Brooke Kroeger’s upcoming book is about undercover journalism done in the public interest, and a Chicago Daily Times madhouse exposé is part of a free online database that she created and will launch with her book’s publication.

Too often, journalists draw blanks when they are asked in faculty search interviews to expound on their big ideas. Had I still been in the hurricane of daily journalism when I interviewed for a full-time academic position, I might have done the same. As things turned out, when I answered an advertisement on a lark in 1998, I had the distinct but unplanned advantage of having left a newsroom a full decade earlier. By then, my biography about the adventurous, undercover journalist Nellie Bly had been in print for four years and I had just submitted the manuscript for a biography of the American novelist Fannie Hurst. The books certainly helped me get the job.

Teaching at New York University (NYU) turned out to be just as rewarding as I had hoped, but it quickly became clear that the center panel of the academic triptych—alongside teaching and service—is scholarship. So a new book got under way. "Passing: When People Can’t Be Who They Are" explores why people of good purpose would falsify the way they present themselves to others. My fourth book comes out in 2012. "Undercover Reporting: The Truth About Deception" argues in favor of the controversial journalistic practice in its title.

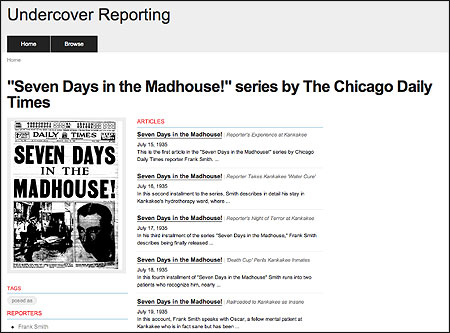

In a deep bow to our digital times, the book has a companion—a free online database created in partnership with NYU’s Elmer Holmes Bobst Library. Together they exhume from the microfilm burial ground nearly 200 years worth of great but forgotten high-impact undercover journalism committed in the public interest. My hope—and intent—is to broaden the database beyond its clear U.S.-bias once it goes live at undercoverreporting.org with the book’s publication in 2012.

I admire the many journalists who manage to research and write books while doing stories on constant deadline in someone else’s keep. But I could never have carved out the space to do books that way. The 12 years I spent being wire service crazy—four years in Chicago, eight in the maelstrom of foreign bureaus—and then two more years at a daily newspaper in New York City took all the energy and focus I had, especially given the competition from a family at home. No doubt becoming a freelancer made the two biographies possible, shielded by commercial advances and the largesse of a husband willing to let me sate a desire that took hold as I headed into my 40’s.

Book Boosters

The university has been just as magnanimous a patron but a far more exacting one. Teaching allows tighter control over time than daily journalism does, but student needs are too consuming ever to be treated as a sideshow. It took only one three-hour-and-forty-minute class for me to grasp that teaching has an unexpectedly exhausting performance dimension, too.

No complaint, however. In the university, the onus to produce new knowledge is not a thing apart; it’s built into the brief. During the years I was researching and writing "Passing," the terms of my full-time university appointment also provided three 12-week summer breaks and three five-week winter breaks. In the scope of my book writing time, this was a virtual year.

"Undercover" also took nearly four years to complete but under more encumbered circumstances. In 2005, I became chairwoman of NYU’s school-sized Department of Journalism and then, in 2008, founding director of its Arthur L. Carter Journalism Institute, which are effectively the same entity. Given the demands that the tumult in our industry have brought on j-schools in these years, let’s just say it’s been a wire service crazy time. I also continued to teach—one course a term instead of two—and created the graduate Global and Joint Program Studies, which I also direct. Gone were those coveted vacation breaks.

Looking back, I know that a major spur to finishing my last book with so much else going on was the shame I felt, as any self-respecting tenured professor should, for not having managed to write for publication during my first two years as chair.

Luckily, I happened on two great expediters. One was the sudden surge in the online availability of documentary material. In the years between the publication of "Passing" and the start of research for "Undercover Reporting," dozens, but by no means all, of the documents I needed became available and searchable online, arriving free or through subscription-based digital repositories, many of which NYU provides through Bobst, which is another huge research advantage of academic affiliation. Even more material now comes glitch-free, in ways it formerly did not, as e-mail attachments, either as a courtesy from individuals with personal archives or via the precious services of interlibrary loan.

In fact, I retrieved much of the primary material that undergirds "Undercover Reporting"—works of journalism in every medium going as far back as 1822—in pajamas. The other big helper was when I figured out that waking up at 4 a.m. turns one workday into two.

Body of Work

One of the things the tenure and promotion process does is oblige professors to articulate the cohesion in their body of work. My first two books made this easy. The research I had done for Bly (1864-1922) had actually led me to Hurst (1885-1968), an ideal chronological successor. In the overlapping lives of these two extraordinary but largely forgotten women writers, I began to ferret out why a highly redundant women’s movement came into being in the 1960’s when so much of this same feminist ground—the lives of women entering the workforce in Bly’s day were pure testament—already had been trod between 1880 and 1920. In figuring out what caused the amnesia and then the re-run, Hurst’s life, work and social circles provided persuasive clues.

The connective tissue of the two books I’ve written while teaching journalism—"Passing" and "Undercover Reporting"—is the exploration of how deception can be used for good purpose. Yet I had to ask myself whether these two books cohere with the earlier ones in some vast, incisive scholarly plan. Although I didn’t consciously plan it, they do.

The thread I pulled from Hurst was her classic 1933 women’s weeper, "Imitation of Life," the ultimate black passing for white melodrama, which was the inspiration for wondering if people still had cause to "pass" 70 years later, and if it was or was not a bad thing. And who better than the iconoclastic Bly to summon the larger questions inspired by the potency and pitfalls of the passing that is at the heart of reporting undercover?

The only big change for me this time is that the publisher and the premise are academic like, gulp, me. The journalist, however, still rules. The book is jargon-free.

Brooke Kroeger, a professor at New York University’s Arthur L. Carter Journalism Institute, served as chair of the Department of Journalism from 2005 to 2011. She is the author of four nonfiction books, including "Undercover Reporting: The Truth About Deception," to be published by Northwestern University Press in 2012. Her website is http://brookekroeger.com.