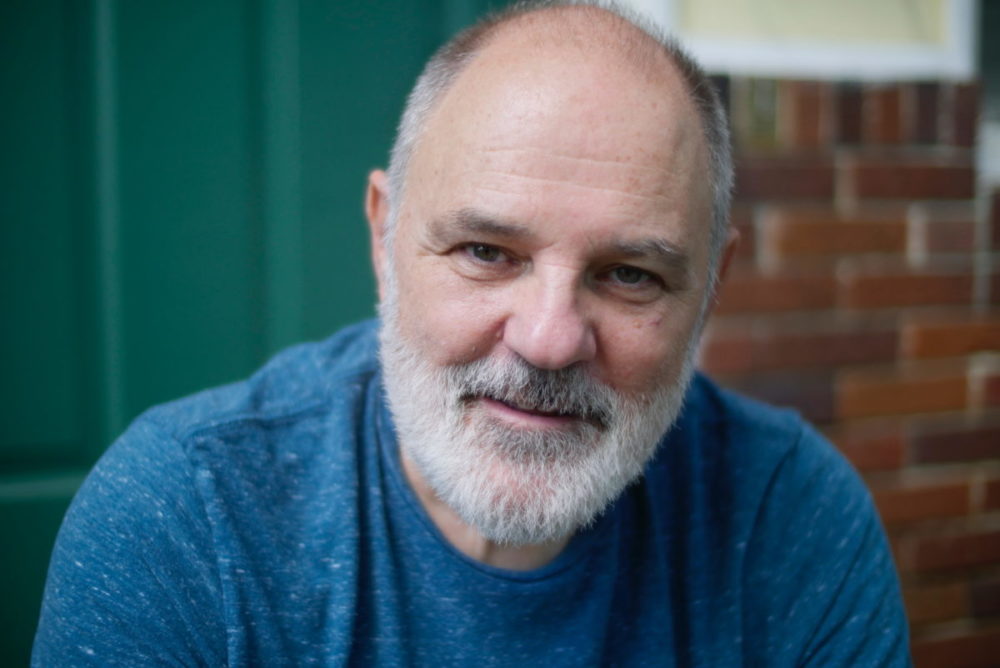

The atmosphere at Elmhurst Hospital in Queens, New York on April 16, 2020.

In “The Epicenter,” an urgent narrative from the heart of the pandemic early in its explosion, a team from The New York Times sought to remedy that gap in coverage, and dared to get close. To do so, they trained their sights on a “pinpoint on the map” of the New York City borough of Queens, as COVID settled in last March. That’s where five interlocking neighborhoods, a melting pot of immigrants, became ”the global epicenter of the kind of health crisis not seen in the United States in a century,” as described by lead writer Dan Barry. The bold set-up to the story:

As winter turned to spring, the coronavirus hit a corner of Queens harder than almost anywhere else in the United States.

Thousands became ill. Hundreds died. And a nation was put on alert.

That alert remained on high — and too often unheeded — until early December, when the project was published. As of this posting, the number of COVID cases in the U.S. reached 21.5 million, with 365,000 deaths. Worldwide, cases topped 86 million with nearly 1.9 million deaths. The hope offered by the release of several promising vaccines likely will take months to be realized. It’s a story that shows no sign of becoming yesterday’s news.

An enormous story told through a small frame

The story idea was born in in mid-April, when Barry said he and Metro editor Cliff Levy “were trying to figure out how to capture the enormity of what was occurring.” Wave after wave of relentless news — the pandemic, the presidential campaign, racial justice demands and more — left newsrooms little time to process one event before another swept in. The solution was inspired by a journalistic classic:

“We decided to attempt a John Hersey ‘Hiroshima’-like story that drilled down on New York City’s worst moments, in late March and early April, and centered on Elmhurst Hospital and the surrounding neighborhoods,” said Barry, a Pulitzer Prize winner and one of the finest stylists in journalism.

The paper assembled its team: Barry, immigration reporter Annie Correal and photojournalist Todd Heisler, who both speak Spanish, and freelance reporter Jo Corona. The team was led by editor Kirsten Danis, who had a reputation for rigor and care with language, and set to work on what would become an eight-month project. “There is always value in going back,” Barry said. The reporting — as relentless as it was creative — relied on social media, research, shoe leather, diverse collaboration, powerful prose and a passion for revision that, at 11,450 words, reads like a taut tour de force.

The story focuses on a compelling cast of characters in a micro-world where some 800 languages echo among the immigrants who flock to the city for a slice of the American dream:

A big-hearted Mexican performer. A nurturing Thai chef and his grieving partner. A Bangladeshi taxi driver and his devoted daughter who leaves her Ivy League college to watch over her parents. An emergency room doctor at a hospital inundated with patients. A mortician who shuttles back and forth with bodies. A police commander worried about his officers and the communities they protect. An immigrant from Ecuador living in a cramped apartment with 11 family members, including her elderly parents. A frightened Nepalese Uber driver who fled a restricted life as a Buddhist monk and made his way to this country.

It follows each from the moment of a first worrisome cough or sudden collapse that sends them in screaming ambulances to Elmhurst Hospital, a venerable institution where frantic medical professionals try to keep up. Patients wait for hours in emergency rooms until a bed becomes free, or lie in hallways crowded with the sick and dying. Some will live. Others will die.

It is told in an omniscient voice; minimal attribution relies on the readers’ trust. Reconstruction bears witness in granular detail to an array suffering by patients and their loved ones. Narrative digression is used to introduce and track the movements of multiple characters. The writers juggle the lives of all these characters by first teasing bits of information to readers and then spotlighting each until they become fully formed and indelible. The calendar serves as an organizing principle to follow the different life threads, while time-stamped quotes from President Trump and other officials offer a jarring counterpoint to the misery playing out in Queens — a misery being echoed across the nation and around the world.

We reached out to Barry and Correal to ask about the work that went into a challenging and compelling piece. Their answers were sent back by Barry, who also helped us annotate the published narrative.

How did you find the characters in your story and track their progress at the height of the epidemic in Queens?

Annie Correal and I, along with Jo Corona, a freelance reporter who worked very closely with us, cast a wide net. We reached out to local council members, religious leaders, community advocates and others to find possible characters to focus on. We knew that what we wanted was a situation in which the reader became invested in individual lives, and would not know beforehand whether those characters survived. So we also looked at GoFundMe and Facebook pages and other social media that reflected memorials, or hinted at someone who knew someone who had been sick. In addition to that, Jo spent a lot of time walking the neighborhoods, chatting people up, listening for leads.

How did you choose your primary subjects?

We needed these characters to have gone through something in a roughly defined time period, and to have lived or worked in a defined, eight-square-mile patch of Queens, with the No. 7 subway line and Roosevelt Avenue below it serving as a rough spine. We also needed to convey the breathtaking diversity of these communities. For example, we could have done an epic just on Bangladeshi taxi and Uber drivers. But we wanted men and women, young and old, of several races to convey the virus’s indiscriminate nature.

As we went along, gathering names and back stories, some people who initially seemed like major characters became secondary figures, while some secondary figures rose to prominence — all based on an alchemy of representation, life and death.

How did persuade your characters to reveal the most intimate details of what they went through?

Mostly we listened. Then, once we found our subjects, we won their trust by signaling that our interviews were not one-and-done — that we would be back, both personally and remotely, to listen to their stories. I know from experience that when a subject senses that you are in for the long haul, and determined to get their story right, they are more willing to share their stories. To entrust their stories to you.

The reporting focuses on events that take place nine months before publication, at a time when media access to victims and hospitals was extremely limited. How did you work through that?

The story is almost entirely a reconstruction, although we did a lot of rigorous fact-checking and many repeated interviews. For example, Joe Farris, the partner of the Thai chef Jack Wongserat, provided text messages that allowed us to pinpoint certain events and to confirm Joe’s recollections about Jack’s concerns. Our commitment was to be factual and true.

With a few exceptions, the narrative is told in an omniscient, you-are-there voice, without attribution to help readers understand the sources of often intimate information or the research methods employed. What led to that approach?

We were attempting to produce a piece of narrative nonfiction. With that, I think, comes a heightened attention to language, to structure, to pacing — all the elements you would hope to find in a short story. Repeated attributions throughout an 11,000-plus-word piece would break the spell being created, taking the reader out of the moment.

