Coffee table books have a reputation for being self-satisfied bullies, outweighing their competition, demanding pride of place on more than just a nice normal bookshelf, preening with the musculature of their glossy production values. So when one comes along that takes true artistic advantage of the format and uses its heft for something else beyond showing off, it is a cause for celebration. This is the case with “The Oxford Project,” a book of photographs by Peter Feldstein with text by Stephen G. Bloom, who put the poundage to good effect, creating a steady headlong momentum and a compelling narrative arc, so much so that by the final page you feel as if you have both read a novel and seen a movie simultaneously.

The concept behind the book is simple. Move to a small town because that is where you can afford studio space in two dilapidated storefronts and set up shop. “For me,” writes Feldstein, “Oxford was exotic, mysterious and strange. Even though I was an artist, a college professor, and a New York Jew, almost everyone in town welcomed me.”

As a child, Feldstein coped with his anxiety by being a compulsive counter, and the idea to take photos of everyone in Oxford had its roots in that tic.

What did the residents get in return? They got to be the subjects of an exhibit for everyone else in town to see during a brief interval of glory and then they got to be negatives put into dusty storage while time marched on.

Two Decades Later

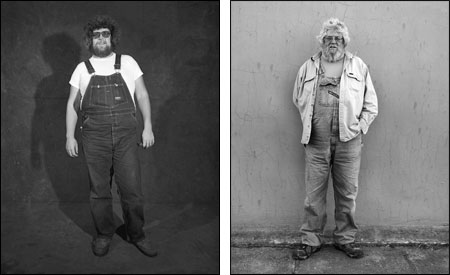

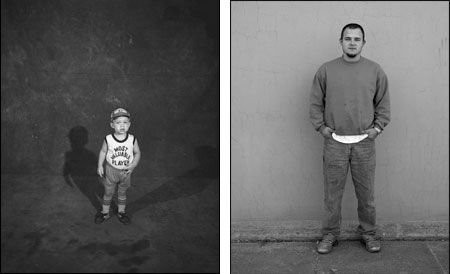

More than 20 years later, Feldstein revisited as many of his original subjects as possible. Rolls of flesh have intruded, hair has disappeared, the sweet unfinished faces of little children and teens have either hardened or blossomed into their adult features. A good number of citizens of Oxford, Iowa, a small town about 16 miles from Iowa City, have either moved away or died. Many of those who remain posed once more, often tilting their heads or placing their hands in an almost eerie unconscious replication of gestures from years gone by, but this time words are added to the mix thanks to interviews conducted by Bloom, who took what the townspeople said and “freeze-dried” (his term) their reflections into concise and memorable set pieces that in their everyday rhythms verge on a kind of found poetry.

Oxford has remained amazingly stable in the time that this project has taken place. In 1984, there were 693 residents (670 of whom were photographed), mostly Caucasian and bohemian, with 12 who identified as minorities. Catholic and Lutheran are and were the predominant religious denominations. Of the adults, married couples outnumbered those who are single, widowed, separated and divorced combined in both time frames. There were and are more Democrats than Republicans. Today there are 705 residents.

A Photographer’s Note slipped in at the end of the book gives a pithy description of the process, a boon to anyone interested in the more technical aspects:

The 1984 photographs were taken with a 4” by 5” Speed Graphic and printed on Kodak Tri-X sheet film. I used two 1000-watt quartz lights and a tarp borrowed from a local construction company as the backdrop. I processed the film with a developing tank that sat in a tub of water. Every now and then I’d check the temperature of the water, which kept rising in the summer heat, and throw in handfuls [of] ice cubes to cool it down; the resulting prints were very uneven.

When I put the negatives away in 1985, I had no intention of ever using them again, and gave little thought to their storage conditions. When I removed them 22 years later, I found some were scratched and terribly dirty. Mixing each image took many hours, from scan to finish.

The current photographs were taken with a 12.8 mexapixel Canon 5D, outdoors in natural light, against a blank wall. From the time I made the first exposure in 2006 to the last in 2008, the wall developed signs of stress. Cracks appeared and worsened, the paint faded, and a bad hailstorm left marks and streaks that are visible in some of the prints.

The book has a hologram on the cover, of a boy and the man he grew into. The black and white photos vary from full-page presentations to collages of many residents. Some pages fold out to yield even more images. There are frequent breathers built into the presentation: double truck establishing images of the town, its cemetery, a still life of a desk, the town’s most popular watering hall, a main artery buttered by snow. Near the end we get a full-page map.

The Reader’s Experience

As a reader you are constantly balancing what you hear with what you see.

The men who served in wars still nurse all kinds of terrible wounds and memories. A gunner on a warship in the Tachen Islands says, “The things I saw would set most people into orbit.” The old guys, the ones who are now dying out, have a disproportionate tendency to go by the nickname Bud. Most people work, as a porter at J.C. Penney, teaching, selling insurance, at the Ford dealership, for Roads as the guy who drives around at 2 a.m. and gets to decide about whether to call out the snowplows, as a secretary at Amana Refrigeration.

