All photos by Peter van Agtmael.For the past two and a half years, I have covered war and its consequences in Iraq, Afghanistan and across the United States. As an American and a member of the generation fighting the wars, I wanted to create a record of the individual lives caught in history’s unpredictable path. I hoped my experiences would help me to figure out what it means to be human, but I found few easy answers. The only truth I discovered is that fear corrupts everything. In the pictures I took I tried to reflect the complex and often contradictory experiences I encountered in which lines were continually blurred between perpetrator and victim, hero and villain.

It is said that war is man’s nature, and the lessons of history are fleeting. Yet by bearing relentless witness, journalists have helped end conflicts and changed the way wars are waged. Good pictures tell us something recognizable and deeply felt about our existence and ourselves, and so through the sharing of such images lies the antidote to war. I don’t expect to see profound change come in my lifetime; as Chinese Premier Zhou Enlai observed, when asked in the 1970’s about the effects of the French Revolution, it was still "too soon to tell." I do believe that ultimately the collective weight of testimony will help to end armed conflict, and I want to do my part.

A freshly dug grave is covered by a late winter snow in Section 60 of Arlington National Cemetery. Section 60 is reserved for the dead from Iraq and Afghanistan, and more than 400 fallen soldiers from those conflicts are buried there. It usually takes a few weeks after burial for the carved marble gravestone to be completed and placed at the grave. Until then, a small waterproof plastic marker containing the name and rank of the deceased is plunged into the dirt.

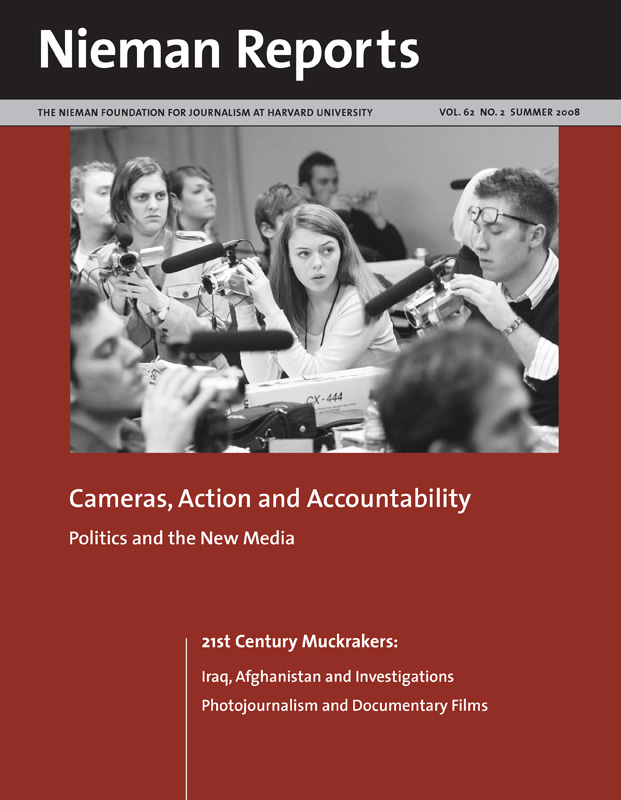

Fragile Alliances and Tragedy

Lt. Erik Malmstrom and Lt. Matthew Ferrara (left and right in photo above) meet with the village elders of the town of Aranas, an ancient and isolated town in eastern Afghanistan’s Waigul Valley, a major point for extremists transiting to join the jihad from Pakistan. Malmstrom was on the final days of a 16-month deployment, and Ferrara had arrived the previous day to replace him. A year earlier, Malmstrom had set up a small outpost above the village with a platoon of 30 soldiers. Initial reactions to his presence were hostile. Several months after the outpost was built, Malmstrom’s unit was ambushed. Three of his men were killed and another three were wounded, 20 percent of his total strength. Many combat units lose their fighting effectiveness after the loss of so many men, but Malmstrom was determined to change the valley. Over the next nine months, he formed an alliance with the village elders, built a school, brought electricity to the town for the first time via a small hydroelectric dam, and began constructing a road connection to the nearest regional hub. Although there were a few scattered firefights, Malmstrom managed to win the loyalty of the town elders and served out the rest of his deployment in relative peace.

