Cecil Arnim, Jr., a veterinarian in Uvalde, Texas, holds a container of anthrax vaccine. November 2001. Photo by Eric Gay/Courtesy of The Associated Press.

What transpired between journalists and sources during past disasters and crises — such as the 2001 anthrax attacks — can illuminate challenges confronting the press as it seeks reliable information from experts. Some lessons are shared by a journalist who retraced what happened and points to what can be learned from what didn’t work well before.

Bruce Shapiro, Executive Director, Dart Center for Journalism and Trauma and Contributing Editor, The Nation

I want to start with a perhaps heretical suggestion: The “news media” — Capital T, capital N, capital M, the great monolith called the news media — doesn’t exist. All of you who are journalists know this. We are a fractious, combative, disorganized tribe of newsgatherers. And when we’re talking about a great crisis, we really need to break this down into three components.

There are journalists — people who are witnesses, mediators of information, skeptics, questioners and storytellers — making constant choices about information, credibility of sources, and shape of narrative at a time of crisis. Institutional media also exists, and it consists of news organizations as workplaces, as trusted vehicles for communication, and conveners of discussion among leaders. And finally, the media is also news consumers. Those from New Orleans or Biloxi, Mississippi know that their consumers in the great time of crisis represented by Hurricane Katrina saw their news organizations as part of their mechanism for survival and as, indeed, part of themselves. We know this casually day-to-day. Write something that annoys readers, viewers or listeners and they write back. They respond because people have a proprietary investment in their trusted media. But in times of crisis, the identity of news consumers with their trusted media is just as important as the role of reporters and just as important as the role of the institutional media.

It’s very important to remember these components. Remember also that neither reporters nor news consumers are empty vessels into which either experts or the media can pour knowledge. People greet the news with critical experience. They greet it with desires for altruism and with desires for a rational response to information.

Chris Oronzio, then manager of in-plant support at the United States Postal Service North Metro Processing and Distribution Center in Duluth, Georgia explains how the new Biohazard Detection System will detect anthrax in the mail. September 2004. Photo by Craig Moore/Gwinnett Daily Post/Courtesy of The Associated Press.

Patricia Thomas, Knight Chair in Health and Medical Journalism, Grady College of Journalism and Mass Communication, University of Georgia

What anthrax teaches in a changed world.

I want to take you back to the anthrax attacks of 2001 and an analysis I was asked by The Century Foundation to do of how the news was managed and reported during the time of those attacks. During seven weeks and in seven states, there were 22 cases of anthrax and five deaths, and 32,000 people put on antibiotics for 10 days and another 10,000 put on antibiotics for 60 days. It was the third most closely followed story of 2001, topped only by the attacks of September 11th and the war in Afghanistan. During the final three months of 2001, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) received 12,000 print mentions and a lot of broadcast time. Based on what I learned, I’m also here to tell you that I’m a lot less confident than the health organization communicators who spoke here seem to be that reporters are going to get what they need from government experts when the proverbial substance hits the proverbial spinning blade.

What I learned in doing this report was that reporters faced an evolving set of challenges that began before they even realized there were any challenges. What they didn’t know was that on September 11th the rules of engagement between government spokespersons and reporters changed because the Federal Emergency Response Plan was set in motion that day. That meant that communications were officially centralized at the level of the cabinet secretary; so from that moment on Health and Human Services Secretary Tommy Thompson was in charge of relations with the press, and he had a little trouble with how anthrax is transmitted.

In the wake of 9/11, the CDC told me they got 358 bioterrorism-related media inquiries during late September and early October. They forwarded those messages to Thompson’s press operation in Washington where there was no record of whatever happened to them. Reporters whom I interviewed in 2002 said no one ever called them back. So reporters wrote stories by leaning on other sources. They used people who had been in previous administrations, scientists who had served on Institute of Medicine panels, and other expert bodies. They did the best they could.

Government response involving anthrax was hobbled in two different ways. The Bush administration insisted that it would be desirable and possible to speak with one voice during the crisis, pretty much ignoring the impossibility of pulling this off given how traumatized, exercised and hypersensitive the citizenry was about their health and that of their children as mail was coming into their homes. Fortunately, with the passage of time, we are now more likely to hear public information officers talk about a “many voice-one message” approach.

