Thinking back, I’ve always considered news as a dialogue rather than a monologue. I’ve preferred conversations to speeches. That said, I don’t often hang out on street corners or in neighborhood bars partaking in random conversations about the weather or the Mets. I like my conversations curated.

While it’s easy—and tempting—to think of what’s happening to news as the result of technology, my earliest memories of what we now think of as interactive news and social media reside in a single phone line and a RadioShack answering machine.

This memorable moment took place in 1992 when I was the executive producer of a newsmagazine called "Broadcast: New York," a weekly half-hour solidly reported news show that was syndicated across New York State. Most of the networks were experiencing an explosion of their own newsmagazine shows. One day as we were trying to come up with original stories and new topics, I exploded in frustration in front of my producers: "We’re doing the same damn stories as everyone else. We’re out of original ideas."

Viewers News

That was the day that we purchased what was then a pricey 800 number and went on the air with a new segment. We asked the audience to call in and suggest stories that needed to be covered. If the idea turned out to be good and the lead was solid, we assigned a producer to do the story. Then we used the person’s voice from the call to introduce the segment on air.

It was an immediate hit—so popular that callers often found a busy signal. But they dialed again and again until they got through and could leave their story idea on our cassette recorder. Often, after that week’s program had aired, I would sit alone in the office and listen to the phone machine beep as the callers pitched their ideas. Back in those early days, the sound was mesmerizing.

After this segment had been on the air for a few months, an Associated Press (AP) reporter called to do a story about our new "technology." I was happy to be quoted by the AP, but I told this reporter that our technology was no different from any other station in New York or anywhere in the United States for that matter. All of us had phones; it’s just that we were choosing to answer them when viewers called.

Six months later, technology caught up with us when Sharp Electronics released a camcorder that made it easy for amateurs to record themselves. Sharp loaned us five of them, and we went on the air the next week offering viewers the opportunity to pitch a story, and if selected, we would FedEx them a camcorder for their use.

"Viewers News"—with cameras shipped to viewers—was an overnight sensation. A few months later a producer summoned me to an edit room. We’d been pitched a story from a woman in Syracuse, New York who had silicone breast implants that had ruptured. She’d had blood poisoning and was now deeply debilitated. The producer was screening her raw tape—a tour of her home, a trip to the supermarket, an awkward interview with her husband, and then, the moment I’ll never forget. The last day she had the camera, she woke up and took the camera with her into the bathroom. She set it on the sink, pressed "record," and then unbuttoned her dressing gown.

As we watched, the room fell silent. She had two terrible scars. There was nothing at all sexual about what we were watching. Just terrible scars.

In that instant I knew our world—and our place in it as journalists—would never be the same. With her camera, she had taken us to a place where no journalist was allowed to go. A place so private and personal that if any TV crew had shot those images they would have been guilty of invading her privacy. But she had taken us there. She had opened the door and invited us in to see what had happened to her.

After some discussion with her and our stations, we broadcast her video that Saturday night at 6:30 on NBC stations.

|

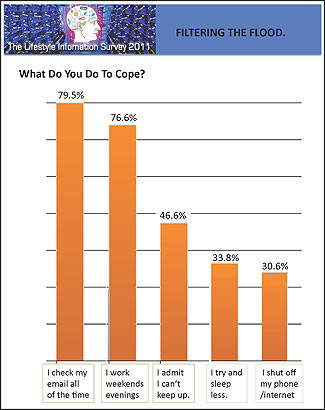

| In the Digital Lifestyle Survey conducted by Magnify.net, almost 80 percent of respondents said they check e-mail “all of the time” to cope with the overload of information. |

Journalist Turned Curator

No longer was I a journalist in the old sense of the word. I’d become a curator—a filter—helping the audience share stories. My role was to decide which stories to put on the air and figure out how to contextualize them. "Viewers News" led to another program that was known as "MTV Unfiltered."

It felt good to play a role in helping viewers emerge from their passive role as TV couch potatoes into an active role as vibrant and prolific creators of content. And today the idea of journalist as curator is front and center, as the tools to make and tell stories are now in the hands of anyone with a cell phone, laptop or desktop computer. The old barriers to entry—the cost of a printing press or a broadcast tower—have evaporated.

