history. “There really is a human need—a biological, emotional need—to connect with another person. And I think this is a way of doing that. It’s a form of intimacy, and it’s cathartic. It’s being heard and being listened to.”

Since it launched in 2003, StoryCorps has helped make oral history mainstream

Even archival material—recorded long ago and stored away, often forgotten, in academic libraries—is in greater demand, observes Doug Boyd, director of the Louie B. Nunn Center for Oral History at the University of Kentucky and president of the Oral History Association. “We used to brag about 500 people using our collection a year. We’re getting about eight to ten thousand a month now,” he says. “We get requests, every day, from all over the world.” And he’s getting new material, too—new interviews—five times what he used to collect in a year.

“Everyone’s speaking for themselves more,” says journalist and documentary film producer Clara Bingham from her book-lined office on New York’s Upper West Side. “Everyone’s blogging. And there’s less tolerance in having the editorial buffer of an editor, journalist, writer. People are gravitating now to first-person story voices more than they have in a long time. It just feels like we’re in a first-person storytelling renaissance.”

With “Witness to the Revolution: Radicals, Resisters, Vets, Hippies, and the Year America Lost its Mind and Found its Soul,” which hits shelves later in May, Bingham is part of that renaissance. Long interested in oral history, Bingham decided to do the book—the story of the turbulent times from 1969 to 1970, told through the voices of the peaceniks, protesters, and others who lived them—in the form. But by the fall of 2012, her initial excitement was spiraling into doubt. “I had a bunch of dud interviews,” she recalls, “where people didn’t remember anything.” Other key protagonists were long dead or unwilling to speak at the level of detail Bingham needed to carry the narrative in their voices. She had begun the project thinking it would be simpler than penning a traditional nonfiction narrative. Now, she was thinking something else: It would be so much easier to just write the book.

“I was just really struggling with this new form,” she says. “If you’re writing a straight history—if you’re Rick Perlstein writing about Nixon in ‘Nixonland’—I could use anything. I could use all of those documents. I could use all of the first-person and all of the histories, and weave it all in to tell the story. Instead, I had my hands tied because I needed to stick to the first-person voice.”

That fall, over coffee at a midtown diner in New York City, Bingham met with her editor, Jon Meacham, winner of the Pulitzer Prize and the best-selling author of biographies of Andrew Jackson, Thomas Jefferson, and others. And unlike Bingham, he wasn’t concerned. “I remember he said, ‘You know, this is your book. There are no rules. You can do whatever you want to do.’ And the second I decided I could do whatever I wanted to do, that really freed me up.”

Where Bingham struggled to get her characters to speak—on the record, to her—about their pasts, she plugged holes, borrowing tracts from the characters’ diaries and memoirs. The decision kept her 656-page book in the first-person and revealed something else about oral history as a form: The rules are fungible. Journalists pursuing oral history narratives employ different strategies and techniques to tell their stories. But it’s also clear—through a growing raft of magazine articles, radio pieces, and books—that reporters, interested in narrative, are increasingly turning to oral history as a vehicle for storytelling.

The term, oral history, has been around for decades, though, early on, it was primarily the domain of folklorists, archivists, and academics. In the 1930s, the Federal Writer’s Project, funded by the New Deal, gathered the first-person narratives of former slaves, still alive in America; people who had traveled West in covered wagons; and others with interesting stories, say, about meeting Billy the Kid or surviving the Great Chicago Fire of 1871.

But it wasn’t until 1948 that oral history became an area of true academic study. Allan Nevins, a Pulitzer Prize-winning author and historian formed an oral history department, the nation’s first, at Columbia University. Nevins was worried about changes in the world—namely, the growing popularity of the telephone and the declining number of people keeping diaries—and how those changes might hurt future generations trying to tell stories about the past. “There was this fear that historians in the future were not going to have enough evidence in the archives to write the history of the contemporary moment,” says Sady Sullivan, current curator at the Columbia Center for Oral History Archives.