True, we are implicitly asking the reader to trust that what we are writing is factual. But this didn’t bother us because we knew what we wrote was factual and true. We knew this because we talked repeatedly to the living subjects, as well as to many other people who are not mentioned by name in the piece. Beyond that, there was all the other research, including the daily reporting from the time by The New York Times and other outlets.

You share a byline with Annie Correal, who covers immigrant communities. How did your collaboration work with her and the others on the team?

I don’t want to speak for Annie, but I would say it was seamless. She has a bottomless curiosity about immigrant communities and New York City, speaks fluent Spanish, is a compassionate, gifted writer, and an exacting reporter who understands the importance of detail and small moments.

I’m older than her by a couple of millennia, but I learned something from Annie just about every day.

Of course, we both had to navigate around the coronavirus. We never met in person; we only met on Zoom — about 1,000 times. And the way we divided up responsibilities seemed pretty organic. At the end of the day, she focused on the story of Yimel Alvarado, the Mexican entertainer; the Lema family from Ecuador; and the Chowdhury family from Bangladesh. I focused on Jack, the Thai chef, and his partner, Joe; Dawa Sherpa, the Uber driver; and Dr. Laura Lavicoli and Elmhurst Hospital.

We then worked together to develop the chronological structure, on what to keep and what to cut, which scenes are too long and which don’t say enough.

We also greatly benefited from the work of the freelancer Jo Corona, who made initial contact with some of the characters — Joe, the partner of Jack, for example, and the people at the Guida Funeral home — and spent many hours walking the streets, looking for characters and tidbits. There is a short reference to a man offering the use of his truck to his church congregation, for example. Jo knew the man’s entire story, and it was an epic in its own right.

The photographer, Todd Heisler, was, as usual, an exceptional reporter with an unerring eye for the telling detail. He and I have worked a lot together in the past (“This Land” columns, “The Case of Jane Doe Ponytail”) and we have our own rhythms. He and I were together at the hospital and at the funeral home. He was also with Annie for the memorial service for Yimel outside the El Trio restaurant and bar. Those images are exceptional and helped in the writing of that scene.

What about the writing itself? Whose hands were on the keyboard?

The writing was collaborative. Annie would write her scenes, and then I would synthesize them into what I was writing, always conscious of preserving her language and sensibility. I probably had my hands on the keyboard more, in part so that the narrative would have that unified, omniscient voice. But along with editors Kirsten Danis and editor Lanie Shapiro, Annie and I went over every word and punctuation mark. This is not hyperbole.

The editors contributed in so many ways that there’s too many to recall. Cliff Levy, the Metro editor, understood the concept immediately, provided the necessary time and resources, made strong suggestions about the narrative, and then championed the hell out of it. Lanie Shapiro, a senior staff editor for the Investigations desk, elevated the project with her close read, her copy editing, and her counsel. And Annie and I can’t say enough about Kirsten Danis, the investigations editor for the Metro desk. She lived and breathed every development and failure, was not shy in signaling when descriptions went on too long or language was too purplish, encouraged us when encouragement was sorely needed, and then worked overtime to get the graphics, photography, print, and social media teams on board.

***

The annotation: Storyboard’s questions are in red; Barry’s responses in blue. To read the story without annotations, click the gray quote boxes throughout the story.

THE EPICENTER

By Dan Barry and Annie Correal

Photographs by Todd Heisler

The New York Times

Dec. 3, 2020

She wears a red wig and a black dress she sewed herself. It hugs her body as she moves about the stage, lip-syncing love songs in Spanish to a room filled mostly with absence. What a vivid opening for a heartbreaking story, describing someone singing “to a room filled with absence.” Why did you allude rather than spell out the pandemic? I think that by opening with Yimel Alvarado performing in a mostly empty nightclub on a Monday night in early March, we were laying the groundwork of foreboding. It is clear from the headline that this story was about the pandemic. But we wanted to recall the moment just before that reality struck — to set the mood of life unfolding naturally in an unnatural time. So many other COVID stories had begun with a hospital scene, or a scene of illness, and we anticipated that such scenes would be exit ramps for fatigued readers. We also wanted to begin at some point right before the numbers surged, and this event presented itself. It had built-in drama and a sense of place. There is also something resilient — even defiant — in Yimel singing through this moment: a determination to push through. And when we learned that one of the songs she was singing included the lyric “It is too late,” I knew that this section had to end on that line. Was a reporter on hand to witness this scene as it happened? No. This took place on March 9, more than a month before we began this project. We learned about Yimel Alvarado in the late spring from an organizer at Make the Road New York, a local community organization of which she had been a member. The organizer put us in touch with the owner of the El Trio restaurant, a fellow performer and close friend of Yimel’s. She invited Annie (Correal) to come to her empty, closed bar for an interview in late June. From there, Annie learned about Yimel’s last performance, took notes on the look and feel of the performance space, and developed relationships with Yimel’s family and friends, who were present on March 9 and helped to recreate the night. We also had many photos and videos of Yimel performing on other occasions.It is late on March 9, and Yimel Alvarado is at her regular Monday gig, a nightclub above a Mexican restaurant in the Corona section of Queens. This is where she feels at home, where the usually robust crowds of gay and transgender patrons applaud her teasing banter. How were you able to pinpoint the date? Yimel had a weekly Monday performance at El Trio that she called “Noches de Cabaret.” We knew the date from her Facebook posts, and from the recollections of the bar owner and her friends. It was, of course, her last performance.

Drink up, she often says, as fans toss money at her feet. The night is getting away. “Often says” implies that this is her custom. Is that the point, something that came up in the reporting? We were told by her friends that this was part of her routine; she would lip-sync songs and play emcee as others performed. Between numbers, she would goad the crowd and tell little jokes. This was one of the motifs of that routine. What does putting her quote in italics, rather than quotations marks, signify? It’s an approach taken several times in the story? Why? Do you think readers will understand the decision? We don’t have transcriptions of the night. The best we have are the recollections of the participants. Since quotation marks are sacrosanct, another way to convey conversation in a reconstructed moment is to use italics. It’s been used before, in Frank McCourt’s memoir “Angela’s Ashes,” for example. I think the italicized words both keep the reader in the moment and signals to them that this is the best approximation we have of what was said, based on the recollections of others.

But Yimel is not herself tonight; hasn’t been for days. Her Cleopatra-like eyeliner only accentuates the exhaustion in her gaze. Just a cold, she says.

At some point, the concerned bar owner reaches for the tequila. The two friends knock back shots while, nearby, a few spare patrons kiss and huddle for cellphone selfies. Who’s the source for this scene? Why not identify the bar owner? The source is the bar owner. We decided not to name her as we wanted this first scene to move quickly, create an atmosphere, and not be weighed down by several names. In addition, the bar owner doesn’t reappear in the piece — though at the memorial in July she performed a memorable lip-synced rendition of “A Mi Manera,” the Spanish version of “My Way,” in a black sequined costume. Why of all the major characters in the story did you decide to open with Yimel’s story? For many reasons. Her story allowed us to begin the narrative on March 9, when New York City was in the midst of mixed signals about the virus, and her memorial service took place in July, which seemed like a perfect moment for an epilogue — a pause after the deluge. So there was a bookend appeal. More than that, we also struck by the power and poignancy of Yimel’s story, and felt it represented many of the marginalized communities that have been disproportionately affected by the pandemic but whose stories had not been told. She seemed both larger than life, and so human.

The same denial and dread hover over the densely populated neighborhoods beyond the restaurant’s door, inside apartments subdivided by drywall and need, up and down the bustle of Roosevelt Avenue. The link is to a powerful visual story about the residents of illegal and often unsafe apartments in the basements of homes that blanket Queens. “Drywall and need” sum up underground dwellers’ plight with the compression of poetry. I often think of newspaper journalism and poetry united in the pursuit of deriving the most imagery and impact from the fewest number of words. This sounds precious, but each word has to earn its place. So the poetic voices in my head include Seamus Heaney and Mary Oliver and Galway Kinnell and Emily Dickinson and Billy Collins on and on. But in writing about New York City, I also hear writers who can zoom in on the particular and then zoom out for the Godlike view, as if we were all sitting beside James Stewart, mesmerized by the goings-ons of his neighbors in “Rear Window,” trying to make sense of it all. Anyone who writes about New York City wants, ultimately, to be E.B. White writing “Here is New York.”

