Think about a “threat to democracy,” and it’s easy to conjure up an image of the U.S. Capitol on Jan. 6, 2021 — the nation’s very seat of government besieged by rioters convinced that the presidential election was rigged.

American democracy teetered on its foundations that day. There was no shortage of coverage of the insurrection, which was historic, dystopian — and because of its powerful visuals and evolving storyline, perfectly suited for the 24-hour news cycle.

While the insurrection was a wake-up call for the nation as a whole, and the profession of reporting in particular, covering it long term isn’t as clear cut as covering a riot. For a responsible free press, guarding democracy is much more akin to “watching a leak,” says Tony Marcano, managing editor of Southern California Public Radio (KPCC) and LAist, which is launching a Civics and Democracy beat. “You have to pay attention, because that leak could turn into a crack that can turn into damage, and the next thing you know, your house is falling down.”

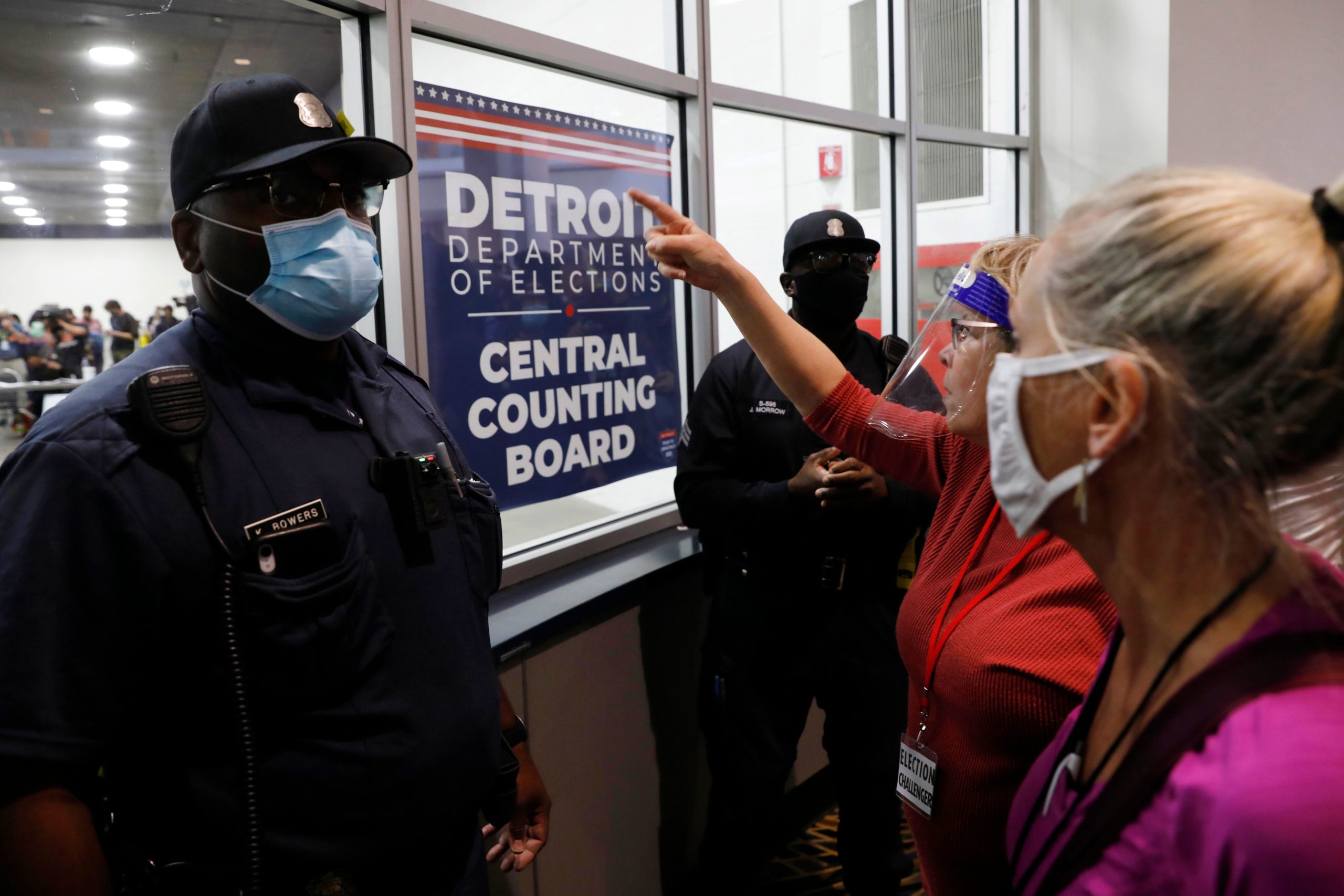

In other words, if the real story of the dangers to the U.S. system of government is to be told, it won’t necessarily be a made-for-T.V. mutiny. Instead, it will happen at local election agencies, statehouses, and school boards. But connecting the dots between what’s going on in disparate communities and menaces on a greater scale takes vigilance — and a willingness to look beyond both traditional horse race coverage and bothsidesism. Simply reporting that certain officials “claim” the 2020 presidential election was rigged by fraudulent voting or voting machine hacks and others “deny” those claims isn’t a framing that goes far enough because there’s no evidence for widespread, game-changing malfeasance. And, giving a platform to former government officials who were actively involved in trying to subvert the 2020 election or covering politicians — like many of the Sunday talk shows do — can normalize their actions.

But news outlets from Washington to California are refocusing their efforts on covering threats to democracy. (It’s also not a strictly American idea: In 2017, the BBC created the Local Democracy Reporting Service to drill down on local and regional seats of power.) This reinvigorated approach to reporting in the wake of the Jan. 6 insurrection can take many forms: In recent months, KUNR Public Radio in Reno, Nevada, went in search of “an innovative Democracy Reporter” to cover the swing state, noting, “This beat is not ‘business as usual’ political reporting.” Boston’s GBH, another public radio station, listed a job earlier this year for “an intrepid reporter to cover Massachusetts politics and policy at the intersection of voters and democracy.” In February, The Washington Post announced it was creating a “democracy desk” to cover threats both at the local and federal levels.