But alliances are tenuous and often of convenience. Shortly after Malmstrom’s unit left Aranas, foreign fighters decided to take advantage of the inexperienced new unit and launched a major attack on the base, disguised as local Afghan security forces. The base was nearly overrun, and Ferrara was forced to call in an air strike on his own position. In the end, the attackers were driven off, but not before 11 of Ferrara’s men were wounded and two Afghan soldiers killed.

After the attack was repulsed, nominal stability briefly returned to the valley.

On November 9, 2007, Ferrara and his men were returning from a meeting with the village elders when they were attacked at close range by a large number of Taliban fighters. Ferrara was killed instantly, along with five other Americans. Three Afghan soldiers were also killed, and 11 Americans and seven Afghans were wounded. Only two men on the patrol escaped being wounded or killed. It was the deadliest incident against U.S. forces in Afghanistan in 2007. Following the ambush, the outpost was abandoned, and the valley returned to insurgent control. All the hard-fought gains of the previous year and a half were lost.

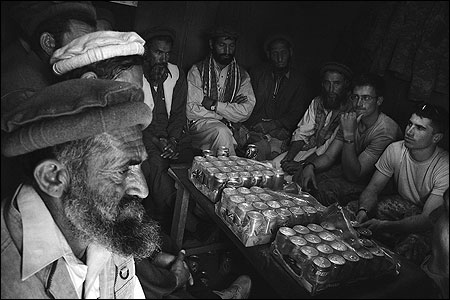

Ten days later, Ferrara’s funeral was held in Torrance, California. It was attended by hundreds of local community members, as well as many of his friends from the U.S. Military Academy, where he had graduated from two years before his death. He had been one of the top students in his class and was greatly admired by his classmates for his unruffled leadership qualities and generosity of spirit. His family was in shock, unable to process the events that had ripped their lives apart in an instant. His sister Simone remarked that it felt like she was attending someone else’s funeral. Matt’s parents, Mario and Linda, wore their faces in a mask, saving their tears for private moments with the family. Ferrara’s three brothers openly wept. The eldest, Marcus, a major in the U.S. Army, had previously served in Iraq. After the funeral service he spent a long moment looking at his brother’s body, waxy and stiff from the extensive reconstructive portmortem work. When he raised his gaze from his brother’s body for the last time, his face crumpled into a choking sob. Matt’s two younger brothers, Andy and Damien, are both cadets and hoped to become infantry officers just like their older brothers.

Remembering Three Who Perished

Lieutenant Erik Malmstrom of the 10th Mountain Division turns away grimly from photographs of three of his soldiers killed in a Taliban ambush in eastern Nuristan Province on August 11, 2006. The ambush wounded three other Americans. Portraits of 40 other soldiers killed during the deployment fill the remembrance room at the brigade headquarters in Jalalabad, the city where Osama bin Laden was last sighted. Erik had arrived on base just minutes before, the first of many stops required (Kabul, Kyrgyzstan, Ireland) to return home after a 16-month deployment leading a platoon in the remote Waigul Valley in eastern Afghanistan. His brigade of the 10th Mountain lost the most men of any single unit in Afghanistan since the war began, more than 10 percent of the total U.S. fatalities in Afghanistan since 2001. The portraits of the fallen were hung between an iconic image of 9/11 and a photograph of flag-draped coffins of U.S. soldiers. The juxtaposition was meant to offer visitors a pointed reminder of the reasons and risks of their service.

