Even if they bear no physical wounds, soldiers returning home face a host of challenges, including adjusting to the slow pace of normal life. Photo by David Guttenfelder/The Associated Press

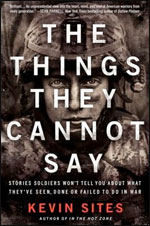

Do men and women cover wars differently, I wonder? Stereotyping is a very terrible thing for a journalist, but after 25 years as a war correspondent I have yet to meet a fellow female colleague who really cared what they were being shot at with or bombed by—some of us can barely tell the rather crucial difference between incoming and outgoing fire—or a male who was preoccupied by how mothers were feeding and schooling their children through the conflict. All of which meant I started reading "The Things They Cannot Say" with mounting annoyance. In the world of its author, Kevin Sites, women don’t exist as active participants. They are the wives left behind or grieving mothers.

Instead, it’s all boys with toys. Sites talks excitedly of being "shuttled back and forth between battleships and aircraft carriers." His focus in reporting war is the bang-bang rather than the people. After all, this is someone who set out to cover every major war in a year—managing to get to 20 wars—calling the result "Kevin Sites in the Hot Zone." That’s not journalism, Kevin; that’s just you going to dangerous places.

However, as I read on I realized Sites had hit upon an important theme. There are plenty of books out there of action in Iraq or Afghanistan, correspondents vying to be with the brigades that suffered most and writing vividly of life under fire. But what about what happens when those soldiers go home? What of the effects of war you can’t see and don’t want to talk about—or perhaps we don’t want to hear? What Sites calls "the things they cannot say."

More than 11 years of fighting, where some units are now on their fifth deployment, has not only left more than 6,600 American soldiers dead and tens of thousands wounded, but a generation scarred in a far less visible way. It is this frontline back home that is the focus of Sites’s book as he tried to get soldiers to talk about their experiences.

I read this book the same week that in my country, Britain, a young soldier who had survived a Taliban bomb a year earlier was found hanged while on home leave near Swansea. Trooper Robert Griffiths, 24, had been driving a Scimitar tank when it was hit by a Taliban Improvised Explosive Device. Remarkably, its new armor plating meant he walked away unhurt. At the time he said, "It was obviously a shock but I’ve never had such a buzz in my life." Yet after returning from Afghanistan he hung himself.

The latest figures show more American soldiers died last year from committing suicide than in combat. In other words, we may be seeing fewer physical injuries as we have left Iraq and pull out from Afghanistan, but we are stocking up a huge problem for the future.

Anyone who has spent time on frontlines knows you cannot experience war up close without it affecting you, particularly over protracted periods. After all that life on the edge, the hardest thing can be adjusting to normal life. A war photographer I have worked with came back from one arduous trip to find his wife with carpet samples. "You want me to care about choosing stair carpets when I’ve been watching people all around me die?" he wanted to scream. Who can forget the scene in Kathryn Bigelow’s film "The Hurt Locker" when Sergeant William James returns home from Iraq and goes grocery shopping with his wife? Pushing an empty cart, staring at all the shelves of cereals, he is overwhelmed.

One of the saddest stories in "The Things They Cannot Say" is that of Corporal William Wold, whom Sites meets in Iraq and interviews just after he has killed six Iraqis. Wold is only 21 and tells Sites he has already killed 12 people. When he goes home, he jumps uncontrollably at Fourth of July firecrackers and ends up in a spiral of drugs that eventually costs him his life.

Sites writes of survivor’s guilt, telling the story of Lance Corporal James Sperry who lost 20 friends in Iraq and back home tries to blot out his woes with what he calls "crotch rockets," high-speed motorbikes that he rode on the freeway while drunk on tequila. Fortunately, he gets help.

This is a disturbing book, not least as Sites confesses to his own breakdown. He spent much of his 2009-2010 Nieman year drinking, smoking, taking drugs, self-harming and feeling worthless. He thinks society should know what they are sending soldiers to. I think he’s right, and policymakers should read this book. I would like to have seen some exploration of what it’s like fighting a war when your political leaders have sent you there on spurious grounds, such as Iraq, or cannot explain what you are trying to achieve, such as Afghanistan. It wasn’t clear, however, that getting soldiers to open up helped them. Indeed, in some of the cases, Sites clearly reawakened ghosts. He’s not a professional, after all.

In one of the book’s most disturbing scenes, Sites recounts diving off the island of Bonaire with a former Dutch soldier. They do a "bounce" dive, where you bounce to a depth below normal limits, risking a pulmonary or cerebral embolism. As they get to 296 feet, Sites wonders about losing himself in the seductive blackness below. "Is this the place where one need never think of war again?" he asks. He resists, and when they come back to the top they are elated, high-fiving each other, happy to have at least momentarily rediscovered the adrenaline of war.

All war correspondents know that feeling. Maybe it’s why we keep going back. Maybe, too, if Sites stopped and talked to some of the women trying to keep families together in the battle zones of our generation’s wars, he would realize war is an ugly thing not just for those who fight it.

Christina Lamb, a 1994 Nieman Fellow, is foreign affairs correspondent for The Sunday Times. She was appointed Officer of the Order of the British Empire in the U.K.’s 2013 New Year’s Honours List for "services to journalism."