So Nevins set out to conduct an experiment: He’d gather “oral autobiographies” of important policy makers who might later interest historians, transcribe the interviews and make them available to all. Like a memoir, Sullivan says, “It was meant to be read.”

Few publications have pursued oral history as often—and as in-depth—as Vanity Fair

But by the 1960s and ‘70s, people interested in oral history were increasingly focused on gathering sound, and then using that sound—the interviews they had done—to build something all its own. The dawn of the portable stereo tape recorder made it an increasingly affordable endeavor. Great journalists, including Studs Terkel and George Plimpton, began to play around with the form, inventing something new. “A relatively new genre in publishing,” Plimpton wrote at the time, “the use of oral history as a form of communication.”

Some early guidelines, penned by longtime oral historian Willa Baum, in her book “Oral History for the Local Historical Society,” included tips that remain relevant even now: “An interview is not a dialogue … Ask one question at a time … Ask brief questions … Don’t let periods of silence fluster you … Try to avoid ‘off-the-record’ information … Don’t switch the recorder off and on … Don’t use the interview to show off your knowledge, vocabulary, charm or other abilities.”

Bingham realized early on how important those tips were. “I had to be a much better interviewer,” she says. “I couldn’t do any backfill. There was nothing I was able to add. I needed each one of my characters to tell their entire story. So it was a much more elaborate, intimate, involved interview—especially with the main characters—than it would be in a normal sort of history.”

Bingham began by coaching her subjects. “I need you to be really basic in describing everything,” she recalls telling them over and over again. No acronyms. No jargon. “Don’t assume I know anything,” she’d say, before asking her sources to walk her through the shootings at Kent State University, or the My Lai massacre, or the bombing campaign in Cambodia. “You need the person to introduce themselves and even talk about the most obvious things,” Bingham says. “Very basic stuff that I could have found out, but I needed them to say it.”

Often, they didn’t—not intentionally, Bingham says, but because they went off on a tangent or didn’t understand what she wanted. So she’d stop the interview and go back. “All the time,” she said. “I’d circle back, circle back, circle back. And if I couldn’t get the right answer, I’d ask it three different ways.”

It’s a problem every reporter faces, but one that’s especially tricky when the writer is limited to using only the interview. That’s why those who pursue the craft on a more regular basis are almost scientific in their approach. “When you’re putting together an oral history, you’re part writer, you’re part reporter, and you’re part editor—all at the same time,” says Cullen Murphy, editor at large at Vanity Fair. “And, if you’re lucky, you’re also working with a team of people who are in the enterprise with you. You’re calling up one another and saying, ‘Hey, I just spoke with so-and-so. Listen to this.’”

Few publications have pursued oral history as often—and as in-depth—as Vanity Fair. Since 2000, the magazine has published lengthy oral histories on “The Simpsons,” Guantánamo, and the birth of the Internet, among other topics, building them out of detailed interviews and writing them in the voices of the characters themselves. “In a way, it allows you to have your cake and eat it, too,” says Murphy, who has helped edit some of the oral histories and co-written one himself, “Farewell to All That: An Oral History of the Bush White House,” with Todd S. Purdum in 2009. “It allows you to bring a wide variety of voices into a story and really let them have their say, while, at the same time—because you’re exercising editorial judgment and also you’re shaping the material—you have a certain type of control over it.”The best ideas, according to Murphy, begin with a timeline: “It’s just essential. And once you have that, you have a horizontal bar running from start to finish.” The Vanity Fair team working on the story then identifies key points on that horizontal bar and makes a list of important players. “And when you’re done with that, you basically have your game plan. You know who you want to reach. You know what you want to talk about. And, with the team of people, you begin doing it.”

In the interviews that follow, Murphy is not looking for an intense back-and-forth, but rather a conversation focused on stories, and assessments, and memories—of both the character’s behavior and the behavior of others. “You want the person you’re speaking with to just talk and talk and talk,” he says. “From time to time, you interject a question to focus it or bring up something they’ve said. But it’s deceptively passive. Because what you really want is for them to go on as much as possible.”