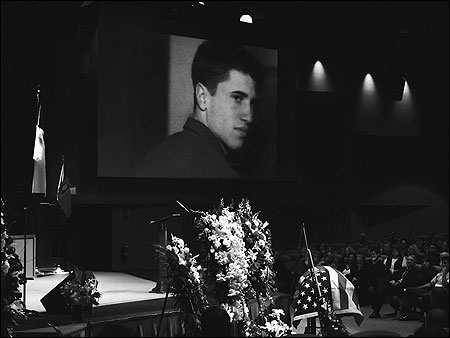

Weary Rest in the Midst of a Raid

Sergeant Jackson rests wearily as his squad searches a home during a raid in Rawah, a restive Sunni town near the Syrian border. Most raids occur at residential homes, where the suspected insurgents live with their families. Because the raids are usually carried out late at night, the suspect is often sleeping with his family, usually on padded mats in a communal room. The raids are abrupt, and generally the men are restrained before they can react. However, the intelligence is often faulty. The intended targets of the raid were apprehended in perhaps 15 percent of the dozens of raids I witnessed, leaving most victims terrified and angry. Sometimes the commanding officer would compensate for the damage and misery on the spot, extracting a wad of soiled dinars or dollars and pressing them into hesitant hands. Other times they would simply leave in search of the proper target or return to base before insurgents had the chance to organize and attack them.

A Medic’s Struggle with the Pain of War

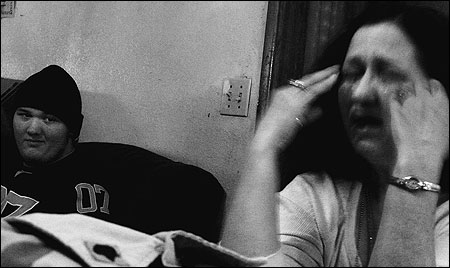

Donna Thornton weeps as she remembers her son James Worster, as younger son Josh looks on helplessly. James died September 18, 2006 of an overdose of propofol. "Jimmy," to his friends, was just weeks away from leaving Baghdad at the conclusion of his second tour of duty. He had joined the Army in a patriotic fervor following the September 11th attacks. He was trained as a combat medic, and in 2003 he was deployed to Iraq. His unit was sent to a dangerous part of Tikrit, Saddam Hussein’s hometown, where his skills were quickly and frequently tested. He came back to the United States in the middle of 2004, deeply troubled by his experiences, and sought counseling for posttraumatic stress disorder. He was put on a regimen of antidepressants, and his Army-appointed psychologist recommended against redeployment. His spirits began to improve as the medication took effect, and he returned to relative normality with his wife and young son, Trevor.

In 2005, he was transferred from his infantry unit to the understaffed 10th Combat Support Hospital (CSH), which was poised to deploy to Iraq to run a military hospital in the Green Zone in Baghdad. Although his psychologist had recommend to the Army that he not be allowed to redeploy, the staffing officers believed that taking him out of a direct combat setting would suffice, since the unit needed all the experienced medics it could get. Being a patriotic and loyal soldier, he did not object and deployed back to Iraq in September 2005.

The 10th CSH quickly proved to be a nightmarish place. One of the first batches of casualties was a group of Marines that had been hit by a suicide bomber as they were on a foot patrol. Seven men came in, with seven legs and seven arms between them. Five of them died in agony on the operating table. Things only got worse. The doctors, nurses and medics of the 10th CSH treated dozens of casualties every day as they supervised the emergency room of the busiest military hospital in Iraq. Although the staff saved the lives of more than 90 percent of the soldiers who came through their doors, the failures began to take their toll on the staff, especially the young medics. In the heat of the action, they began hoarding leftover painkillers, and in their off hours would take them in order to sleep. Soon, nearly a third of the medics in the hospital were self-medicating with stolen drugs.

In April 2006, James went home on leave. His wife had grown distant in his absence, and he feared the worst. One day, as he was joy riding in his new Mustang, his son Trevor pointed to a house and said, "That’s where Ken lives." Jimmy didn’t know anyone named Ken, and when he confronted his wife, Brandy, she admitted that she’d been having an affair. As he dug deeper, James found out that Ken had been only the most recent in a long series of affairs. At the end of his 14-day leave he returned to Iraq, completely devastated.