RELATED WEB LINKS

· “The Anthrax Attacks” Century Foundation Report

– tcf.org

· Patricia Thomas’s article in Nieman Reports (pdf)

– nieman.harvard.eduThere are also inherent limitations in the CDC’s communications setup. The central communications office there has always had a split mission. It’s half a health education enterprise with a lot of PhD’s who specialize in the packaging of health messages and behavior change campaigns, things we approve of like quitting smoking and eating a healthier diet. The other half of that team is the science and media relations. In late 2001 there were 10 people who were qualified and authorized to speak to reporters. But, of course, that authority had been shipped off to Washington, and the leadership at the time didn’t come from a news background and wasn’t really comfortable talking with the press, either.

Official information during the height of the anthrax crisis was pretty scarce. The CDC press office was understaffed on an ordinary day, and it lost its authority. During the first two weeks of the anthrax crisis — beginning on October 3rd — they logged 2,500 calls into their system. Many were referred to Washington where they once again disappeared into the abyss. And this is no joke. The CDC cooperated fully with me, giving me copies of phone logs, showing me exact graphing of the patterns of calls, but that was not true in Washington. They didn’t seem to know or want to say what happened.

Very persistent reporters called the epidemic intelligence service teams at various sites throughout the world. These teams now have a press officer attached, so these reporters would track down the press officer in the field. But they, in turn, would bounce the call back to the CDC office in Atlanta where it was going to get bounced to Washington, so they weren’t exactly getting calls back, either. And, in fact, the reporters I interviewed said they never got any calls back.

RELATED ARTICLE

“Communicating News of an Outbreak”During the second half of October, the situation became even worse. On peak days the CDC press office was logging 500 calls a day. Reporter friends of mine who now work in press communications tell me that a really, really good public information officer can handle about 20 reporter inquiries a day. At this point, the CDC folks realized that they had to do something, so they started bringing more staff on board; they started calling back more A-list reporters, although I think small publications were pretty much still in trouble.

So what did reporters do during all this communications meltdown? They dutifully went to those press conferences in Washington with Tommy Thompson and Homeland Security Secretary Tom Ridge, and once there was anthrax on Capitol Hill, they were trampled by the senators and representatives rushing to the microphone there. Reporters used PubMed and other sources to seek out a lot of academic experts on anthrax. But the trouble was that those experts were much in demand from the FBI, which especially needed molecular biologists familiar with anthrax to help them test samples and figure out what the genome of the virus was. These people then quickly became inaccessible because they were working for the government now.

Particularly on the broadcast side, with a lot of airtime to fill, something needs to go up there. So that’s where we began to see a lot of second-tier, and even bogus, experts, who were just really, really, really eager to get on television and sell space suits or special potions that would kill the spores. And, of course, as reporters, we did what we do when we’re really, really desperate, we started to read. Fortunately, there was a lot of published literature, so people could do that for a while. Then, of course, we get mad when we’re treated like this, so after a while, the failure of the government communications effort became the story, and many newspapers excoriated CDC for bungling communications.

So you might ask yourself, if information was so limited and communication was so poor, what was the consequence? The answer is there were almost no consequences. Only one real study was done — that one by the Harvard School of Public Health — to measure the public understanding of anthrax and of the risks that it actually posed to them and their families. Remember, this was the third-biggest story of the year, and the study found that the public’s factual knowledge about anthrax was good. More than three-quarters of the people surveyed knew that the cutaneous form wasn’t really serious and that the inhalational form was the kind that would probably kill you. They knew that the disease was not passed person-to-person. They understood that, so they weren’t shunning people. And they knew that fewer than 10 people had died. One thing that was learned in this study is that when people are threatened by some kind of health thing, they want to hear from real doctors and real public health experts. And what I concluded from this was that the rumors of panic were vastly overstated. There really wasn’t much panic.

So that brings me to the interesting question of what about the next time? Five years have passed. The news world and the world of public health have both changed. A lot of journalists are confronting layoffs, buy-outs and changed ownership, and there has also been the rising power of bloggers. At least three times in the past six months, The New York Times’s articles about pandemic flu have responded to specific claims made by what they call “Internet flu watchers.” Giving national ink to people who we once would have considered gadflies is not new, but it is a rising phenomenon. Blogs were a factor during the anthrax episode, but they’re going to be so much more important in a case of pandemic flu, with a huge, huge impact.