In some ways, the creation of these desks or beats is a formal acknowledgment that the media should see defending democracy as a full-time job, and that the erosion of institutional norms began long before the assault on the Capitol. Sarah Repucci, who co-wrote the report “Freedom in the World 2022: The Global Expansion of Authoritarian Rule” for the nonprofit Freedom House, says the strength of Americans’ access to rights and liberties relative to citizens of other countries started eroding about a decade ago. “The U.S. is still a free country, but it has slipped from being among the best performers in the world and among what we often might think of as our peers, like the U.K. and Germany,” says Repucci. “We are down among countries that you might not think of as much as peers,” such as Romania and Panama. Freedom House bases its scores on 15 civil liberties indicators and 10 political rights indicators including electoral process, functioning of government, and freedom of expression and belief.

The problem is multifaceted, she says: Some of the American decline can be attributed to ongoing systemic discrimination, to the undermining of public trust in elections “due to groundless claims of fraud,” and to the loss of independent news outlets that hold government accountable and educate the electorate. There has been a proliferation of state bills designed to restrict access to mail-in voting or constrict the amount of time the polls can be open. In Georgia, a traditionally red state that President Biden won and where Democrats picked up two Senate seats, a law passed that gives the partisan state legislature more control over the administration of elections. The Republican nominee for governor in Pennsylvania has tried to overturn the state’s results in the 2020 election, has been subpoenaed to talk about his role in the Jan. 6 Capitol insurrection (though he denies doing anything illegal), and would have the power to appoint the secretary of state, if elected. As primary results continue to funnel in, those in other swing states, like Arizona, Georgia, and North Carolina, who falsely claim election fraud have also won Republican nominations for key positions including governor and secretary of state. For these reasons and more, outlets developing democracy beats are delving into the laws that govern elections and the people who administer them — areas that traditionally received little in-depth coverage when compared to the horserace.