In one building, an immigrant from Ecuador worries about the many relatives living in her cramped apartment, including her frail parents. A family member, her brother-in-law, has a persistent cough.

In another, a couple from Bangladesh gets a call from their daughter in her Ivy League dorm, who warns that they risk illness by going to work and sharing close air with strangers — her mother at La Guardia Airport, her father in his yellow cab. She begs them to stay home. They do not.

But an Uber driver is so haunted by the coughing of two recent passengers that he has stopped picking up fares. Thirty years ago in Nepal, he fled his life as a Buddhist monk, tossing his red robe under a tree. Now he prays as he disinfects his black Toyota.

Around the corner, a Thai chef who commutes by subway to Manhattan has been sending worried texts from work to his less-concerned partner at home. He frets about the growing number of confirmed cases in the United States.

Writing coach Jack Hart used the term “gallery lead” to describe story openings that illustrate that the same thing is happening in a variety of settings. Many stories begin this way when more than one character is featured. Why did you decide to wait until now? We didn’t want to overwhelm the reader. To begin a story with several characters can be confusing and can dilute the impact of each of those story arcs. By choosing one character, Yimel, in the lede, we hoped to draw the reader in first, rather than bombard them at the get-go with too much information and variety. And why didn’t you identify them by name as you did with Yimel Alvarado? We wanted to avoid what is called “character soup.” We hoped that the reader would be invested in Yimel, and would be intrigued by the promise of other stories to come.Is it here? The deadly coronavirus? Why use questions here? To convey the uncertainty at that time. Nearly everyone had heard of the coronavirus and yet there still existed a kind of disbelief. The questions are meant to convey that lingering disbelief.

At Elmhurst Hospital a short walk away, an emergency-room doctor has noticed a surge of patients with flu-like symptoms. Now there is confirmation of what she and her colleagues knew was inevitable: the hospital’s first case of Covid-19, the life-threatening illness caused by the coronavirus. We meet another character and, though she is not named, have begun to understand that she and others play major roles in the narrative. What’s your intent here? Just a continuation of signaling to the reader that more personal journeys will unfold, including a representative one inside Elmhurst Hospital, where the life-and-death dramas are playing out.

It is here. Three words that answer the question above. Why did you feel the need to make a declarative statement. Was it a question of pacing, impact? It was a call-and-response thought that indicated the suspense was not in whether the virus would come, but rather in how it affected real lives. We wanted a pause and a declaration, allowing the reader to stop and take that in.

But messages conflict. Gov. Andrew M. Cuomo has declared a state of emergency, while President Trump continues to downplay the virus. A “containment area” is about to be established in the small city of New Rochelle, while a dozen miles south the hurried hustle of Manhattan flows uninterrupted.

Soon, this pinpoint on the map of Queens, where so many cultures converge, will become the global epicenter of the kind of health crisis not seen in the United States in a century. Very soon.

This strikes me as a nut section that sums up the story with dramatic information that will grab readers. We needed to slip in a nut graph that did not disrupt the mood we were trying to create — facts of the moment that grounded the scene in real-time reality, and also underscored the earlier sense of disbelief. Why set apart “very soon” as a separate sentence?It was rhythmic, sounded right in my ear — a kind of confirmation of the imminent crisis that also adds to the building dread.For now, the weary-eyed Yimel Alvarado continues her performance, fortified by little more than the dose of tequila. Determined but unwell, she mouths a ballad in which a woman addresses the wife of her lover.

Ahora es tarde, señora

Ahora es tarde, señora

Too late now, señora.

More foreshadowing, the fateful kind. How did you find and select this particular verse from Yimel’s repertoire? Who translated it? It comes from one of the songs that Yimel was said to have sung that night — “Señora,” a ballad by the Spanish singer Rocío Jurado. It has been performed by many of the great divas of the Spanish-speaking world who Yimel would study, recreating their outfits and hairstyles and impersonating their gestures. In this context, the sad, rueful lyrics carry an ominous ring. Annie translated the lyrics, choosing the more colloquial “too late now,” to match the phrase in Spanish.***

Just about two miles separate the 69th and 103rd Street stops on the 7 train in northern Queens. Yet beneath its elevated tracks sprawls the world. This is another evocative paragraph that could easily lead a story. It balances the concrete with the abstract in such a powerful way. Could you talk about how you crafted it and why you decided to start the section this way? We needed to take a step back and ground our story in its extraordinary setting. We knew that this stretch of the 7 train would have served all of our characters. We also needed a jumping-off point to, quite frankly, marvel at this breathtakingly diverse corner of the world. By using the 7 train almost as a ruler on a map, we were able to set our boundaries between its 69th Street and 103rd Street stops.Within this span are five neighborhoods in the Queens jigsaw — Woodside, Elmhurst, East Elmhurst, Jackson Heights and Corona — whose combined histories reflect the evolution of New York: the Dutch and English settlements and the fields of wheat and corn, the railroad lines and the sprouting developments, the garden apartments for white Protestants only and the ash heaps immortalized in “The Great Gatsby.” Then housing for the masses, the faces ever changing. What research went into this graf? I spent an inordinate amount of time digging into the Times archives about this part of the city. I can tell you about the building of the apartments, the discriminatory rental practices of the early years, the disputes about integrating the schools. The bus terminal in Jackson Heights is named after the actor/comedian Victor Moore; I now know a lot about Victor Moore, and would have loved to have included his name, but we have to kill our darlings. I also spoke to several historians, and consulted various reference works about the history of Queens. Lastly, I was born in Jackson Heights/Elmhurst, so I was especially motivated.

To walk down Roosevelt Avenue now is to journey from the Himalayan peaks to the arid Mexican plains, to hear the music of intermingled languages and dialects, all within three dozen short blocks.

In the perpetual dusk cast by the subway tracks above, vendors sell woven baskets from Ecuador and leather sandals from Mexico, while Indian grocers display their produce and men carry skinned goats to halal butchers. Dentists and doctors offer their services from narrow storefronts, as do self-proclaimed healers, the curanderos, found among the statues and candles in religious-goods stores, available for counsel.

Did you walk the streets to be able to convey the special quality of this section of Queens? Yes, Annie and I walked Roosevelt Avenue and the surrounding streets many times, taking notes. The examples were carefully chosen. We wanted to include visual imagery, sounds and smells (conjured by the examples of the food.) This doubles as a way to communicate a rich mix of cultures and to signal authenticity. It is not just “music,” but cumbia and reggaeton; not just “tacos,” but the tacos of southern Mexico. Getting these things right was important; we wanted the piece to ring true for the residents of this area, not only to create an atmosphere for faraway readers.The lively rhythms of the street follow the percussive beat of cumbia, the thump of reggaeton, the call to prayer. Fueling it all is an international buffet of the sizzling meat tacos of southern Mexico, the steamed dumplings of Nepal, the Indian curries, the Peruvian ceviche, the Colombian buñuelos. As with so much of your writing and this story in particular, the specificity of detail and understanding convey such a voice of authority that attribution would seem superfluous. Where does that voice come from? I don’t know exactly. I suppose it rises only after the research has been done and the visits have been made. I tend to write down everything I see. Then, when it is time to write, I may use only a small fraction of the details in my notebook, but writing them down makes me feel as if I now own them, and can write with confidence. Even then, one can be overconfident, and the writer and the editor need to gut-check everything for fact and purpose.

And everywhere, people. Many work the service jobs that animate the city: driving, cleaning, cooking, building — up at first light to line the subway platforms, hard hats and coffee cups in hand. Many are distrustful of authorities, or vulnerable to exploitation, or simply too afraid to call in sick.

By the tens of thousands, they spill from brick tenements with narrow courtyards, from small houses with grapevine gardens, from basement quarters with little natural light. If lucky, they live with family or friends; if not, they live among strangers, paying for a bed or maybe just a couch.

Imperfect conditions for social distancing. Perfect for contagion. The contrast between the two tight sentence fragments, following the movement of the preceding dense-packed paragraphs, couldn’t be more stark or suspenseful. These two sentences were honed and revised, so that they would be clean, simple and, hopefully, like a punch in the nose. They were meant to raise the tension a notch, but also to explain why we had just given you a brief socio-demographic history of the area.