Another thing that we really have barely touched on at this conference is the tremendous growth of ethnic media outlets. Research conducted by New America Media indicates that some 51 million U.S. adults get news from ethnic, non-English news outlets, and that these publications and broadcast stations are the main source of news for 13 percent of Americans today. In November I heard Sandy Close, who is the head of New America Media, present the statistics to a national conference for state and local public health public information officers. They seemed shocked at the idea that the ethnic media has become so huge. When the state officers made presentations at their own national professional meetings about pandemic flu, they patted themselves on the back for translating some of their handouts into Spanish.

Such an effort is not going to be enough in this polyglot nation that we have become. Ethnic publications need to be better represented at conferences like this one. They need to be on the alert list. They need to have their calls returned by public health agencies in the same way journalists do who work for major dailies. Right now reporters for ethnic media do not get treated the same. So we are putting communities at huge risk by narrowing who we distribute the message to.

Finally, I will offer a few comments about the changes in the public health establishment that will affect how public health messages are communicated to us and to our audiences. In the wake of 9/11 and the anthrax bioterrorism, there has been a five billion dollar windfall for public health workforce preparedness and training. Originally, this was all focused on bioterrorism, but that’s been repurposed as time has passed. This infusion of money offers both good and bad news. The new money has helped bring public health technology into the 20th century, if not the 21st. When all of this happened, they were still reporting these diseases on paper; there weren’t radio systems that enabled health departments and cops to talk with one another, or Web-based alert systems, or secure cable connections between state and local health departments. All of these are long overdue advances that increase the capacity for effective communication among agencies that will have to work together in the next crisis.

The bioterrorism windfall has also added epidemiologists, laboratory workers, emergency response coordinators, and public information officers to state and local health departments, all of whom were originally assigned to bioterrorism. Many of these folk have been repurposed and are just about working full-time on pandemic flu now.

Why is this bad? Paradoxically this federal infusion of tax dollars may weaken public health infrastructure in the long run, because when federal dollars pay for personnel, then state and local agencies drop these positions from their budgets. But what Congress gives it can take back. In the July/August issue of Health Affairs there is a really interesting study about public health work force. The size of the nation’s public health work force increased gradually from 1980 to 2003, but it’s now taken a little dive downward. The researchers predict that it will shrink more when bioterrorism is pushed aside by some new national priority and they observe a national shortage of skilled, experienced health workers and that public agencies have been very bad at setting up incentive systems that retain their best and get rid of their worst.

So where does that leave the flow of health information between agencies and reporters? A study by Rand researchers finds while there have been more press officers hired, the new emergency managers come from hierarchical organizations — the military, law enforcement, or emergency response agencies — and they are people who are used to taking command. These are take-charge kind of people. From what I’ve seen in working on local pandemic flu planning in Georgia is that in a crisis the public health information officers will be taking their orders from the big guys with the side arms. During the recent national conference of state health public information officers, an administrator for the New York State Department cited the clash of corporate cultures, specifically law enforcement and public health, as one of her leading concerns if pandemic flu strikes. I also question whether the CDC — which has been inadequately funded throughout its history — has within its communications operation the surge capacity to handle the thousands of media calls it would receive if pandemic flu arrives, or if there is another Katrina, or if there is another bioterrorism strike.

If the next public health crisis strikes within the next two years, my bet is that administration officials in Washington will once again circle the wagons, clamp down on what CDC can say, and strive to speak with one voice. This strategy did not serve the public well five years ago, and I don’t think that it will work any better the next time.

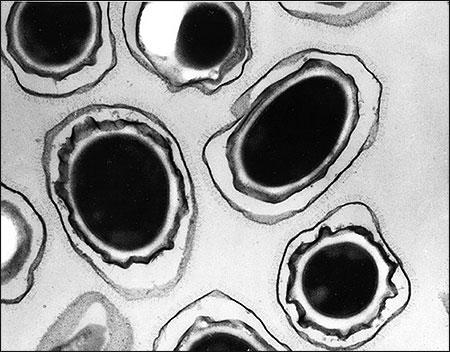

Bacillus anthraces spores are seen in this photomicrograph from the U.S. Department of Defense anthrax information Web site. Photo courtesy The Associated Press Photo/Ho, Anthrax Vaccine Immunization Program.