His friends remember he was a changed man when he returned to Iraq. He was quieter and no longer joked around with the other staff. He began taking more painkillers and, along with another medic, began injecting himself with even stronger medications. He followed news of his wife’s affairs via her MySpace page, where she published detailed, gloating accounts. His drug use kept escalating, and he became increasingly private. A medic with whom he began his own affair reported the drug use to the senior staff of the hospital, but they ignored the warnings.

Early in the morning on September 18th, the unit gathered for formation before reporting to work. Jimmy was missing. One of his friends went to his room to check on him and found it unlocked. Jimmy was slumped against the floor, a needle still stuck in his arm. His friend tried to resuscitate him, but Jimmy was cold, his lips were blue. The unit redeployed to the United States a few weeks later. The top officers were relieved for failing to act on the warnings of the whistleblower. Jimmy’s drug buddy was thrown in jail, where he awaits a court-martial. Many of the other medics struggle with what they’ve witnessed and, despite Jimmy’s death, in some cases their own drug use has escalated. The unit was reassigned and scattered across the country, but their struggles persist.

One and a half years later, Jimmy’s mother awaits a promised final report from the Army assigning blame and explaining failures in the chain of command that helped lead to his death.

Facing Recovery with an Unflinching Spirit

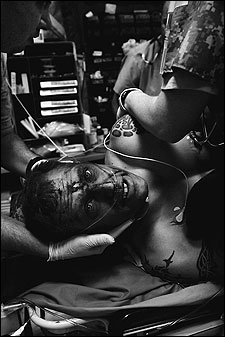

Jeff Reffner, 23, is treated by medics and doctors of the 10th Combat Support Hospital minutes after he was wounded by an IED that impacted on his Humvee outside Baghdad. Reffner, from Altoona, Pennsylvania, was on his second tour to Iraq. He had his left leg shattered and received burns to the hands and face after his Humvee caught fire when he was still unconscious from the force of the blast. He came into the emergency room in incredible pain but tried not to be a burden as he periodically flashed toothy grins at the concerned staff hovering above him and complimenting them on their taste in music, a smooth-voiced Jack Johnson strumming his acoustic guitar lightly and cooing pleasantries about surfing the California shore.

Reffner’s biggest concern after he was wounded was the condition of his buddy Jeff Forshee, a smooth-faced 20-year-old who lay quiet and unflinching as doctors gingerly touched his right ear, ripped in half by the explosion. Reffner was sent to the United States to recover from his wounds, while Forshee was sent back to their unit after having his ear stitched back together and was back on patrol in Baghdad a few weeks later. He survived the deployment, but Forshee suffers from severe posttraumatic stress disorder as a result of his experience. As of April 2008, nearly two years after being injured, Reffner is still in the hospital, recovering from his wounds. He recently had his 28th surgery.

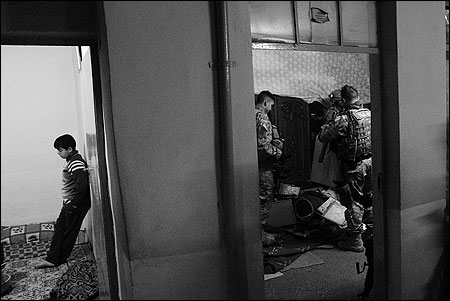

A Boy Awaits Questioning as Soldiers Ransack His Home

A teenage boy separated for questioning leans against a wall, while in the next room American soldiers ransack cabinets looking for contraband. The house had been raided on a hunch, as a passing American patrol noticed two young men fidgeting and eyeing them suspiciously. Anticipating violence, the patrol immediately detained the men and stormed into the house to look for evidence of wrongdoing. Everything was thrown onto the floor — toys, dishes, exam papers, blankets, a radio, and tricycle. In the next room the boy was questioned. "Had he seen anyone unusual around the house lately?" "Were his brothers coming and going at strange hours?" He muttered noncommittal answers, never making eye contact with the towering soldier who questioned him. Although nothing was found in the house to suggest insurgent activity, the hands of the two brothers came up with a faint residue of explosives when tested. The pudgy, gentle lieutenant in charge of the platoon decided to detain the men, although he suspected they were completely innocent and would probably be released in a few days. Still, they were blindfolded and their hands secured with plastic cuffs. At this, the previously docile mother, father and two wives began wailing, throwing their arms into the air, shaking and dipping wildly, begging for leniency. Their desperation was familiar to the American soldiers and, glassy-eyed, they pushed the two stumbling men towards their armored vehicle.