For the Bush White House story, Vanity Fair spoke to about 50 people, generating some 2,000 pages in transcripts. Then it’s the editor’s job to begin asking questions: When am I learning something new? When am I getting a take on a situation that seems fresh? The best oral histories aren’t just a walk down memory lane, but a journey into something new and hopefully revealing, moments people have never discussed before.

Svetlana Alexievich's "Voices from Chernobyl: The Oral History of a Nuclear Disaster" details the horrors of the 1986 nuclear accident through a compilation of interviews written as monologues. Alexievich won a 2015 Nobel Prize for Literature for her body of work

At that point, the timeline developed by the editors helps inform where the material will be placed in the narrative. But for journalist and author James Andrew Miller, it’s important that reporters be flexible when working with oral history interviews. “I’ve never been a slave to any kind of outline that I’ve done,” he says. “You have to be prepared for all these delicious surprises that come up. Otherwise, you’re basically driving a Porsche at 40 mph. If you’re not going to let yourself be swayed and moved and affected by what you’re learning in these interviews, then it’s pointless.”

Miller is the co-author of two previous oral history narratives: “Live From New York,” the behind-the-scenes story of Saturday Night Live, and “Those Guys Have All the Fun,” about the rise of ESPN. This summer, Miller will publish his latest: “Powerhouse: The Untold Story of Hollywood’s Creative Artists Agency,” one of Hollywood’s great power brokers, involving more than 425 interviews, many with people who’d never before spoken with a journalist.

Often Miller’s biggest challenge is getting sources to go on the record, because, without the material, in their words, he can’t use it at all—and with “Powerhouse,” he says, that was certainly a problem he had to overcome. In the final stages of editing the new book last winter, Miller flew to Los Angeles to have meetings with nearly two dozen people, trying to convince them to put certain anecdotes on the record. “I pleaded and begged and tried to explain why I thought it was important,” he says. In the end, there was no convincing some people. Still, oral history remains Miller’s favorite vehicle for telling stories: “There’s just nothing more revealing. The level of verisimilitude is much higher. The rawness is more apparent.”

The best oral histories aren’t just a walk down memory lane, but a journey into something new and hopefully revealing

Noreen Malone, at New York magazine, doesn’t always think so. “I actually don’t always love oral history as a form,” she says. She worries, at times, that oral histories can be lazy, an indication that the reporter couldn’t figure out how to write the story and dumped the interview transcripts onto the page instead. But there’s no question that the form is popular, not only among editors, but among readers. And there are numbers to prove it.

In 2009, New York magazine’s oral history feature “My First New York”—with famous people recalling their first weeks in the city—drew more than a quarter of a million page views and a book deal. Four years later, the magazine commissioned another feature dubbed “Childhood in New York,” with still more famous people telling stories, in the first person, about growing up in the city. Again, the piece resonated, generating nearly 700,000 page views, according to the magazine’s internal statistics. And then came the Cosby cover story. The initial tweet, with the cover photo of Cosby’s 35 alleged victims and Malone’s story attached, racked up more than 13,000 retweets and four million impressions. At the newsstand, the print edition with the Cosby story was New York’s top seller for 2015. And online, the Cosby piece was also tops—by both unique visitors, with some 1.7 million in all, and time spent—across all the magazine’s digital platforms.

There was news value to the story, of course, and powerful photos of the women to go along with it. Both elements certainly helped the piece have an impact, well beyond New York City, the magazine’s subscribers, and readers already interested in the broadening Cosby scandal. But editors at the magazine believe the oral history approach helped, too. For the first time, really, people got to hear from the women themselves—all of them together—and there was power in that, according to Malone. Back at her desk in New York, she prepared herself for a backlash—from critics, Cosby supporters, and Internet trolls. “But the response,” Malone says, “was overwhelmingly in support of these women.” Readers had heard their voices.