Ford Rowan, Former NBC News National Security Correspondent and Author

Ask ethical questions, in particular about what are the standards for triage. If a child is taken into the medical processing center and the parents are told, “Get in that line over there,” it probably won’t take much time for them to realize this is the line where the medical people let you either get well or die. The other line got the first responders, and that’s where the mayor’s family is standing and they’re getting something, might be Tamiflu or whatever. Families are going to wonder what the hell is going on, and they are going to be upset. I would be if I don’t know in advance what the system is and if it hasn’t been agreed upon in advance by the religious, civic and other leaders in the community. I’m going to be angry as hell.

Such policies and decision-making can and ought to be talked about in advance. The ethical issues are enormous, and they’re not being discussed, debated and decided in a consensual way. I worry about this because the experts get together and talk about it. Like yesterday I heard researchers who have studied policy implications tell us that the closing of border crossings is “a stupid thing.” I translated that as “Shit! Someone in the White House is going to close the borders!”

But we can prevent stupidity. We can prevent stupidity from reining supreme if we do things today to think through these policies. Journalists have an enormous role to play in that, and they can do it through “let the chips fall where they may” reporting. They can do it in an “I’m going to help my community” mode, and they can do it in a muckraking mode. Any of those three ways will be productive. It will get people thinking about how we can become a more resilient community.

In a discussion period that followed, Thom Schwarz, editorial director of the American Journal of Nursing, who was a triage nurse for 25 years, spoke out of his experiences, and then a conversation ensued about the most reliable sources of information during a pandemic.

Thom Schwarz: I stepped out at 3:00 one afternoon to do the kind of triaging that you were speaking about, and there was a sea of people there because it was a very busy day. I said “Please, one at a time, if you could just quickly tell me what’s going on.” This woman in front of me is there with a child who had a head wound, and the kid was screaming, and his wound was bleeding. It was terrible. I said “Okay. Thank you very much.” And in the back of the room, there was this little old man, and after I spoke with him I said, “Okay, you come with me,” and I told the woman I’d be back out very soon. The woman freaked out and said, “Well, what are you going to do?” The man went into the back to be taken care of. I took a bandage and put it on the little kid’s head, then I sat down and I looked at the wound, and I said very calmly, “Your son’s going to be okay. He has a head wound, and they really bleed a lot.” The kid listened to me, and the wound stopped bleeding. In the meantime, the guy had coded in the back, and I explained to the lady, “Your son’s going to be okay, but that gentleman probably isn’t going to make it.” He didn’t make it.

I’m just somebody who’s explaining in very simple language what was going on. Who do you trust about anthrax? Nurses didn’t make your list. But I’d suggest to you — and I was a newspaper reporter before I became a nurse — that Rolodexes should be filled with names of nurse experts, epidemiologists and public health nurses and infectious disease nurses, because doctors will be doing the work, and the nurses will be available to explain in language that your readers will understand what’s going on because they’ll understand what’s going on.

Michael Osterholm, Director, Center for Infectious Disease Research and Policy and Member of the National Science Advisory Board on Biosecurity: I’d like to offer an alternative opinion on that issue. Having spent 30 years on the frontlines of public health in Minnesota, some of our biggest problems were local nurses and doctors who thought they were expert on a topic. When they were being asked something on a very timely manner on outbreak and so forth, they gave out bad information because they weren’t experienced to deal with the media. They felt they had good media answers and, as such, they answered in ways that actually were wrong. The point is, you have to ask the expert for what they’re expert for. If you’re asking a local nurse about what’s going on in their emergency room, he or she is very expert about that. If you’re asking them about should, in fact, this community be vaccinated for something that has many nuances to it, that person doesn’t have the experience as an expert. The key message is to get the right expert for the right question at the right time.

Thomas: Technology is our friend here, too. In the wake of anthrax, CDC did create a much more sophisticated command and communications center. At the time anthrax hit, they couldn’t do a television news conference on the CDC campus. With this briefing room and the capacity for telephone briefings with hundreds of reporters around the country (which began to work late in the anthrax crisis), the situation improves. But if the power grid goes down, we’re left with little local core groups at local hospitals, and the public health doctors trying to work out a system. If we could have a satellite phone system, there’d be a way to reach newspaper reporters sequestered in their own homes putting out only an online version of the news. How can those doctors best talk to those reporters? That’s the level of discussion that’s going on, and if doctors can get access to something that resembled accurate information online that would help them.