One man is a plumber and, in his off time, he works as a diver for the county: “I dive for drowning victims, hunting accidents, snowmobiles that go through the ice. It’s black down there, and you’re crawling through logs. I’ve probably pulled out 20 bodies since ’73.”

Farming accidents are not infrequent and the most likely source of amputations. The two biggest thwarted ambitions appear to be the failure to drive a semi or to have gone to college, but most people are happy enough: “All a guy needs is to get married, have a house, guns, a fishing boat, and a bow and arrows,” reports one relatively contented citizen. They are proud, of being the boy who won the Johnson County Spelling Bee in 1939 or of having been clinically dead four times or of doing a good job earning seven hundred a month on the side picking up roadkill. People like to eat Red Waldorf cake and kolaches (a Czech pastry) and sliced deer meat in cream of mushroom soup. The men, especially, favor hats, and most are proud to carry pliers and pocketknives. Sneakers are popular, also clothing with the word “Iowa” on it. The ladies sometimes hoard recipes (such as the one for no-fail crust), and people like activities that create verbs from what used to be nouns: They scrapbook and they mushroom. Target hunting is popular because it is “something you don’t have to feel too bad about.” In the winter the men ice fish, for crappies, bluegills, walleyes and northerners.

Travel is not a big goal, except maybe to Alaska where there is alleged to be a lot of nature. “One state I don’t ever care to go to is California,” says one resident. “I can do without earthquakes. New York is another state that doesn’t impress me. Who wants a city with bombs being dropped on it?” They favor a card game named euchre, and they often name their children with the same first letter (Michael, Mary, Mart, Mindy, Morgan and Matthew.) They know that the doughnut lady, Kathy Tandy, who makes more than 11 dozen every day and is now down to 260 pounds from a high of 432, seems not to mind that at one point everyone in town knew she had to be weighed on a livestock scale.

They know the sad stories of each other’s early lives, such as what happened to Brianne Leckness: “My mom left me at a church when I was three. She used to travel with the carnival, and the carnival ended up going broke in Iowa. When my mom and my stepfather had a hard day, they’d take it out on me. So she left me at this church with our dog Freddy. She pinned a note to my shirt that said, ‘Please take care of her. We can’t any longer.’”

Gays exist, at least on the edges. One woman says of her son, Johnny, that he used to be a jeweler in Houston. He came back home after he was diagnosed with HIV in the late 80’s: “When the kids were little, I wasn’t home a lot (I had two jobs, sometimes three), and Johnny took over the responsibilities. He liked to bake and cook, and he liked nice clothes. I kinda felt it coming. I accept it, but his father can’t.”

Hippies exist, too: families that grew up in panel trucks and named their children Unity and Cayenne.

Some people in Oxford seem to relish the limitations of their homogeneity: “I’ve never talked to a black person in my life. I don’t have any trust with them. There’s two kinds of blacks. There’s the no-good kind, and then there’s the white black. I don’t agree with how they talk, the jibber-jabber. I don’t like the baggy, hip-hop clothes.”

Yet one of the few people of color, a young woman named Ebony, says her mixed heritage has never caused any problems, and she does not think about it much: “If someone asks, I just tell them what I am. No one has treated me badly. At least nothing I can remember.”

For the most part the citizens of Oxford accept the cycles of life, although once in a while someone likes to tempt fate. Kevin Hackathorn tells Bloom: “I like my Harley, it’s a Softail Classic. They run about $22,500. I don’t wear a helmet. I like the freedom. If you’re involved in a bad accident, it’s pretty much over anyway. The only difference is an open or closed casket.”

They suffer unbearable losses, little children and grown ones to cancer and accidents and husbands and wives to the more ordinary oppressions of time. Some who suffer bounce back. A man who lost his infant daughter due to “placental abruption,” which he says is “a Latin term for Bad Fucking Luck,” is grateful that during her six days of life in a hospital she met all of her extended family: “There’d be eight, 10 people singing to her. We took her outside. I wanted her to feel the breeze and hear the birds and other children playing.” Later: “Charisma and I now have a year-and-half-old daughter. Her name is Isabella Noel, which means Beautiful Gift. Are we better parents after losing Brit? Absolutely. Smelling the smells, tasting the tastes, knowing it could be gone—it changes you. Life is a pretty thin string.”

The people of Oxford believe in regeneration, and they believe, many of them, in Jesus. They also believe in love. A preschool teacher says, “I totally believe my soul mate is out there, but he’s hiding.”

What we have in this spellbinding and ambitious and eccentric volume is “Our Town” and “Spoon River Anthology” updated and revivified. We also have journalism, in words and in images, at its heart-stopping best and its most poignant.

Madeleine Blais, a 1986 Nieman Fellow, is a professor in the Journalism Program of the University of Massachusetts, Amherst. She was a reporter at The Boston Globe, the Trenton Times, and Tropic Magazine of The Miami Herald. She won the Pulitzer Prize for Feature Writing while at the Herald. Her books include “In These Girls, Hope Is a Muscle” and “Uphill Walkers: Memoir of a Family.”

Kevin Somerville (born 1949), then and now.

Jay Stratton (born 1982), then and now.

Brianne Leckness (born 1980), birth name Bobby Jo Kirkwood, with her dog, Freddy, then and now.