Saturday, March 14

‘This virus has spread much more than we know.’

— GOV. ANDREW M. CUOMO OF NEW YORK

Tell us about using the calendar as an organizing principle. It helped to ground the reader into a specific time, separated the scenes, and created a ‘tick-tock’ sense of urgency of things getting worse (before they got better.) It was also true to the time: Every day, practically, major events were taking place, case numbers were rising. More people were dying. A week was an eternity, given all the life-and-death struggles happening at the same time. We wanted to recreate that sense. And what about the quotes from city and state officials as subheads? We debated whether to use these quotations at all, and then we debated which ones were in best service to the story. They were meant as a sort of cinematic zoom-out, or voiceover, reminding readers of the larger picture, as well as of the officials involved, such as Governor Cuomo. The sense of urgency, awe, sadness, or, occasionally, false reassurance, in these quotations also said something about the time.Yimel Alvarado lies sick in the gloom of her tiny bedroom, a crucifix on the wall above her head. Pink satin curtains are drawn against the late-afternoon light, five days after her cabaret performance in the upstairs lounge at El Trio restaurant. “In the gloom of her tiny bedroom” is another slice of poetry. Could you talk about the source and purpose of this paragraph. Annie visited the room and interviewed Yimel’s sister and others about this moment. We also had photographs of Yimel in her bedroom from an earlier time.Whenever possible, we wanted to escort readers into the spaces where people were living in these neighborhoods, where the high rents create cramped and overcrowded conditions. These conditions are often cited as a central reason why Covid spread so rapidly in this particular slice of Queens. We wanted to capture a small room in one home, and to remind the reader that Yimel is the performer from the first scene. Details like the crucifix and the curtains are meant to transmit information about who she is; what she cares about and believes in.

Since then, a low-grade panic has taken hold in the city outside her modest Jackson Heights apartment. The subway turnstiles are being disinfected twice a day. The Diocese of Brooklyn has suspended Sunday Mass obligations for Catholics. The New York Police Department has alerted all of its precincts that Covid-19 is now categorized as a pandemic. This aptly conveys the breadth of the panic in New York City. Out of all the impacts on city life, what led you choose these three? We had many more examples, of course. But the ones we chose touched on everyday life — basic transportation, basic worship. And the NYPD detail allowed us to introduce the minor character of the commanding officer of a profoundly impacted police precinct in Elmhurst.

Capt. Jonathan Cermeli, the commanding officer of the 110th Precinct in Elmhurst, cannot believe the abrupt change in events. Only a week ago, at a 12th birthday party for his son, friends were discussing an issue that seemed entirely unrelated to their lives. It’s interesting the way you introduce a character briefly, suggesting by the use of his name and rank, that we will hear from him again. We knew that we wanted to come back to this police captain. Also, his anecdote about his son’s birthday seemed to capture that disconnection that was going on in many minds.

You guys hear about this virus? Again, a quote set off in italics. Why? As we’ve laid out, this became the convention for statements that people said were made at the time, but statements we ourselves had not heard. If you notice, in the next paragraph, Francisco Moya is quoted as saying something, in the conventional manner, because he said it later, looking back, in an interview with Annie.

Now Mayor Bill de Blasio has declared a state of emergency. His office will say it was in frequent contact with the city’s hospitals and regularly briefed elected officials and the public. But two local City Council members, Francisco Moya and Daniel Dromm, complain of receiving little guidance from City Hall.

“We felt like we were on our own,” Mr. Moya will later say.

Yimel, 40, is also on her own.

Like so many undocumented immigrants, she has no health insurance, no primary-care physician to call. She has been refusing offers of help from her roommates — who see her as their nurturing mother — and has barely let on to family in Mexico that she is sick. She has relied on prayer and citrus-infused tea to treat what she has been sarcastically calling her blessed cough.

But now the woman always up for a sassy selfie is not answering her phone, and her text about a cough has spooked her younger sister in the Bronx, Olivia Aldama, who senses what this means: Her beloved Chiquis is sick. What does “Chiquis” mean? Why didn’t you translate it? It is short for “Chiquita” and means “little one.” It is a common form of endearment in Spanish and is not meant literally (Yimel was not little) so we did not think that a translation would add any understanding. It also loans the scene verisimilitude and intimacy, and is clearly a term of endearment.

Olivia, 34, finishes her shift at a dry cleaners and hurries by subway to Jackson Heights. She enters Yimel’s darkened bedroom to find her sister moaning in her sleep, her cellphone buried in the sheets. Her breathing is labored, her lips parched, her tongue like white paper; she needs to go to the hospital.

I’m here, Olivia says, hugging her. I’m here now.

Olivia may not know everything about the sibling in her arms. That Yimel slept on the streets when she arrived in New York about 20 years ago. That she was a sex worker, enduring verbal and physical attacks under the elevated tracks in Jackson Heights. That she may still be. How do you know these things? From interviews with friends, fellow performers and local transgender-rights activists who had known Yimel from the first years after she arrived in the United States, up until the time of her death. In some cases, they recounted things that she had told them. In others, they had experienced certain things alongside her.

What Olivia knows is that her sister was identified at birth as a boy — a gender that Yimel later realized did not fit, but which she and her family still discuss as part of her past.

Growing up in Tlapa de Comonfort, a city in the mountains of southern Mexico, the child preferred playing dress-up with the family’s four daughters, incurring the wrath of their father. Tensions built up over the years until, one day, brimming with drink and shame, the man pulled out a knife and shouted, Kill yourself!

The only choice was to flee. But before being spirited across the border by smugglers, the teenager joined her mother in the cool of the Basilica of Guadalupe in Mexico City. There, the mother entrusted her own to the Virgin.

The new immigrant eventually found acceptance in Jackson Heights among gay and transgender people who had also fled intolerance in Latin America, and blossomed into Yimel Alvarado, who found her calling as an entertainer in the gay clubs around Roosevelt Avenue.

She has also become the bawdy, big-hearted matriarch of what is known as the Familia Alvarado, a tight-knit group whose members she has fed, clothed, counseled and often taken in. Over her apartment door hangs a sign that reassures: We Are So Good Together.

In recent years, though, Yimel has been going out less, gaining weight and drinking more. She often stays here in her bedroom, creating her glamorous outfits at a sewing machine, or sketching dress designs in a notebook. She also jots down comforting aphorisms she comes across.

Before giving up, try

And before dying, LIVE

Now, as Olivia struggles to help her sister sit up, a young Salvadoran man knocks on the door. He has been living in the apartment, sleeping on the couch, since Yimel learned that he was robbed at a homeless shelter.

Together they dress and guide the delirious Yimel toward the stairs. She sits and begins to ease herself down the steps, one by one — only to stop, exhausted.

A taxi is called. But the driver, suspecting that the woman slumped on the stairs has the virus, apologizes and leaves. In a fleeting moment of clarity, Yimel speaks: Call an ambulance. For the first time, the story focuses in depth on a character infected with the virus. It’s part intimate biography, part vivid and disturbing live action, all told in 600 words. What choices did you make in its development? We wanted to portray the first person who is taken to the hospital as indisputably individual and unmistakable for anyone else. This allowed us to subtly introduce the fact that every person admitted to the hospital was an individual, that behind every number, to paraphrase Gov. Cuomo, was a face. Yimel’s backstory was also gripping enough, as it was described by Olivia, her sister, to want to include it. The fact that she took in LGBTQ immigrants who had just arrived in the country, like the young man in this scene, conveyed a great deal about Yimel and about the neighborhood, which for years has been a destination for Latinx LGBTQ immigrants. Finally, the fact that the taxi driver was too afraid to transport this woman in duress spoke volumes about the worsening crisis, and the particularly wrenching choices it imposed on people. In addition, our desire to maintain a topspin to the story meant that we had to trim, condense, discard. We knew a lot more about what Yimel’s room looked like, for example, and what the names of her two dogs were — including one who trailed after her as she was all but carried to the stairwell. Too much detail can come off as showboating, and impede the narrative rhythm.