Guarding democracy is much more akin to “watching a leak,” says Tony Marcano. “You have to pay attention, because that leak could turn into a crack that can turn into damage, and the next thing you know, your house is falling down”

It’s been clear for a while now that American democracy is in crisis. Barton Gellman, writing in December 2021 for The Atlantic under the headline, “Trump’s Next Coup Has Already Begun,” didn’t mince words: “The prospect of this democratic collapse is not remote. People with the motive to make it happen are manufacturing the means. Given the opportunity, they will act. They are acting already.” Indeed, Republican conspiracy theorists have been elected to Congress, and people who support the former president’s lie that the 2020 election was stolen are running for key positions overseeing elections. There are at least a dozen running for attorney general in states like Wisconsin, Michigan, and Arizona.

In putting together teams to address this threat, any outlet has to navigate a flock of concerns and questions: What should it cover — that is, what specifically constitutes a danger to democracy? What’s the best way to leverage possibly scarce resources and staff to address it? And which strategies help that information get to the people who need it most — including outside an outlet’s existing core audience?

Public opinion research shows there’s potentially a very large audience for reporting that illuminates the fragility of U.S. democracy. In short, Americans are worried.About a year after the attack on the Capitol, Americans were apparently “deeply pessimistic about the future of democracy,” per the result of an NPR/Ipsos poll that found 64 percent felt the system was “in crisis and at risk of failing.” Almost two thirds of those polled said they agreed U.S. democracy was more at risk than it had been a year earlier. Similarly, a national poll of young Americans released in December 2021 by the Harvard Kennedy School’s Institute of Politics found that a majority — 52 percent — of 18- to 29-year-olds considered the U.S. either “a democracy in trouble” or “a failed democracy.”

“I think a lot of Americans learned more about how their elections work because of what happened in 2020 than ever before. And we find readers are intensely interested in this process now,” says Matea Gold, national editor of The Washington Post.

The Post’s democracy desk setup includes the hiring of two editors along with three reporters stationed in Georgia, Arizona, and the upper Midwest. The Post named Griff Witte, a two-decade veteran of the paper, as democracy editor in late April; Matt Brown, formerly of USA Today, began work as the Georgia-based reporter at the end of March. Peter Wallsten, senior national investigations editor, is overseeing the team.

