China sent its first Nieman Fellow to Harvard in 1981. The total now stands at 24

Winter is Nieman’s season of dreams. The applications pour in from elite newsrooms and single-person startups, from G8 nations and nearly invisible economies. Most of the international files arrive electronically, but some come to us handwritten, penned and pieced together by journalists living in places where Internet access is sporadic or unavailable. Uniting them all is a hunger for the education, support and transformation that is the Nieman Fellowship year.

When the Nieman Foundation was founded in 1938, only Americans could apply. Our archives are rich with the plans and longings of U.S. journalists who for three-quarters of a century have sought the direction promised by a year at Harvard. On the occasion of our 75th anniversary this past fall, I read one archived application typed on crisp vellum paper. The journalist’s credentials included coverage of township committee meetings held in converted farmhouses and a series that placed third in the American Trucking Association’s annual Award for Distinguished Public Service. He had advanced to a larger newspaper, Newsday, and the forces shaping Long Island compelled him to seek new reporting muscle at Harvard, studying the emerging field of urban and regional planning.

“It is to procure this education that I apply for a Nieman Fellowship,” he wrote, and in sturdy black ink signed his name, Robert A. Caro. Caro’s first book, “The Power Broker: Robert Moses and the Fall of New York,” would emerge from his Nieman studies, and he would go on to become one of the nation’s preeminent biographers.

But when Nieman began accepting international journalists in 1951 a new, more urgent dimension was added to the applicant pool—journalists seeking not only edification but an escape from persecution and sometimes prosecution; relief from censorship; and a set of colleagues with shared values to help them recalibrate an ambition for what journalism makes possible.

