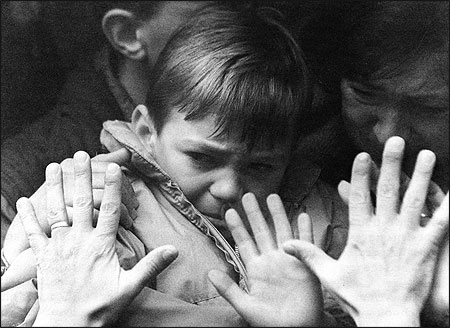

A father’s hands press against the window of a bus carrying his tearful son and wife to safety from the besieged city of Sarajevo during the Bosnian War in November 1992. Photo by Laurent Rebours/Courtesy of The Associated Press.

The novelist Adam Thorpe, writing in The Guardian (U.K.) newspaper, recently reviewed my book, “The Place at the End of the World: Stories From the Frontline.” It was a very good review but, as always, when one reads something written about oneself, there are interesting revelations, to say the least.

“War is di Giovanni’s staple subject,” he writes. “She’s covered it in places such as Rwanda, Iraq, Bosnia, Sierra Leone, Chechnya and Afghanistan. She’s not quite sure how she’s survived, and neither are we.” That part made me laugh. I’m afraid it is true.

Later Thorpe writes that in my 18-year career, I have gone to “suicidal lengths” to bear witness to human rights abuse around the world and to bring back the stories of the “small voices.” He describes me as “stubbornly brave.” I like reading these words, but they embarrass me, too. Stubborn I am, fiercely and annoyingly so. But brave is not something I would call myself.

As a child I was afraid of the dark. I still hold an irrational horror for jungle creatures: spiders, insects, large things with wings. I sometimes sleep with the bathroom light on if I am alone and get up at least five times to make sure all the doors are locked and the windows barred. And once, in a guesthouse in Liberia during the civil war, I was so frightened of what lay outside my door that I barricaded the room with chairs and drugged myself to sleep with a codeine painkiller that a United Nations doctor had slipped me in case of gunshot wounds.

Some of the places that I have been have been very frightening. There are things I will never forget. The early, frozen dawn of a Grozny suburb after Russian forces had taken the city, when I huddled in a potato cellar with an old woman listening to the bombardment and sure I would be dead by daylight. Watching an Ivorian soldier slowly raise his gun to my chest after I screamed at him to let me take a wounded man to the hospital in my taxi during the first day of the coup d’etat. The sound of rapid gunfire over a bush in Sierra Leone, where a few seconds before there had been stillness. Then the rush of chaos. My car being surrounded by teenage, drugged soldiers in Freetown who waved RPG’s and demanded that I get out so they could rape me. The terrible hollow sound of a bomb being dropped near my base camp in Kosovo and the screams of pain from the people that it hit.

I have been terribly frightened at times, but innermost in my mind was that I would always survive. Why, I am not sure, but I believe it probably has something to do with faith. A friend of mine, a former combat photographer once said, “I never think I will get hurt because my mother loves me too much.” It sounds ridiculous, but everyone has their own reason as to why the bullet that hits the guy next to you won’t hit you.

I believe the work that I have done over the years is important, and I am proud when I get a letter from an ordinary person, someone in Middle America or Middle England, a housewife or a teacher or a radio technician, who writes and says, “Thank you for your compassion.”

But I don’t think of myself as courageous. Because courage is meant for the people I leave behind — the civilians who could not cross the frontlines of Sarajevo to leave the debilitating medieval siege. The young boy in Mogadishu who helped me find my way through the maze of clan warfare and who told me how one day, walking down the street with his brother, he heard the whiz of a bullet, then found his brother dead on the ground next to him. Or even that old woman in the potato cellar in Grozny, who got up from the cellar at one point to make us tea on a camp stove.

I went to lots of terrible places. I got marched in the woods by Serb paramilitaries with a gun pointed at my back. I got stuck in dangerous places in Africa. I slept a terrible sleep on a door frame in East Timor and waited for an assault from rebels with machetes. But eventually — and sometimes it took weeks and even months — I got out, I went home, I took a hot shower, I ate a good meal. I went to the cinema, I slept in a real bed with clean sheets. The people who befriended me, who shared their rice, who made me laugh, who helped me find water to wash, did not. They stayed behind.

That is always the guilt of the reporter who covers conflict. You survive, someone else does not. And why? And why is it that I was born in a comfortable suburban American hospital and had good shoes and music lessons, and someone else was born in Srebrenica and was of fighting age in 1995, so therefore is probably dead? These are the things I think about when I go to sleep at night, and because of that I do know that I have something that is known as compassion.

But courage is reserved for other people.

Courage was my father bravely and doggedly fighting cancer, saying right up until the very end, “I’m not going to let cancer kill me!” And trying to be brave so that we would not falter.

Courage is Lotti Latrous, a wealthy Swiss woman who gave up her entire life, including her family, to sleep on the floor of a hut and nurse Ivorians dying of AIDS who had been left to die in the street.

Courage is Felicia Langer, an Israeli Jewish woman who inspired me to do the work I do now, who for many years was one of the few Jewish lawyers defending Palestinians in military court. The cost she paid to defend the enemy was being constantly worried about her own personal security.

Courage is the Kosovar Serbs who hid Kosovar Albanians in their homes during the NATO bombing in 1999.

Courage is the mothers of Srebrenica who saw their menfolk walk into the forest in July 1995 to defend their town against a brutal onslaught — and never return.

Was it Hemingway who described courage as grace under pressure? I am not sure. But when I think of that, courage is not me, a clunky reporter clutching a notebook and treading on people’s lives, trying to get them to open up their souls.

Grace under pressure is Gordana Knezevic, a Bosnian of Serb origin who managed not only to bring out a newspaper every day of the siege — the embattled and wonderful Sarajevo daily Oslobodjenje — but to raise her children in the back room of her house because it was farther from the street and thus safer from errant shrapnel or snipers’ bullets.

Courage is my old interpreter Mona in Baghdad, who stuck by my side through the darkest days of the Saddam times and during and after the invasion.

Courage is the man who drove through Russian tanks to bring me out of Grozny after he heard my newspaper reports aired on Russian television, and he knew that if Russian soldiers found me, they would probably kill me.

Courage is all of these people and a million more who are embedded forever in my notebooks. Ordinary people. The bravest souls are the ones who keep families together during war, who manage to continue their lives without going mad.

RELATED WEB LINK

Janine di Giovanni’s Web site

– Janine di GiovanniNo, a reporter’s role is to bear witness. And if we have the ability to do so — the financial backing of a paper or a TV company, the guts and the vision — then we have an obligation more than anything. Martha Gellhorn once wrote about loving only one war, and the rest being duty. I still feel like that — Bosnia was the war that took and broke my heart in a million little pieces. But Africa, the Middle East, Asia, the rest of the world, the places I will go and bring back a story that I hope someone will read, and then go to bed that night thinking: “Thank God I don’t live in Mogadishu” and gain some kind of insight, some kind of compassion — that to me is my responsibility.

Janine di Giovanni is the author of “Madness Visible: A Memoir of War,” published by Knopf and “The Place at the End of the World: Stories From the Frontline,” published by Bloomsbury in the United Kingdom. She has reported on numerous wars and conflicts and has won two Amnesty International awards, the National Magazine Award, and been named Britain’s Foreign Correspondent of the Year.