***

The ambulance carrying another possible Covid case pulls up to the trauma entrance of Elmhurst Hospital. The salmon-colored colossus traces its roots back nearly two centuries to a penitentiary hospital on what is now called Roosevelt Island, which treated the incarcerated, the poor and the neglected long before this 11-story complex opened in 1957.Others might see a drab municipal hospital short on amenities, tending to mostly the disadvantaged and uninsured. But Dr. Laura Iavicoli, 49, considers her safety-net hospital to be “the most magical place on earth,” with a skilled, committed staff and a diverse mix of patients who offer fresh challenges every day.

But never a challenge as daunting as this deadly virus, which first appeared late last year in the Chinese city of Wuhan, 7,500 miles from New York. Now it is here in Queens, where the recent confirmation of coronavirus cases at the hospital foretells dark days ahead.

At first the hospital considered itself prepared, with an interactive staff exercise about the virus in late January, a series of routine drills and access to four negative-pressure isolation rooms in the emergency department. Assumptions took hold, including that the virus would behave like other contagious diseases the hospital had prepared for but never seen, such as Ebola.

But assumptions are toppling. Influenza-like illnesses are rampant, while coronavirus cases are ticking up. And with access to testing severely limited, doctors are sending many patients, including some who may have Covid, home to isolate.

Hospital administrators are researching the 1918 influenza pandemic, communicating with medical experts around the world and meeting every night in a conference room to review models and statistics. But Dr. Iavicoli has become convinced that this virus cannot be outsmarted. It seems that the hospital is another character in this story. Absolutely. Just as we had dug into the history of the neighborhoods, so too did we dig into the history of Elmhurst Hospital. We even found the New York Times articles about its grand opening. What we basically landed on is having two characters representing the health-care world: One was a doctor at Elmhurst named Laura Iavicoli; the other was the hospital itself, which we tried to convey through the descriptions of the air filters and the lighting and the ever-changing look of the emergency room area.

The hospital’s initial isolation plan — based on protocols from several countries and agencies, including the Centers for Disease Control — hinged on yet another assumption: that the coronavirus reveals itself with fever, coughing and respiratory distress. Now doctors are realizing that diarrhea and malaise can also indicate Covid, which means that some contagious patients may have been inadvertently missed.

Every day, more emergency department space needs to be repurposed as isolation zones. The area reserved for treating coughs and minor cuts is now Covid. The critical care area, originally with seven beds, will soon have 20, all for Covid.

Green oxygen hoses snake across the floor, while blue air-filter hoses rise to the ceiling. Sick people cluster at the entrance, slouch in chairs, lie on stretchers along the dull pink walls. This is such a vivid description. Were you able to visit the hospital? Yes. After months of negotiations, photojournalist Todd Heisler and I were allowed to visit the hospital. We interviewed the CEO and several top officials in a board room, then suited up in full PPE — hazmat suit plus — and toured the emergency room. We simply had to see the inside so that we could recreate it in text. We then had many, many discussions with hospital officials to make sure that we had the terminology and the chronology correct. For example, I learned that “gurney” is an antiquated term.

Now paramedics in protective suits wheel in another: Yimel Alvarado.

She is placed on a bed in the hallway, next to a young woman holding her stomach and crying out in agony. Briefly snapped from her delirium, Yimel looks over with evident compassion, but soon she is gone again, speaking in the language of hallucination as she stares at the hospital monitors in the corridor:

That’s why I don’t watch television. They keep changing the channel.

Without the oxygen she received in the ambulance, Yimel becomes weaker. A sip of water causes her to convulse in coughs, sending Olivia running for help. A nurse rushes over to check the oxygenation of Yimel’s blood.

Several hospital workers are soon gathered around Yimel. First in English, then in Spanish, they ask: Have you traveled? Have you had a cough? Have you had a high fever? For how long?

Olivia repeats the answers she heard her sister give to paramedics in the ambulance: No. Yes. Yes. Four days.

Yimel is wheeled beyond a set of glass doors. Hours later, a doctor emerges to inform Olivia that her sister is in critical condition with pneumonia and would be dead if she hadn’t been brought to the hospital.

Five days ago, Yimel was performing at a nightclub; now she is in intensive care. By morning she will be unconscious, intubated and encased in a plastic tent. Who is the source of this passage that describes Yimel’s deteriorating condition? Her sister, Olivia, who methodically recounted this day from beginning to end in astounding detail, which she repeated for us several times. She remembered much more than what we could include.

Earlier on this Saturday, Mr. Trump asserted that the country’s relatively low number of coronavirus-related deaths — about 50 so far, he said — was because of “a lot of good decisions.” Tomorrow he will describe the virus as “something that we have tremendous control of.” Why did you choose to introduce Trump and track his comments over two days? He was the President of the United States. He was providing assurances publicly while, as we later learned from Bob Woodward, being very pessimistic in private. His words again reflect the pandemic-related disconnect going on in the country that may have fostered the doubts about mask-wearing and social distancing, and the dismissive belief among some that this was little more than a bad flu. What was being experienced in Queens at that time is now being experienced throughout the country, raising the question whether the country — or the Trump administration — ever had “tremendous control” of the virus.

But these upbeat assertions belie what is being experienced at Elmhurst Hospital, where Covid cases and flulike illnesses continue their ominous rise. Near midnight, Dr. Iavicoli talks by phone with two other emergency department supervisors, Dr. Stuart Kessler and Dr. Phillip Fairweather, to assess the damage of another harrowing day.

Dr. Iavicoli, who has expertise in emergency management, recommends an aggressive requirement that emergency department staff wear full personal protective equipment — gown, gloves, goggles and N95 mask — at all times.

The three doctors agree. Now the entire department is officially a “hot zone,” based on a new assumption: Everyone is likely to have Covid.

This is such a dramatic ending to this section. Why did you choose it? I liked the chance to return to the concept of assumptions that was introduced earlier in this section. And we tried to end each section with something memorable, whether it’s a strong, catch-your-breath statement (“Everyone is likely to have Covid”) or something quieter, as when a character feels the sudden weight of loneliness now that his partner is dead.Wednesday, March 18

‘I do want people to be calm, because we’re going to win this.’

— PRESIDENT TRUMP

Why did you quote Donald Trump here? Not to be flip, but why not? This is what the President of the United States was saying to the country on or around Wednesday, March 18. There was the theoretical thought in Washington, and the grounded-in-reality thought in Queens.A stillness settles over the city. Events by which New York measures time — the St. Patrick’s Day Parade, for one — have been canceled. Schools for more than a million students are closed. Religious services are suspended. Transit hubs are empty. Skyscrapers are vacant. Broadway is dark.

Coursing through the quiet is a palpable anxiety, a collective bracing for the blow to come.

In the upstairs apartment of a two-family house in Woodside, Dawa Sherpa, the Uber driver from Nepal, tries to scrub away what he cannot see but fears is present. Four days have gone by, a passage of time that you use to sum up the psychological and civid impact, followed by the introduction of another major character. Why did you feel set it up like that instead of leading with Dawa? The first two graphs are intended to convey the surreality that had overtaken New York City. Initially there were more examples of a stilled city, but we winnowed it down for pacing.We were trying to create an establishing shot, as in a movie: the panorama of the metropolis, and then drilling down to one person representative of the metropolis. Zooming out and zooming in, being general and then being specific: God’s view, and then the view of a scared Uber driver in Woodside, Queens.

He cleans the stairwell, where the shoes of his three sons, 18, 13 and 6, form a neat row up the steps. He cleans the bedrooms, the kitchen and the living room, which features a torn map of the subway system and a large Buddhist shrine with three key figures: Shakyamuni Buddha, Guru Rinpoche and Chenrezig.

On the altar sit seven silver bowls that are filled with water in the morning and emptied at night, a silver chalice brimming with an offering of amber-colored tea — and a large bottle of hand sanitizer.

Dawa is 50, short and husky, his black hair flecked with gray. Born in a speck of a farming village on a mountaintop in the Himalayas, he moved with his family to Kathmandu, then was sent at the age of 10 to a Buddhist monastery, where life became a spiritual boot camp of prayer, chores and study. Failure to know one’s lessons could result in a beating.