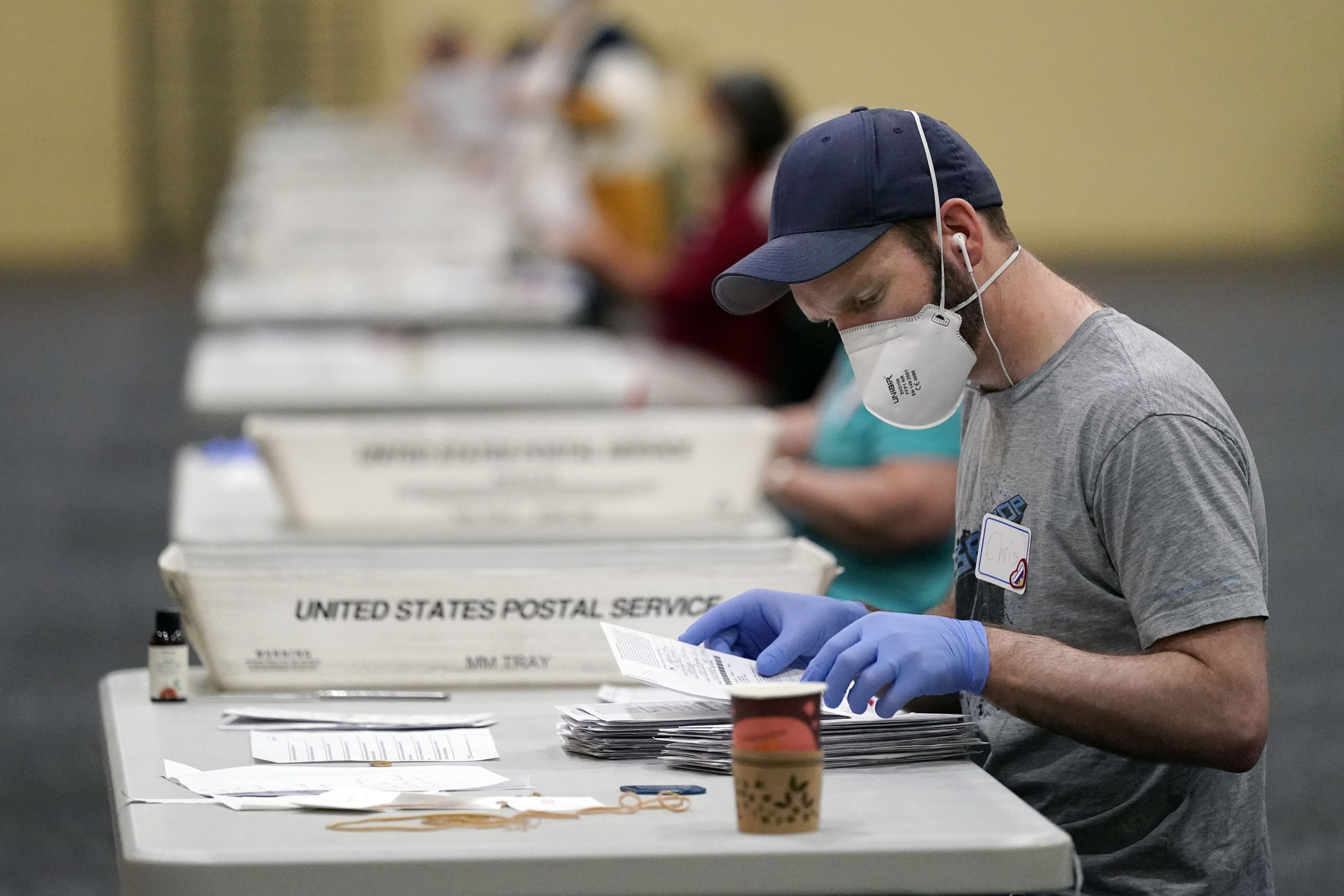

Workers prepare mail-in ballots for counting, Nov. 4, 2020, at the convention center in Lancaster, Pa. outlets developing democracy beats are delving into the laws that govern elections and the people who administer them — areas that traditionally received little in-depth coverage when compared to the horserace

Gold says the paper started development of the new desk before the Capitol insurrection.

“As I was mobilizing our coverage around voting in 2020, it became really clear that that would be an incredibly singular year for voting, just because of the pandemic,” she says. “We started putting together a pretty robust staffing plan to make sure that we had a very strong network of reporters who could cover developments in different states.”

Because The Post had those reporters in position, Gold says, they were prepared when “the story sort of changed midstream to being one about the pressures on a voting system in a pandemic to the pressures on an election system when a sitting president seeks to overturn the election results.”

In creating a formal democracy desk, The Post is focusing on “mastering and understanding what was happening on the ground when it came to both voting and elections, but also [the] more diffused impacts [on] how people view their government at this moment,” she says. “Do people still have trust in their public officials and the very process of electing our officials?”

For The Post, “this is a story that stretches into so many different beats, so it’s very important to us that we had a hub that really was helping bring together the strands of that reporting and making sense of it for readers,” Gold says.

That ranges from investigative reporting to local stories on voting or election laws to threats against public officials. It could include pieces about the process — and politicization — of how midterm elections will be certified or stories about the people affected by polarized politics and falsehoods, such as those profiled in The Post’s summer 2021 look at election officials enduring intimidation and threats just for doing their jobs. Much of their work will focus on holding public officials accountable for undermining elections. “We had never before seen [in] modern history such a sustained effort to really fuel doubt about how our elections work in such a systematic way — one that has cropped up in communities all around the country,” Gold says. “It’s really our obligation as journalists to create a really coherent plan to cover that, to be out front on that story, to be illuminating and to bring facts to bear.”