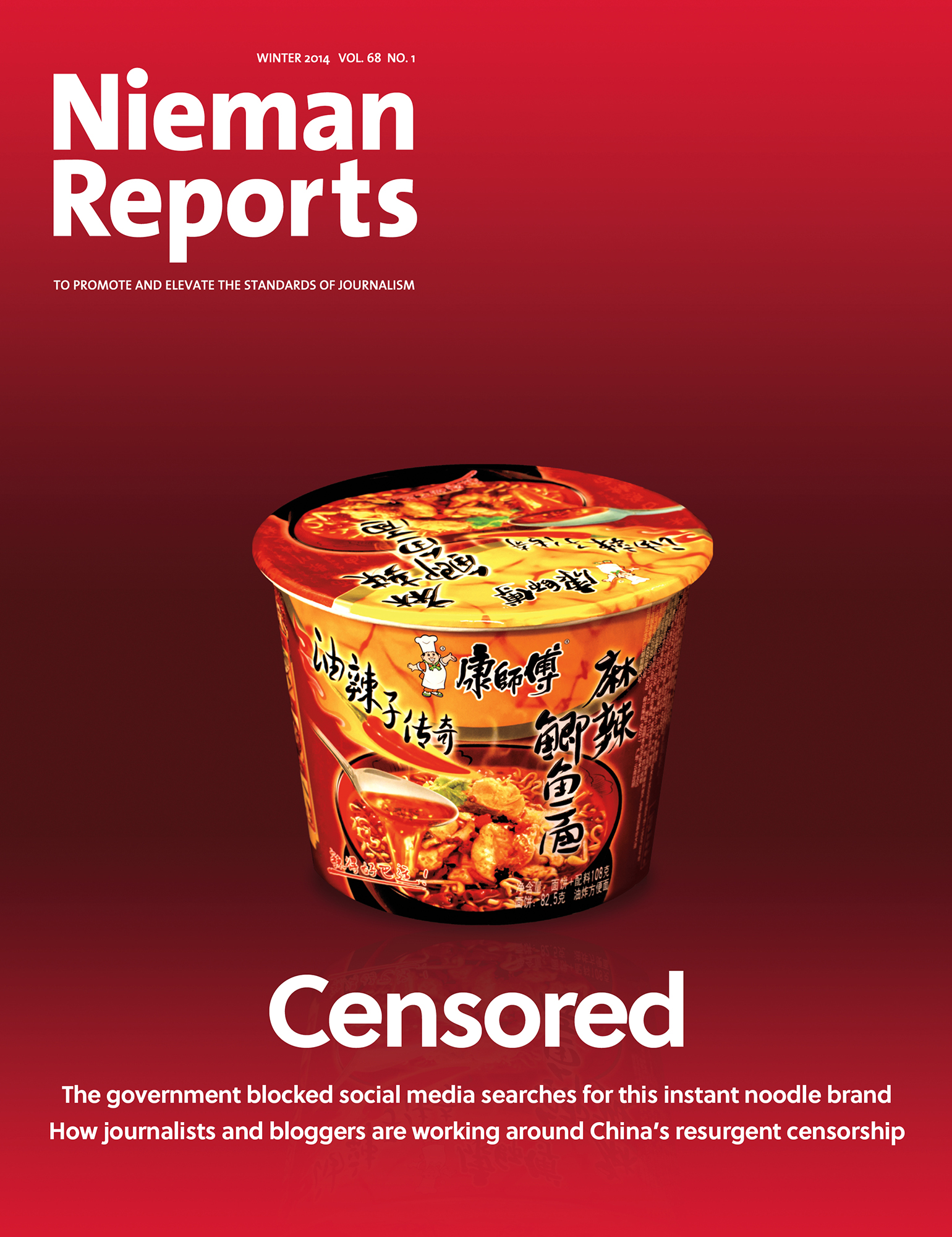

China, the subject of this issue’s cover story, sent its first Nieman Fellow to Harvard in 1981. Since then, 23 more have followed. The story of their work is also the story of a changing China and, most recently, of journalists who face the same technological and commercial disruptions redefining news in the West. Layer this with the threat of repressive government actions for reporting deemed dangerous or simply inconvenient and the applications from China reflect a particular sort of longing.

“I have to admit that sometimes I feel tu long fa shu, or ‘lacking the skill to kill the dragon,’ ” one Chinese applicant wrote us.

During one applicant interview, a passionate and gifted Chinese reporter began describing his hopes for his career “if” he remained a journalist. We were taken aback. “Why if?” I asked. He explained the challenge of confronting the censor’s line without crossing it and wasn’t certain how much longer he could stay true to his high standards. He would rather give up journalism, he said, than debase his reporting or pull a punch.

One senior editor put it this way in a letter of recommendation for the reporter: “Many newspapers humiliate themselves first before they are humiliated by the government.”

Hu Shuli, the editor in chief of China’s Caixin Media Co. and winner of Nieman’s Louis M. Lyons Award for Conscience and Integrity in Journalism, writes in this issue about a particularly insidious form of media debasement: “rent-seeking,” the taking of bribes in exchange for writing stories. It’s a bitter fruit, she says, of China’s distinct media landscape.

“The problem is, in China’s peculiar political and media environment, where some media companies are government-linked, excessive interference and an absence of supervision co-exist, making it easier for people to succumb to temptation, be it commercial or political,” she writes. “Thus, some media firms smear companies that refuse to place ads with them, while others are happy to sell themselves as public relations tools. Such practices are no secret within the industry; some even brag about them.”

While journalism in China is attracting a level of attention on scale with the country’s growth as a world power, the challenges there are replicated across the globe in countries less scrutinized by American media. Chronicled in Nieman applications, the hardships and yearnings transcend geography and merge into a remarkably coherent and seemingly universal journalistic language.

In one application, a reporter from the Middle East describes a courageous editor who resisted government pressure to fire him following an exposé that angered authorities. His response yokes him to Chinese journalists he has never met: he published another series of stories revealing government malfeasance.

His goal? To be “unsilenceable,” he wrote us.

An ocean away, a young blogger in a country with state-run media and few press freedoms types her own application. Her frustrations would be familiar to other international journalists, as would her desire for journalism to help inform and shape her country’s future.

She has asked a friend for advice and he has told her about Nieman—”the best opportunity in the world for any journalist,” he has said. “The people who go there want to change the world.”

“I want to be in a place,” she wrote in this season of dreams, “where people go to change the world.”