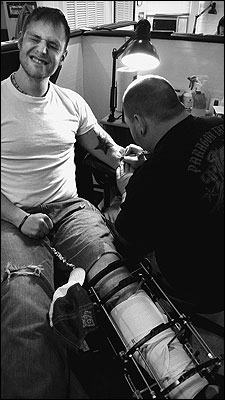

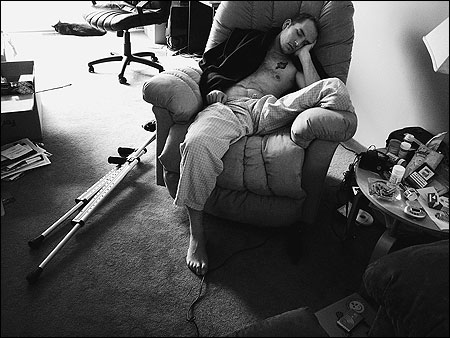

Coping With Life After a Disabling Rocket Attack

Raymond Hubbard was injured in Baghdad on July 4, 2006, when a Russian made 122mm rocket crashed 20 feet away from the guard post where he was stationed. Dozens of pieces of shrapnel tore into his body. One ripped into him just below his left knee, immediately amputating his leg. Another cartwheeled through his neck, severing his carotid artery. As he hit the ground he was still conscious and stared in numb disbelief as the horrified faces of his comrades gathered above him, speaking consoling words, and forcing him down when he tried to see the damage done to his lower body. A medic arrived on the scene moments after the blast. Raymond was already hemorrhaging massive quantities of blood from his severed artery. The medic, thinking quickly, plunged his hands into Ray’s neck and clamped the artery hard, stemming the blood flow. Still, the damage had been done. Raymond had already lost 14 pints of blood and suffered a massive stroke. He survived surgery and was sent to Germany. For over a month he lay in a coma.

When he woke up and slowly began to realize what had happened to him, he was deeply troubled. Nearly 40 years before, his father had been in a guard tower in Vietnam when it too was hit by a rocket. He was severely wounded, and Raymond’s injuries bore an eerie similarity to his father’s. Raymond and his father had never been close. His father had never recovered emotionally or physically from his wounds, and Raymond’s early, pained memories are of a house in squalor and his father drinking heavily. When Raymond was 15, his father died from complications related to his alcoholism. Shortly afterwards, Raymond dropped out of high school, and the years that followed were a blur of drugs, alcohol and failed relationships. He had two sons by the time he was 18 but, when he met Sarah, everything changed. He cleaned up, got a job, bought a house, and joined the National Guard. A few months after their marriage, he deployed to Iraq. Eight months later, he was blown up.

As Raymond slowly began to recognize the enormity of his injuries and the profound impact it would have on his life, he feared that his loss would impose the devastating cycle of war and its aftermath on his own sons, Brady and Riley. He felt as if his family was cursed. Although committed to avoiding his father’s crippling mistakes, Raymond often descends into darkness and depression as he contemplates his loss. The rocket attack took his leg, but the stroke and the coma also took part of his mind. He has trouble concentrating and organizing his life. The pain of his injuries often keeps him up at night.

Raymond would like to move on with his life. He wants to go to college, get a job, and some day run for elected office on a platform of reforming the Veteran’s Administration. But he is still tied to the excruciatingly long process of getting out of the Army. In order to be discharged with compensation for his injuries, he needs to go through the Army "med board," which assesses the physical and mental injuries to damaged soldiers and, according to a nebulous formula, assigns a percentage of their salary when they were injured to be paid out monthly over their lifetime. Raymond has been told to expect that the loss of one of his four limbs will likely lead to a disability compensation of 25 percent of his total salary per year for his lifetime. He fears that his physical and mental injuries will prevent him from finding a job that pays enough to make up the other 75 percent of his salary. Although he still loves the Army, and is proud to have served his country, he feels betrayed that the military will not provide for him fully after all he has sacrificed.