Of course, this change doesn’t come without a price. Results of the first annual Digital Lifestyle Survey that we conducted at Magnify.net illuminate the overwhelming amount of data—photographs, texts, messages, chats, videos—that come at consumers. To do the survey, we sent out a Web-based mailing to 10,000 partners, customers and friends in our company database and received 200 responses, mostly from technologists, journalists, entrepreneurs, executives, and professionals.

I found the results stunning. In just 12 months, 65 percent of the respondents said that the data stream coming at them had increased by at least 50 percent. When asked to categorize that data, a majority (72.7 percent) described their data stream as either a "roaring river," a "flood," or a "massive tidal wave."

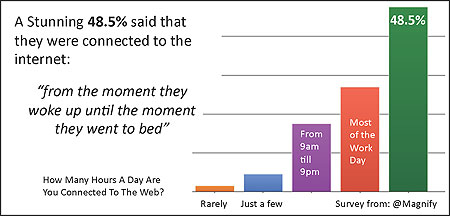

As they take in this surge in information, nearly half (48.5 percent) of the respondents said that they are connected to the Internet "from the moment I wake up until the moment I go to bed." During their waking hours, they struggle under this load of unfiltered input as increasing bandwidth and data abundance has average consumers unable to keep their head above water. More than half (50.3 percent) of those surveyed admitted that "when I’m offline, I am anxious that I’ve missed something." To address their anxiety, 79.5 percent check e-mail all the time, 57.4 percent never turn off their phone, and what I found most disturbing was the revelation that one third of them said that they check e-mail in the middle of the night.

Despite devoting this kind of time and energy to trying to keep up with the data flow, close to half (46.9 percent) agreed with the statement "I am unable to answer all my e-mail," and 62.5 percent agreed with the sentiment "I wish I could filter out the flood of data."

These results paint a stark picture of where we are and where we’re headed. People are clearly overwhelmed by the growing volume and weight of digital content and messaging that they feel compelled to process. As more digital devices and software services proliferate, the amount of data and the speed at which it comes at us will grow exponentially.

Almost half of the respondents to Magnify.net’s Digital Lifestyle Survey reported being connected to the Internet from the time they wake up until they go to bed.

Human Curated Web

Soon this flood will be like an avalanche, burying us if we don’t outrun it. Google’s Eric Schmidt has said that the entire world is creating five exabytes (or five billion gigabytes) of data every two days. That’s equal to all of the information created from the beginning of civilization through 2003.

This simply isn’t sustainable. Try as people might, multitasking or going without sleep is a recipe for disaster. People have reached—and many have surpassed—the limits of their ability to manage data, and this sense of inescapable overload is having an impact on how they relate to family and friends and on their productivity and even their sleep.

Algorithmic solutions like better spam filters, smarter search, and social tools that surface the likes and dislikes of friends will certainly improve things. But the number of connected devices and new social software offerings will create undifferentiated data faster than computers alone can manage.

The solution is not to be found in faster computers or smarter algorithms. The best place to look for a remedy is in the power of the human mind and tapping its capacity to find, sort and contextualize information and ideas. As this happens (and it already is starting) we will think of this time as being the dawn of the human filtered Web—the curated Web.

As a clue to why I am convinced this approach will accelerate as a Web practice, I turn again to the Digital Lifestyle Survey in which a healthy majority (61.3 percent) of the respondents agreed with this concept: "I consider the content I share part of who I am." Skillful sharing of information through channels of community filtering and personal recommendations will fulfill people’s sense of digital identity as content curators. And this leads to a different kind of content consumer, one who will do less surfing of the Web and instead turn to curated content delivered by trusted sources.

Journalism isn’t going to be any less important. In fact, as information gets messier and noisier, those who possess the skills to recognize important stories, find themes, provide context, and explain the significance of pieces of information will be critically important. Instead of reminiscing about the good old days—as we long for the relative quiet and lack of disruption we had then—let’s take what we know how to do as journalists and find the best way to use these skills to tell stories and provide essential information.

There are communities—geographic and otherwise—that are filled with people eager for somebody to play this much-needed role. With curation as the new journalism, it’s time for us to act.

Steven Rosenbaum is an entrepreneur, filmmaker and author of "Curation Nation: How to Win in a World Where Consumers are Creators," published by McGraw-Hill in 2011. He is the CEO of Magnify.net, a real-time video curation engine for publishers, brands and websites.