When he was about 20, he jumped over a monastery wall to see what was going on in the world. He never returned. How were you able to find characters with such interesting back stories? A narrative writer once told me he “auditions” characters as he cast about for figures whose stories are the most compelling and accessible. Annie and I, along with a lot of help from Jo Corona, just kept listening to people in the community. Following up on throwaway lines, looking at obits and memorials on Facebook, reaching out to community leaders. We wanted characters from several ethnic communities in the neighborhood. We also wanted a mix of people who got sick and lived, and got sick and, sadly, died. I had spent time with the president of the United Sherpa Association and was thinking of him as a possible character until he introduced me to two members of the association, including the Uber driver Dawa Sherpa. When he told me that he had been a Buddhist monk, I was intrigued. When he told me he spent several nights in a chair at Elmhurst Hospital, waiting for a bed, I was sold. He also had hospital documentation, and his wife corroborated everything he told me.

The former monk traveled to China to help his father’s import business, then to Japan, where he worked at a Toyota factory, and then, in 1996, to the United States, which he understood to be “a freedom country.”

He gravitated toward Jackson Heights, married Sita Rai, a woman he had met at a wedding in Kathmandu, and began assembling a familiar immigrant résumé: clerk in a school-supply store; cook in a Chinese restaurant; driver for a manufacturing firm; delivery man for Domino’s Pizza; taxi driver, working a 12-hour overnight shift.

Four years ago, Dawa switched to driving for Uber, shuttling customers around the tristate area in his black Toyota S.U.V. In recent weeks, he has listened constantly to the news radio station 1010 WINS in his car for updates on the pandemic’s progression.

Then, two weeks ago, two customers coughed in his back seat. He drove home and systematically wiped down the seats, the door handles, everything, in mists of Lysol spray. He hasn’t driven for Uber since. I love the phrase “mists of Lysol spray.” It was just another way to convey a man frantically spraying disinfectant against an invisible enemy. There was also something faintly spiritual about “mists” — reminding me of the holy water that Catholic priests spray with an aspergillum during the Easter season.

And it may be a trick of the mind, but Dawa does not feel 100 percent.

***

Not a half-mile away, dozens of families flock to a commercial stretch along 73rd Street, a few steps from Roosevelt Avenue. This is the Little Bangladesh section of Jackson Heights, a medley of groceries, restaurants and shops that cater to immigrants from Dhaka, Chittagong, Khulna, Sylhet.Gone for now are the days when men discussed news events in Bengali over samosas and tea, while women browsed the saris in the boutiques and children made difficult selections in the sweet shops. Gone is the sleepy air, redolent of spices. How do you know the immigrant community of Queens so intimately? I was born in Jackson Heights/Elmhurst and have some understanding of the changing demographics. Annie has been reporting on this part of Queens for more than a decade, specifically its large Latino population (more than 50 percent of the population in some of these zip codes is Hispanic). For this piece, we also enlisted the help of Abu Taher, a Bangladeshi-born journalist with deep connections to this community, and spoke at length to local community leaders, including an imam, also originally from Bangladesh, who performed funeral prayers for Covid victims and provided food and information for the community. The Chowdhury family also described Little Bangladesh and the activities that happened there. We wanted to include this community, as it was devastated by the pandemic.

Instead, uneasiness has set in, as people mill together in a determined search for food and supplies. With schools closed, children will be staying home, taking classes online for who knows how long. So mothers heap bags of rice and tins of oil into the family cars, while fathers carry out slabs of meat to store in newly bought freezers, as if stocking up for a lengthy siege.

All around, people are falling sick. A sergeant who analyzes crime statistics for Captain Cermeli at the 110th precinct. A jeweler who helps to run a soccer league in Corona. The pastor of St. Bartholomew Roman Catholic Church in Elmhurst.

Along and around 73rd Street, lines snake outside grocery stores, and some pharmacy shelves have been picked clean. The same scene is playing out in other areas nearby: Little India, Little Colombia, Little Manila. People who have known faraway conflict are steeling for war.

Friday, March 20

‘We have not gone through something like this across our whole city in generations.’

— MAYOR BILL DE BLASIO OF NEW YORK

The structure of the narrative is digressive in nature as you switch seamlessly from one major character to another. What was the process of organization? We began with the structure — defining an area of Queens, defining the chronology — and then, almost organically, following the journey of the characters we had chosen. The dates of major events in the lives of our characters helped determine the order of their appearance and reappearance in the narrative. We built and constantly updated a timeline with new information. It became a bit unwieldy, but it was more or less obvious from looking at it which dates would have to be included. How did you assemble the timeline — on a whiteboard, index cards, Google Docs? — and keep track of drafts and revisions when/if you were all working remotely? Since we were all working remotely, and denied the collaborative benefits of meeting together in the newsroom, there was no sense in using a whiteboard or keeping index cards that we could share. (Not sure we would have used these techniques even if we HAD access to the newsroom.) We relied on several Google Docs. An early one compiled notes from interviews and research, for example; others had various drafts and revisions. A central Google Doc was a timeline that soon groaned with every known thought, it seemed. But this document became invaluable in understanding where all the characters were in their journeys, as well as what was going on in the city, state, and country around them.In a brick building in Corona, 11 members of an extended family from Ecuador, young and old, live in a three-bedroom apartment. Two are sick: Rosa Lema, 41, with a fever, and her brother-in-law, with a violent cough.

Now, late this afternoon — on a day when Mr. Cuomo announces a shutdown for much of the state — Rosa is notified by telephone that her mother, Vicenta Flores, has fainted during a dialysis session at Elmhurst Hospital, and a family member needs to take her to the emergency room.

Rosa, a petite woman with high cheekbones and sleek dark hair, spent days disinfecting the kitchen and the well-trafficked bathroom, with its shower handle for her parents to grip. She encouraged her mother, who is 77, to stay in her small room between dialysis appointments, and bought sugar-free Robitussin for diabetics to treat what she thought was her mother’s minor cold.

These precautions were futile. Rosa calls her brother Jorge, who lives nearby. He rushes to the hospital.

It was never the plan to jam so many people into Rosa’s apartment. To stuff the living room bookshelves with clothes. To pile dusty boots and sparkly children’s shoes outside the front door.

But a few months ago, Rosa’s sister Carmen and her family appeared at her door in Red Cross blankets after losing their home in a fire. So now six adults, five children, two cats and a dog live packed together, amid the discarded baubles that Vicenta has picked up while collecting cans for deposit money, which she sends to her mother in Ecuador.

Jorge calls back, worried; a line of more than 100 people is unspooling from the emergency room. Rosa tells him to alert the hospital staff that their mother is in a wheelchair, sick and listless. “Unspooling.” Why choose that word? Just challenging oneself to find fresh language and avoid the tired and cliched. Also, “unspooling” conveys something on the verge of being out of control.

Soon Rosa’s brother calls again, this time with a doctor who has questions. Has Vicenta had a fever? Has anyone else in the family been ill?

Yes. Both Rosa and her mother have not been feeling well. But if her mother has contracted the virus, Rosa wonders where. At the dialysis clinic? During visits to another Queens hospital where her 83-year-old husband, José Redentor Lema — Rosa’s father — had been recovering after complications from pancreatic surgery?

What about the living room, where Vicenta sits during the day, playing with the cats or stroking her granddaughters’ ponytails? At night the sofas become beds for Rosa’s sister, her husband and their twins; he is a tile layer who became ill when the virus swept through his construction crew.

At Elmhurst, hospital workers lift her mother onto a bed and wheel her away, leaving Jorge to take in the long trail of the sick and worried, some so depleted they are lying on the ground. What a terrible scene, so meticulously rendered. How was it reported? Annie interviewed both Rosa Lema and Jorge Lema, who called each other after their mother fainted at dialysis, and in this way was able to know what was happening on either end of the call (in the apartment; outside the hospital). She also interviewed Rosa’s three sisters and two of Rosa’s nieces, who grew up with their grandparents in Ecuador and now live in Florida. From these interviews, she learned about each member of the family and how Rosa Lema’s household had recently become crowded with close to a dozen occupants. She focused on details from her interviews (Robitussin for diabetics; Red Cross blankets) that stood out and from her visit to Rosa Lema’s home (the handle in the shower stall for her parents to grip, for example).

Rosa thinks about their mother’s toughness. Cooking corn cakes over open flames for the family in their hometown, Biblián. Raising six children while her husband traveled the country building roads. Then, when her children emigrated to the United States, raising some of their children.

