Margaret Hastings was one of three survivors of a plane crash in Dutch New Guinea in World War II. She held the rank of corporal but she is wearing a jacket with sergeant’s stripes that was dropped in. Photo by C. Earl Walter, Jr.

The great director Robert Altman had a stock line whenever people asked him for advice: “Don’t take advice.” With that in mind, I come hesitantly to the task of giving writing advice, knowing that every writer is unique and brings different tools to the job. What I can do, however, is describe some of the experiences I had while researching and writing my recent book, “Lost in Shangri-La: A True Story of Survival, Adventure, and the Most Incredible Rescue Mission of World War II,” in the hope that other writers might find them useful, or at least satisfyingly familiar.

To state the obvious, there’s no book without a book-worthy idea. “Lost in Shangri-La” began for me with a happy accident. I was researching what I thought might be a World War II story that could sustain a book (and my interest) by indulging in one of my favorite research activities: reading newspaper archives. There’s no better way I know to immerse myself in a particular place or time that isn’t my own. From the placement and tone of stories and photos to the prices in the ads, newspapers are to writers of historical nonfiction what tar pits are to archaeologists. Even if I think I know what I’m looking for, I engage in what seems like the time-wasting activity of letting my eyes wander over random headlines, down columns of agate-type classified ads, through impassioned editorials about issues of fleetingly momentous importance. When I’m doubting a project, usually because I’m bored or disappointed by it, I find myself spending unbroken hours feeding my historic newspaper habit.

That was the case with my original World War II idea, which I had begun to realize would make a decent magazine-length story but couldn’t possibly sustain a book, at least not how I was then envisioning it. To me, a book requires not just a great story, but also a theme that fuels the narrative engine. In my oversimplified explanation, my books have been about, respectively, life, death, money, art and war. (I only half-jokingly say that I’m working my way up to sex.) Rather than force myself back to it, I aimlessly scanned through microfilm of dozens of Chicago Tribunes from 1945 when I came upon a headline that read: “Clouds Defeat Hidden Valley Rescue Effort: Glider Snatch Waits on Good Weather.”

Huh? The story described how this valley on the island of Dutch New Guinea, nicknamed “Shangri-La” by United States Army airmen and war correspondents, had become a temporary home to three survivors of a plane crash, one a beautiful woman, and a team of paratroopers who’d volunteered to protect them from the Stone Age natives who lived there. It further explained that the military’s rescue plan involved dropping huge gliders to the valley floor, where, if everything went well, they’d await low-flying planes that would snatch them back into the air—with the survivors and paratroopers aboard.

How, I wondered, was this possible? Not just the gliders and the Stone Age tribesmen, but the very existence of what seemed like an amazing, untold story of World War II. It seemed too good to be true, and having already written a book about the original Ponzi scheme, I was especially wary of anything that fit that description. Yet with a little digging, it became clear that with the exception of a collection of reprinted documents, profile sketches, and short essays, the story had remained virtually unknown and untold at book length.

The next question reflects the deeply held skepticism of all reporters: Does the fact that this story hasn’t been told mean that there’s not enough to tell it? I’ve walked away from more potential ideas than I care to think about because there wasn’t a “critical mass” of sources—documentary and, if recent enough, human—to sustain a nonfiction narrative of something like 100,000 words.

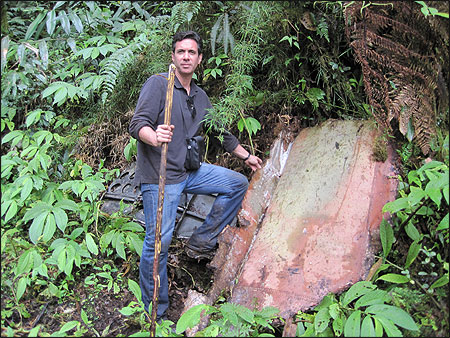

On his visit to “Shangri-La,” Mitchell Zuckoff found wreckage from the plane crash that stranded three members of the American military in a remote valley of Dutch New Guinea. Photo by Buzz Maxey.

Starting With Earl

In this case, after the disappointment of learning that the three survivors had since died, I had the incredible good fortune of finding the leader of the paratrooper rescue team, C. Earl Walter, Jr., living quietly with his memories firmly intact in a retirement home in Oregon. Knowing that he was in his late 80’s, I flew from Boston within days of that discovery.

During the three days we spent together, Walter and I developed the beginnings of a friendship and he gained enough trust to give me a copy of the three-inch-thick scrapbook his late wife had made of this adventure, and even better, the daily journal he kept during the six weeks he spent in “Shangri-La.”

One thing led to another, and soon I found myself in the Tioga County Historical Society building in Owego, New York, where local historian Emma Sedore had meticulously maintained an archive of materials about hometown gal Margaret Hastings, the female survivor. Sedore provided me with a trove of letters, photos, scrapbooks and—miracle of miracles—a typed copy of the 20,000-word diary Hastings kept in the valley.

Over the months to come, I’d find additional photos, scrapbooks, letters, declassified military documents, and lots more, but at that moment I knew this would be a book.

One quick aside: Not everyone agreed.

When I first began to pursue a contract for “Lost in Shangri-La,” I was already committed to write a much different book. It was a good idea for the right person, which wasn’t me. As I wrote in the acknowledgments to “Lost in Shangri-La,” my daughters could tell from my lack of energy and excitement that I was struggling to drag myself to my computer, a telltale sign of a terrible fit. Without going into too many uncomfortable details, the idea had come from an editor for whom I have great respect and affection. I asked him if I could switch ideas but was told that his publishing house wasn’t interested. Knowing that it would mean an end to a professional relationship I cherished, I held my breath and dove into the new idea.

First, though, I dug into savings and returned the largely spent advance for the never-to-be-written-by-me book (plus my agent’s 15 percent fee; I was the one backing out of a contract, not him). Soon after, a second editor I liked also passed on a proposal I wrote for my new idea, which at the time I was calling simply “Shangri-La.” I confess to unsightly sweat stains at this point. Then my agent called and told me he had a perfect fit: Claire Wachtel at HarperCollins loved the idea and wanted to make a preemptive offer before it went to auction. In my selective, self-serving memory, I answered suavely: Tell her to preempt at will and I’ll consider it. In fact, I probably slobbered something like, “Oh, thank God, I’m not ruined.”

From there, I went happily on what I like to call “my nonfiction scavenger hunt,” making long wish lists of people and documents I knew that, if found, would help me tell this story in all its glory. When I make these lists, I know that I won’t be able to find everything. In fact, if I ever found everything I was looking for when writing a work of narrative history, I’d know my list wasn’t ambitious or audacious enough. By shooting for the moon, I might reach the sky. Knowing in advance that I won’t find everything also helps to keep my blood pressure in check.

As a believer in strict nonfiction, in which the work is backed up by exhaustive endnotes—they are my favorite 40 pages of “Lost in Shangri-La”—I have to make peace with the fact that not every question, theory or desire I have will be answered, proved or fulfilled. Sometimes that will mean leaving out something altogether, while other times it will mean keeping faith with readers by making it unmistakably clear when supposition is all I have to go on.

The way I figure it, as a journalist I long ago accepted that omniscience was the province of novelists. The best I could hope for was a relentless pursuit of the truth and transparency about where I succeeded and where I fell short.

There’s a lot more to say about how I approach research and writing books as a journalist-turned-author, but that might risk sounding as though I am giving advice.

Mitchell Zuckoff is a professor of journalism at Boston University and the author of five nonfiction books, including The New York Times bestselling “Lost in Shangri-La: A True Story of Survival, Adventure and the Most Incredible Rescue Mission of World War II.”