The paper’s democracy desk will not be solely Washington-based: The reporters working on the ground in Arizona, Georgia, and the upper Midwest will be specifically charged with covering “how local and state officials navigate pressures on the administration of elections, while tracking legislative and legal battles over voting rules and access to the polls” and “telling the stories of people and communities who have lost faith in the ability of their government to hold free and fair elections,” according to Gold and other top editors.

Newsrooms like the Washington Post are “mastering and understanding what was happening on the ground when it came to both voting and elections, but also [the] more diffused impacts [on] how people view their government at this moment,” says Matea Gold

The desk sits alongside The Post’s existing politics desk and its America team, which covers state-specific and regional issues. Democracy, and threats to it, Gold says, is “a story that goes way beyond politics. It’s actually a story about our relationship as citizens with our government.” A late April story looked at Georgia’s Republican gubernatorial primary through the lens of how “unproven claims that fraud tainted the 2020 election” might affect voters’ attitudes about the race. Another piece reported out of Michigan plumbed GOP leaders’ concerns that “the spread of election conspiracies is alienating swing voters and undermining public trust of elections.” Both pieces examine the lingering legacy of the former president, who has continued to push his discredited story of having lost a “rigged” election to Joe Biden.

To that end, The Post and other outlets are hiring or reconfiguring staff and recalibrating or expanding coverage, focusing on how to reach not only their current audiences with this reporting, but those outside that circle — including those who’ve cultivated a profound distrust of “mainstream” media, get their information from partisan outlets, or simply don’t have the time or inclination to focus on politics and politics-adjacent news. At The Post, Gold said, part of connecting with distrustful readers is explaining “how we do our work, why it’s credible, the lengths we go to verify information. … Educating people about what goes into our reporting is part of helping deepen the trust that they can feel in the ultimate stories that we produce.” (The Post’s website lays out its policies on attribution and the use of anonymous sources, for example.)

KPCC takes this seriously — so much so, managing editor Marcano says, that their new democracy reporter job is specifically set up to work hand-in-hand with an engagement producer. Part of the producer’s job is to help the station understand what information the audience wants and the best ways to deliver it to the people who need it. In May, for example, KPCC/LAist debuted an interactive “Meet Your Mayor” feature that helps the audience “match” itself with candidates that most align with their values. The feature is based on the candidates’ answers to audience-submitted questions, making the public the central focus of the feature before it was even published.

KPCC experimented with this back in 2015 with a unique series called Make Al Care, which centered on a Los Angeles County chef who had never voted in a local election to tell a bigger story about confronting voter apathy. The project, which asked readers to share reasons why Al should vote, was an effort to address one of the top challenges newsrooms face in covering civics and menaces to the democratic system: This stuff is existentially important, but in practice, it can be wonky and hard to cover in an engaging way.

Data visualization and interactives can also play a part, as with a Jan. 2022 New York Times feature that lets people gerrymander their own districts, essentially making a dry — but important to democracy — function into a sort of game. KPCC/LAist’s first major foray into the new democracy coverage is a “Voter Game Plan” project that includes a detailed FAQ on voting in L.A. County’s June primary, a way to ask questions about voting, several voter guides (some of which were produced by nonprofit partner newsroom CalMatters), and a customizable virtual ballot that voters can fill out, print, and take to the polls with them. After the polls closed on June 7, Rick Caruso is in the lead for L.A. mayor, though votes are still being counted.

Defining the beat and then figuring out how to present it most compellingly is part of what makes for effective coverage. At independent, nonprofit ProPublica, Editor-in-Chief Stephen Engelberg has given a lot of thought to how a democracy beat should work and what it should and should not be.