Once she was in Queens, the tiny woman, not five feet tall, learned to navigate the big-city streets as she collected cans. She even emerged from a six-week coma after being struck by a car.

Ella va a estar bien. This is what Rosa will tell her siblings. She will be fine.

But what will she tell her father, who has recently been moved to a rehabilitation center? He is so attached to his wife of 52 years that he always asks the same thing if she is even a minute late coming home.

Where is Vicenta? Where is Vicenta?

Saturday, March 21

‘NYC: I need you to stay home.’

— DR. DAVE A. CHOKSHI, CHIEF POPULATION HEALTH OFFICER FOR NEW YORK’S PUBLIC HOSPITAL SYSTEM

A mile and a half away in Woodside, in another brick apartment building, Jack Wongserat, the chef, has shared his fears of the coronavirus with his partner, Joe Farris, who has not been as anxious. Until now. Jack has a 103-degree fever.

Theirs has been a New York romance: A Thai immigrant named Jack, short and compact, meets an Alabama native named Joe, tall and thin, in a bar on the Bowery in 2005. They engage in the pro forma exchange of telephone numbers, but then Jack surprises Joe by calling.

“He courted me,” Joe says.

In the city’s close-knit community of Thai cuisine, Jack, 53, is known as exacting but nurturing: rigid about hygiene and promptness and then, after the last curried dish has been served, available for a glass of Riesling and an encouraging chat with colleagues new to America.

Drawing on his own life — born in the Thai city of Ubon Ratchathani, losing both parents when he was young, emigrating in 1990 with no prospects — Jack tells them to be strong. He spins stories about his luck at casinos, and invites them to watch his beloved Giants and share spicy food he has cooked that will taste like home.

They nickname him Mama. A terrific profile in just three paragraphs. An earlier version had much more. I knew the name of the bar in the Bowery, what they were drinking, other details. I also spoke to several of Jack’s work colleagues, who told me that he loved to travel, loved to go to Las Vegas and sit with a Corona, playing the slots. But concision was necessary, especially since we needed to give the backgrounds of two people, not just one.

His partner, Joe, 58, grew up in the small city of Jasper and studied music at the University of Alabama. He taught English in Taiwan for a year, then moved in the early ’90s to New York. After a long stretch waiting tables, he shifted to market research, and now works as a project manager from the apartment he has shared with Jack for two years.

In one corner are Jack’s small shrine to the Buddha and a mismatched collection of china for the restaurant he hopes to open one day. In another corner sits the digital piano he bought for Joe to reignite his passion for music.

Now, on this Saturday morning, Jack is texting Joe from their bedroom.

11:43 a.m.: My test is positive

11:43 a.m.: Dr. said drink more water

11:45 a.m.: Take the Virus medicine

11:50 a.m.: Start separating fork spoon

11:50 a.m.: Use the mask protection

11:50 a.m.: Every time

12:07 p.m.: Sorry about that

Text messages are a great way to vary documentation. How did you get them and why did you use them directly instead of as confirmation? I visited Joe, Jack’s partner, twice and had many, many phone conversations. At one point he told me that he and Jack were trying to remain socially distant within their own apartment, and were communicating often by text. I asked whether any of those texts were extant. Luckily, the answer was yes. When he sent me these texts, we then wanted to make sure that the heartbreaking last line — “Sorry about that” — was related to the virus, and not to some domestic misunderstanding. But Joe said yes, it was about the virus; Jack felt bad about bringing it into their home.Monday, March 23

‘The hardship will end. It will end soon. Normal life will return.’

— PRESIDENT TRUMP

The skies are leaden, a wintry mix falling. All in keeping with the mood of Queens.

Inside Elmhurst Hospital, Vicenta Flores is on a ventilator, unconscious and alone. Visitors are not allowed, but many in her family’s small apartment in Corona are too sick to see her anyway, including two grandchildren sharing a nebulizer meant for asthma. Rosa Lema, Vicenta’s daughter, is so ill that she has gotten tested for the coronavirus.

Meanwhile, the entertainer Yimel Alvarado remains sedated and on a ventilator in her clear plastic cocoon. With the help of an English-speaking member of the Familia Alvarado, her sister Olivia has been calling twice a day to check on Yimel, whose own test result has finally come in: positive.

Covid cases have all but overtaken the emergency department. Just weeks ago, the prevailing wisdom held that the hospital’s four negative-pressure isolation rooms could handle whatever infectious cases came in. The thought now seems absurd.

For Dr. Stuart Kessler, the emergency department’s director, the days are one protracted crisis under fluorescent lights. A Queens native who grew up in Bayside, seven miles to the east, he has hound-dog eyes and a seen-it-all air earned from decades as an emergency-medicine physician in big-city hospitals.

But he has never seen any disease progress like this virus, and he is urging peers around the country to reject conventional thought and prepare for something entirely unfamiliar. His words of caution do not seem to register. If you haven’t lived through it, he decides, you cannot understand it. How long did this story take from idea to publication? Cliff Levy, the Metro editor, and I began talking about the project in mid-April; my first memo to him was on April 19th. We finished the reporting, writing, and editing on the day after Thanksgiving.

Outside the hospital, gunmetal barricades guide a trail of rain-battered people toward a testing site in a tent near the emergency department entrance. Bent beneath umbrellas, hunched against the cold, they form a daily column of dread. A rich paragraph from “gunmetal barricades” and “rain-battered” people to “a daily column of dread.” Was it your first take, or did the description go through much revision? A lot of revision. It’s like trying to crack a code, a matter of calibration. We also had photographs and video of that day, and that scene, which made the describing a lot easier.

Francisco Moya, the local councilman, drives past the line after delivering 1,000 face masks to the hospital where he was born 46 years ago and once worked as an administrator. The son of Ecuadorean immigrants who settled in Corona, he is a familiar, bearded presence around here, having also served as a community organizer and state assemblyman.

He is heart-stricken and angered by the sight of so many people, many of them uninsured immigrants, huddled in desperation. It seems like a scene from some war-torn country, not his own.

As the city’s confirmed cases double about every week, Mr. Moya is among those sounding the alarm. On social media and in calls to City Hall, he asserts that Elmhurst Hospital is over capacity and in dire need of doctors, nurses, ventilators and personal protective equipment.

It is true: Many in Queens are in short supply of nearly everything, save despair. But dozens of local organizations are working to fill the void.

A few blocks from Elmhurst Hospital, a young imam from Bangladesh is converting his mosque, An-Noor Cultural Center, into a makeshift storehouse; the prayer room’s carpet will soon be covered with donated halal food. With the wizardry of his 13-year-old son, he is also posting daily videos on social media to keep his isolated congregants informed.

In Woodside, an out-of-work contractor from Ecuador volunteers his services on Facebook to fellow congregants at Aliento de Vida church. “My brothers God bless you all,” he writes. “If anybody is in need of supplies or has an emergency and needs transportation, I offer to take you completely for free.”

And in Jackson Heights, an old Lutheran church hums with assembly-line precision. The building is now a Buddhist temple and headquarters for the United Sherpa Association, a resource for immigrants from Nepal, Tibet and Bhutan. Among its members is Dawa Sherpa, the Uber driver, who is active in its youth sports program.

On the second floor, where a white scarf, called a khata, is draped over a beam as a sign of welcome, volunteers are making care packages for the sick, homebound and scared.

They have been scrounging round-the-clock for gloves and face masks and hand sanitizer, with members in the import business calling contacts in Asia late at night. But they cannot seem to get enough of a once-plentiful item: Tylenol.

Joe Farris, who lives a short block from the Sherpa building, has been on the same quest. His partner, Jack Wongserat, is trying to stay fit during his illness, doing stretches on a blanket he has laid on the floor beside the bed. But his dry coughs are incessant.

Seeking to ease Jack’s pain, Joe walks the unnaturally quiet Queens streets in search of isopropyl alcohol, zinc, vitamin C tablets and Tylenol. None at the Duane Reade drugstore. None at the Walgreens. The best he can do is to secure two thermometers.

Joe is also unwell. He is coughing and has lost his sense of smell, which is said to be a Covid symptom. The other day he put his wrist to his nose and could not detect his cologne.

The two men at least have a plan. They wipe everything with alcohol swabs and keep separate silverware in plastic containers marked with their names. Joe sleeps in the living room.