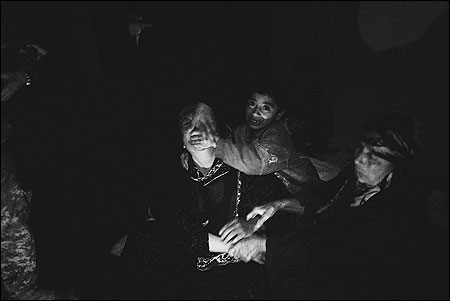

A Grandmother’s Fury

A grandmother, furious at U.S. and Iraqi troops detaining a member of her family, leapt up and tried to claw at them as they marched the detainee towards an awaiting vehicle. As she leapt, she was restrained by her terrified young grandson, who covered her mouth as she shouted raspy, shrieking curses at the indifferent soldiers. Two other women helped force her back down, where she sat rocking and muttering as the soldiers filed out.

A Helicopter Rescue Turns Violent

An Afghan soldier with a grave head wound from a roadside bomb regains consciousness in a U.S. medevac helicopter. The soldier, dazed and demented from the severity of the injury and the unfamiliarity of the thundering chopper, pitched his head back and began wailing in ever-increasing shrieks of pain and fear. When Flight Medic Michael Julio tried to ease his pain with more medication, the soldier began punching, kicking and biting Julio and Sergeant Sean Crowley, another medic sent to assist him with the casualties. Despite his head injury, the Afghan possessed Herculean strength and managed to keep the medics away through his wild flailing. His violent spasms began to upset the safety of the choppers flight and, finally, by enlisting the help of the crew chief and myself, he was restrained. Although Julio pushed more pain medication into the gravely injured man, he continued bucking and writhing. Upon arrival at Bagram, seven medical staff were needed to restrain him as he was taken from the helicopter and brought into the emergency room. Still, he managed to squirm free, biting deeply into Julio’s arm as he assisted the doctors and nurses. Julio did not expect the man to survive. After dropping patients off, medics do not follow up on their progress, reluctant to make any emotional attachments that might compromise their ability to do their job over the long term. After cleaning up the bite wound, the crew of the helicopter went off to buy extra large coffee smoothies at the Green Beans coffee franchise situated on the base.

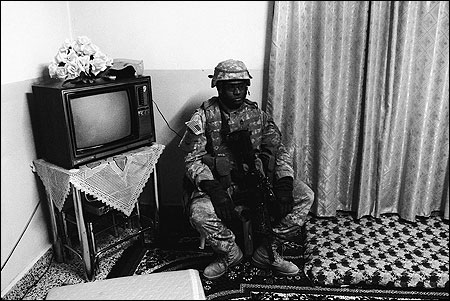

The Last Tour of Duty

A memorial service was held for Kevin Jessen, killed the previous day at the age of 28 by an improvised explosive device. He died in the restive former Baathist stronghold of Rawah, in Anbar Province. He left behind a wife, Carrie, and a two-year-old son, Cameron. It was his third tour to Iraq. He was a recent arrival to the unit and not well known to most of the other soldiers. At the memorial service, bagpipes played a mournful hymn, while the 400 soldiers that manned the base each filed past and saluted the memorial.

In a tent reserved for passengers in transit, a lone civilian sat and wept after the funeral. He was an Internet service technician working in Iraq as a contractor for a Halliburton subsidiary, lured by the high pay and the opportunity to "do his part." He had arrived the previous day by helicopter, and Kevin had picked him up at the landing pad. They had a friendly talk and decided to continue the chat over dinner at the chow hall that night. The next day, Kevin went out on a patrol and was killed. The technician’s job usually insulated him from the daily realities of the war. Kevin was the first soldier he’d known who died. He pledged that at the end of his contract he would leave Iraq and never come back.