Engleberg cautions that “threats to democracy” doesn’t equate to “people whose opinions we don’t like [who] legitimately came into power.” As he puts it, if “there are people all over the place running for school boards and they’re getting out the vote and getting elected and their views are sort of more extreme than mine,” someone might say, “That’s a threat to democracy. Well, no — that is democracy.”

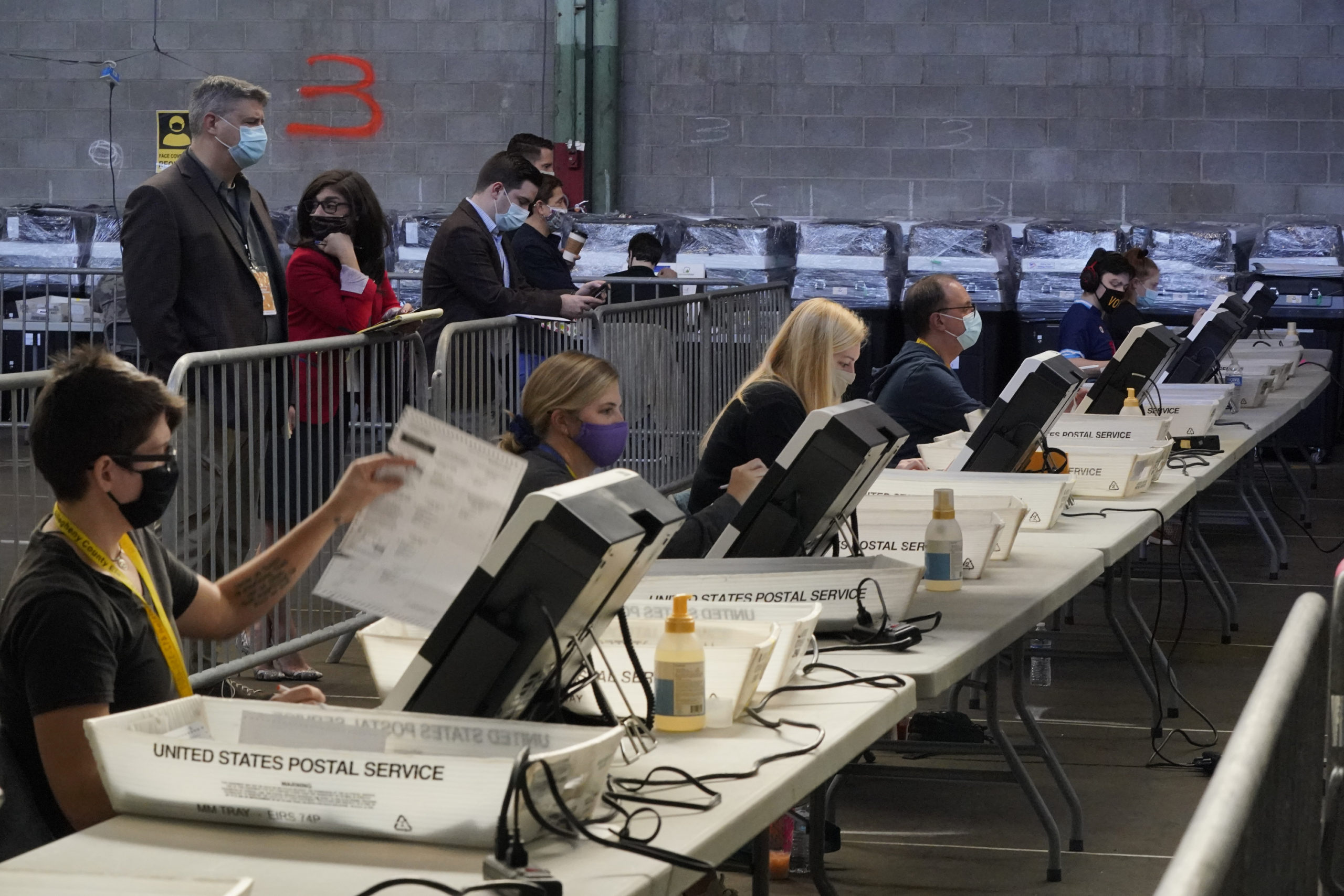

Maricopa County ballots cast in the 2020 general election are examined and recounted by contractors working for Florida-based company, Cyber Ninjas, May 6, 2021, at Veterans Memorial Coliseum in Phoenix

However, “there are an awful lot of efforts that you can see in various state legislatures to adjust the electorate to favor one side or another, or to adjust the voting boundaries to favor one side or another,” he says. “I think those are very, very much legitimate things to cover.”