Even so, Jack seems to be thinking ahead. While Joe putters in the kitchen where Jack’s spices take up four shelves, he hears his partner mutter alarming words as he shuffles past.

I’m not afraid of dying. I’m 53. I’ve had a good life.

How did the reporting team deal with the emotional toll of covering such a tragic story? Annie and I aren’t comfortable talking about the emotional impact on us — the focus should be on those we wrote about. They agreed to talk to us about some of the worst days of their lives, often in tears, and we are just so grateful to them for having shared their stories with us.Tuesday, March 24

‘The number of new cases continues to increase unabated.’

— GOVERNOR CUOMO

Less than a mile to the north, in East Elmhurst, Mahdia Chowdhury is home from Cornell University and losing sleep in her family’s small second-floor apartment, in the bedroom she shares with her two teenage brothers. You’re so specific about distances. Why? And how did you compute them? We created our own map with all the major locations, and then used Google maps and other means to measure the distances. The specificity mattered so that readers who have never been to this part of Queens — who have never been to New York! — could get a sense of how close the locations are to one another.

Outside, the ambulances are so common that at night their lights paint her bedroom ceiling red. Inside, her father, Shamsul, is getting sicker by the day.

A few days ago, he stopped going to his mosque and returned the yellow Toyota Prius that he leased with a partner to a taxi garage in Long Island City, as she had begged him to do because of risks to his health. Too late.

Now, every night, he comes to her room to ask whether his “dysentery” — his term for a fever and diarrhea — means that he has Covid.

No, she fibs to reassure him. You’re fine.

Although her parents sleep in the same bed, Mahdia is not as worried about her mother, Tarana, 47, who still works serving food and cleaning up in the United Airlines lounge at nearby La Guardia Airport. It is mostly empty now, the once-constant roar of jets overhead all but silenced.

Her father is the one who concerns her. Setting aside her college assignments to research Covid symptoms, she has become convinced that he is infected and, as a diabetic and smoker, at great risk. He is 48.

Just days ago, Mahdia was in the library of her hilly campus 240 miles away, cramming for midterm exams. Now she lies awake as her brothers sleep. Shamsul seems weaker. He scarcely touches the rice the family leaves outside his bedroom door, beneath a talisman of a blue eye meant to ward off evil.

She thinks about their father’s quiet sacrifices. In the Bangladeshi city of Sylhet, he owned land and had a master’s degree. He was part of the privileged class.

The earnest and meticulous Shamsul gave all this up in 2009 to provide more opportunity for his children in the United States, where, instead of managing operations at a bank in Sylhet, he took Mahdia and her brothers to school every morning in the taxi he drove 10 hours a day.

He no longer seems as depressed as when they first arrived, though the family’s finances remain a worry. He fears that he became a New York cabdriver a generation too late; that the taxi industry was collapsing even before the pandemic; that he and his wife may never afford a house.

Now Shamsul shuffles to the bathroom in loose pajamas and flip-flops, shielding his eyes against the light. Do you think I have it?

Mahdia, petite and practical, her thick black hair kept at shoulder’s length, usually handles the family’s paperwork, a familiar job for a first child of immigrants. She will be the one to decide what to do.

Should she hold off on sending him to Elmhurst Hospital, rumored to be overrun? Or should she get him there while she can? She envisions herself frantically dialing 911 some night, only to find that all the ambulances have already been dispatched.

Another squalling ambulance hurries down their block, another sick person being taken away. From her window she has seen the used rubber gloves left by paramedics on the street. Do I assume correctly that Mahdia is the principal source for this session? Yes, Mahdia was the principal source for this section, although Annie also interviewed her father in person, as well as her mother and two brothers. Annie found her through Cornell students who had launched a GoFundMe campaign for pharmacists from Bangladesh, and Mahdia sat with Annie for two hours in a park in East Elmhurst, discussing her family’s experience. There were also several follow-up telephone interviews. Annie and Todd Heisler also documented the day the family loaded up their vehicle to take Mahdia back to Cornell for the fall semester, and later returned to interview Shamsul and photograph the family at home.

Wednesday, March 25

‘If I could just say to every American: We’ll get through this.’

— VICE PRESIDENT MIKE PENCE

Jack Wongserat demands to be handed a takeout container to fill an order. He becomes annoyed when one is not made available, then sits down to dial the telephone.

But there are no takeout containers. There is no telephone. Nor is he back working at a Thai restaurant in Manhattan on this cool and cloudy morning. Jack is in his Woodside apartment, in the throes of a delusion.

By tonight, much of the country will be disabused of any illusions about the virus, in part because of Jack. Why the forward projection? Because we know what was to come. The day of the 13 deaths became a national, if not international, news story. Along with the video from Dr. Colleen Smith, it helped draw attention to the plight of hospital workers at Elmhurst Hospital and the need for extra workers and supplies. It also put the country on notice: The virus was real and it was lethal and pushing an American hospital to the brink.

His partner, Joe, settles him into a plush chair in their bedroom, then eases him onto the bed, hoping that he will sleep. But soon Jack is gasping for air. As Joe hurriedly turns him on his side, they both crash to the floor.

Joe dials 911 and tries to follow the dispatcher’s instructions for administering CPR. The ambulance, of course, seems to take forever.

The paramedics hurl the tan chair onto the bed to create room, then take Jack by stretcher down to the courtyard. As five medics wheel him to the ambulance, his stomach rises and falls in frantic measure to his search for breath.

Oh my dear, says a neighbor watching from her window. Oh no, oh my Lord, please bless him.

Racing to Elmhurst Hospital on foot, Joe finds Jack intubated and unconscious on a bed in the controlled frenzy of the overcrowded emergency department. Beds are wheeled past, including one bearing a patient who appears to be dead.

A drawn curtain in a corner provides minimal privacy for two men who have shared an Alabama-Thailand bond for 15 years. On the faint chance that Jack can hear, Joe talks.

Everything is going to be OK. You’re at peace.

A doctor explains that a sustained loss of oxygen has caused significant and permanent brain damage. He excuses himself to allow Joe time to decide whether everything or nothing should be done to keep Jack alive.

For Joe, the only option is the one Jack would want. He accepts and signs the Do Not Resuscitate form.

Sitting at the bedside of his life partner, Joe loses all sense of time. At one point Jack’s heartbeat becomes erratic, but a physician who rushes over is advised by a colleague not to assist: The patient is a D.N.R.

Jack’s heart stops. Two social workers appear by Joe’s side to provide comfort and a list of funeral homes. One recommends that he make arrangements immediately, given the sudden demand. This is such a dramatic scene. How did it come together? Joe told me this story several times. In addition, I went to the apartment and basically took notes and photographed every inch of it. I saw the chair in the bedroom, for example. Thanks to our freelance partner, Jo Corona, we also had a video taken from a window by a neighbor that showed Jack being taken out of the building by paramedics. You can see his stomach rising and falling as he’s straining for breath. The section went through several revisions to tighten and strengthen it. This meant stripping it of some details so as to avoid diluting other, more important details. I did want to emphasize, though, Joe’s sense of losing time. Anyone who has been in a similar situation knows that feeling — that none of this is real. We wanted to convey that unsettling sense that this was all a dream, a nightmare.

Jack Wongserat is one of 13 people to die at Elmhurst Hospital in the span of 24 hours. The hospital code for emergency intervention — “Team 700” — resounds over the loudspeaker, while a recently delivered refrigerated truck hums outside, prepared to receive.

The crush of patients is so great that emergency doctors and nurses are no longer donning fresh N95 masks every time they approach a new patient. It would take too long and burn through too many.

An Elmhurst Hospital doctor’s plea for help, conveyed in a video published by The New York Times, amplifies the increasingly grim situation. The doctor, Colleen Smith, says the emergency department is seeing 400 patients a day — nearly twice the normal complement — while supplies dwindle and crowds wait for medical assessments.

“This is bad. People are dying,” Dr. Smith says in the video. “We don’t have the tools that we need in the emergency department and in the hospital to take care of them.”

By nightfall, the borough of Queens — and, specifically, Elmhurst Hospital — will become known as the epicenter of the pandemic in New York, if not the United States. For many Americans, the coronavirus will move from abstract threat to real-life horror.