In June 2021, ProPublica announced it hired Alexandra Berzon to cover “risks to democracy.” She subsequently moved to The New York Times in a similar role; ProPublica announced in April 2022 that it had hired Andy Kroll, formerly of Rolling Stone and Mother Jones, for that job.

In September, Berzon and other ProPublica reporters teamed up to investigate how election-denying followers of former Trump adviser Steve Bannon had mobilized to enlist as low-level GOP precinct officers, exerting a new level of control on the party from the very grassroots. Bannon, the piece explains, argued to his followers that Trump had been sold out by the Republican Party, and the answer was to rebuild the party from the ground up. “The result is a nationwide groundswell of party activists whose central goal is not merely to win elections but to reshape their machinery,” ProPublica reported. These new low-level officials have gone to work in their respective states to unseat Republicans leaders who pushed back against Trump’s election-rigging lies and questionable audits and have worked in support of state-level voting restrictions. The story underscores a critical facet of what a new era of democracy reporting needs to do: shine light on offices, elections, and government functions that some editors have too often dismissed in the past as second-tier stories — too granular, too time consuming, too low-stakes compared to coverage of races for president or even governor.

But research, including by the Brookings Institution, has shown that diminished coverage of House races by local media is related to decreased participation in the civic process and less government accountability.

Some of this may be changing as news outlets bring threats to democracy into sharper focus.

For example, while the 2022 midterm elections for Congress may be the big focus of some national (and local) media outlets, this year will also see contests for offices like secretary of state, which oversee the mechanics of elections. Audrey Trujillo in New Mexico, who has falsely claimed election fraud, recently secured the Republican nomination for secretary of state in New Mexico, while Brad Raffensperger, who refused Trump’s demands to overturn Biden’s 2020 victory in his state, won his primary for the same office in Georgia. Secretary of state races have “historically attracted little notice and even less money,” as The Guardian noted in March. But the secretary office is garnering more attention from voters, donors, and the press because of its key role in overseeing elections — especially in swing states.

When looking at evolving coverage of threats to democracy — including the language journalists use to describe the threats — it’s useful to draw a parallel to how the media currently covers climate change versus how it did so in the past, says Jane Hall, associate professor at American University’s School of Communication and author of “Politics and the Media: Intersections and New Directions.”Defining the beat and then figuring out how to present it most compellingly is part of what makes for effective coverage

“We know from political science [that if] you don’t connect the dots for people, they don’t really know how to hold public officials accountable,” Hall says. That was borne out over time in the “debate” over climate, both in what she calls the “hesitance” of news media to directly attribute environmental change to human behavior and the practice of “giving equal weight” to both those who believed in climate change and those who did not.

Over time — as news outlets revealed that climate change deniers received funding from the fossil fuel industry — the bothsidesism began to erode, Hall says. As the University of Colorado-based Media and Climate Change Observatory noted at the end of 2021, not only are U.S. media outlets covering climate change more, but the language these reports is more pointed: Phrases like “global warming” are on the wane, and terms such as “climate catastrophe” are on the upswing.

News outlets — notably in the Trump and post-Trump era — have been re-evaluating the use of the word “lie” in their reporting. There’s been a hesitancy to use it by outlets, reporters, and editors who say it at least implies the intent to deliberately mislead when the person in question may possibly just be confused or mistaken.

To a degree, a reporter might technically fulfill his or her mission by presenting the audience with a “this is what the person said” statement augmented by a “but this is the evidence to the contrary” clause. However — as the Trump era brightly highlighted — the press will often need to go further, drawing a distinction between a possible verbal gaffe, exaggeration, and a calculated, deliberate falsehood. Even before Donald Trump’s inauguration, Masha Gessen sounded an alarm in the The New York Review, saying he and Russia’s Vladimir Putin had track records of lying “to assert power over truth itself.” To media charged with covering leaders who demonstrate their clout by claiming the right to disavow facts at their convenience, Gessen said, “It is time to raise the stakes from fact to truth.” News outlets are getting more comfortable using the word “lie,” as that’s how many described what Rep. Kevin McCarthy did when he denied telling colleagues that Trump should resign after the insurrection even though New York Times reporters had him on tape.

READ MORE: The Midterms Are Coming. Here’s How to Cover Polling

“There’s still a reluctance to recognize just how severe the danger really is — and it’s not just among journalists,” says Monika Bauerlein, chief executive officer of Mother Jones magazine. “I think it’s also driven to some extent by the fact that a lot of political journalism takes its cues from the political establishment and elected officials, [and] there was also, I think, a reluctance among that group to really jump up and down about American democracy itself being at risk.”

Bauerlein — in a Dec. 2021 piece titled “What if Media Covered the War on Democracy Like an Actual War?” — argued that the media’s track record of covering perils to democracy incrementally and covering the politics surrounding it like a spectator sport instead of a snowballing national emergency, “represents a terrifying failure of our profession.” What if, she wrote, “we covered a wave of election rigging from coast to coast with the same fervor as a bump in inflation or a showdown in the Senate?”

In early April 2022, Reveal from The Center for Investigative Reporting rolled out a major investigation, “Inside the GOP’s Purge of Local Election Officials in Michigan,” which showed how Michigan has become a “test lab of the anti-democratic movement.” The piece details how Republicans were purging sitting election officials and replacing them with people who questioned the legitimacy of the 2020 outcome. It emphasized that what has long been seen as a “mundane bureaucratic process” — the work of county election canvassing boards — is now becoming a potential pivot point to further undermine trust in the entire voting process.

Election office workers process ballots as counting continues from the general election at the Allegheny County elections returns warehouse in Pittsburgh, Nov. 6, 2020. “It’s like all these like small little chess pieces happening in all these different hamlets around America, with the idea that perhaps this could all lead to the overthrow of the government in three years,” says Reveal's Andy Donohue

Andy Donohue, executive editor for projects at Reveal, says initially, the outlet took a broader-brush approach looking at multiple states but eventually settled on reporting about Michigan because “it was looking like a testing lab for the anti-democratic movement.”

“It’s like all these like small little chess pieces happening in all these different hamlets around America, with the idea that perhaps this could all lead to the overthrow of the government in three years,” adds Donohue, who predicted the rise of democracy beats in a 2020 piece for Nieman Lab. “It’s a harder thing to marshal all the resources around; it just requires more convincing and more education and learning and hiring and shifting resources.”

Even newsrooms that don’t have eye-popping budgets or an endless staff roster can find ways to address dangers to democracy and help more people understand and participate in civil society. The Berkshire Eagle of Pittsfield, Massachusetts, runs “capsule reports” on local town meetings that include a rundown of the votes taken and top issues discussed from proposed borrowing initiatives to charter amendments to changes in the composition of government. The Nevada Independent has offered readers a gubernatorial “Promise Tracker” that lets them compare campaign pledges on a variety of issues — including health care, guns, and the environment — to real-life outcomes in a visually clear and concise way.

For now, when it comes to fundamental questions of democracy and its survival, “I think it would be foolish in this moment [of] crisis to put a reporter on and then in a relatively short time walk away and say, ‘Okay, that’s over,’ because I think that history belies that,” ProPublica’s Engelberg says.

“Call me up in three years and see what happens. But if there’s a bigger problem than this,” he reflects, “I hate to think of what it would be.”