Lobbyists crowd around the main entrance to the house chamber’s doors in Indiana’s statehouse. Photos on this page courtesy of the Indianapolis Star/Frank Espich.

While Washington, D.C. slows down during a presidential election year, state lawmakers continue to pass laws dictating everything from the quality of the public’s drinking water to the price they pay for utilities to their access to health benefits. During 1999, nearly 38,000 new laws passed in the states, an increase of 42 percent from the year before. In the first two months of 2000 alone, more than 60,000 bills were introduced.

With state legislatures now tackling issues previously dealt with only on Capitol Hill, their clout is at an all-time high. As a result, more national interests clamor for the ear of state policymakers. And the influence game gets played the same outside the beltway as it does inside, through an influx of campaign cash, sophisticated lobbying, junkets, gifts and business relationships. Throw in weak, unenforced ethics laws at the state level, and “business as usual” in statehouses across the country would often be tagged as illegal in the halls of Congress.

As state budgets remain flush with money and state legislators’ power increases, journalists must shine a brighter spotlight on what goes on behind the scenes through an ethics-oriented approach to reporting on state legislatures. In its role as watchdog, the statehouse press needs to watch more carefully for signs of undue influence by bankrolled groups seeking legislative favors—at the public’s expense—and examine how the lawmakers’ private concerns influence the laws of the states in which they serve.

During the past few years, several newspapers have followed carefully contributors’ money, devoting series of articles to uncovering who is pouring cash into state races and what state lawmakers have done to help their backers.

- Through a four-part “Statehouse Sellout” series from 1996 to 1998, The Indianapolis Star and News described to readers how special interest money flows into the state legislature and how lawmakers are pressured to vote in favor of those interests. By following the money, the reporters discovered that about 20 percent of campaign funds state lawmakers spent had little or nothing to do with getting elected: Most of the money landed in other candidates’ campaign accounts, in addition to funds being sent to athletic ticket vendors, car dealerships, and babysitters. They identified lawmakers who sponsored legislation after receiving donations from donors with interests in the legislation.

- In 1998, the San Francisco Examiner’s series, “The Money Machine: Big Spenders in California,” detailed how the state’s top contributors had given more than $76 million to legislative races since 1990 and, in doing so, had been able to kill proposed legislation they opposed during that time.

- In 1999, the Sun-Sentinel (Fort Lauderdale, Fla.) and The Orlando Sentinel joined forces for “The Price of Influence,” a five-part series exploring how gambling, health care, sugar, telecommunications and tort-reform interests sought favors from legislators in power after flooding money into their statehouse campaigns.

With more states making contribution data available electronically, state-based campaign finance reporting, once found primarily in multi-part series, can be incorporated into daily deadline stories. Journalists can now access Web sites that sort and collect valuable state contribution data. For example, Investigative Reporters and Editors’ Campaign Finance Information Center collects such data and makes it available to reporters for download, while the National Library on Money in State Politics allows reporters to track contributions to state lawmakers in 28 states. And in states in which campaign data has not been made available electronically—New York and Virginia, for instance—competing news organizations pooled resources to computerize this data on their own. With faster access to data about financiers of local candidates, more reporters across the country can follow the money flowing into state campaign coffers.

Yet tracking campaign contributions is not the only way to tell readers how outside interests attempt to influence the legislative process in the states. Take state lobbying, for instance. In its recent study of state legislatures, the Center for Public Integrity found that for every state lawmaker in this country, there are at least five registered state lobbyists. But the dollar amount these state lobbyists spend attempting to influence legislators is unknown because several states fail to tally what lobbyists spend.

The good news is that insightful investigative reporting can, from time to time, make up for the lack of public information on state lobbying.

- In 1998, The Palm Beach Post ran a three-day series examining exactly how lobbyists befriend lawmakers in the Florida General Assembly. To do this series, the paper examined thousands of lobbying reports, collected more than 200 records requests from public entities, and sent a questionnaire to the state’s 160 legislators.

- In 1999, The (Baltimore) Sun detailed the story of one Maryland lobbying firm that spent $400,000 to cozy up to state officials over a three-year period. Sun readers learned exactly how the firm connected with state officials—by handing out $87,000 worth of event tickets to state officials, contributing thousands to state officials’ pet charities, and hiring people with connections to those in power in Annapolis.

Despite the gains in access to contribution data, loopholes in ethics and disclosure laws keep journalists from learning about what goes on behind closed statehouse doors. In nearly every state, special interests can pay for legislators’ trips, yet in 17 of these states, lawmakers do not have to divulge who paid for their travel. The Center recently found that, in nearly half the states, lawmakers can hide significant categories of information about their private financial interests from the public and the press because of gaps in existing laws.

With 41 part-time state legislatures in this country, it is equally important for journalists to report the flip side of the “outside interest” story. To do this requires reporters to examine lawmakers’ private financial interests and professional activities to assess how those interests might affect state policy. The conflict of interest story is not new to local media, as evidenced by recent stories uncovering state lawmakers abusing their positions of public trust for private gain.

- This past March, The Philadelphia Inquirer examined the ties between the financial interests of Pennsylvania lawmakers and their legislation in a five-day series of investigative articles. They found that 68 of the state’s 253 legislators have co-sponsored legislation that could help their own, their employer’s, or a close relative’s business interests.

The Center for Public Integrity recently completed a two-year investigation of how state lawmakers’ jobs, investments and business interests intersect with public duties in all 50 states. In essence, we created a snapshot of state lawmakers’ outside interests, and we laid out how these interests commonly become part of lawmakers’ legislative agendas. We found thousands of state lawmakers routinely sponsoring and voting on legislation that could boost their private sector incomes. Some lawmakers set up consulting companies to charge fees to clients who need to understand complex legislation they wrote. Others own businesses solely supported by the patronage of lobbyists seeking legislative favors. Others write laws that would help their law firm clients. Still others head up nonprofit organizations that derive funds from businesses with interests before the committees they chair. And others sponsor legislation benefiting their employer. But because conflict of interest laws are ridden with loopholes, lawmakers are almost always acting within the letter, if not the spirit, of these laws. The current state of lawmaking at statehouses across the nation can mean putting personal interests first—even at the taxpayer’s expense.

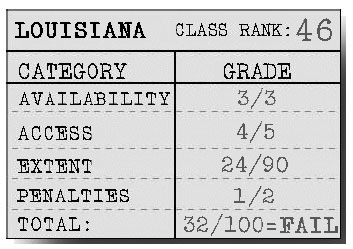

The Center for Public Integrity’s “50 States” project analyzes personal financial disclosure laws in state legislatures. They consider four components of the process, issuing a possible total of 100 points. Then they issue report cards on each state’s performance.

All of this is happening at a time when surveys find that fewer reporters are working the statehouse beat. Yet these are precisely the kinds of stories that the public needs to have reported. Without such a spotlight thrown on practices that might be compromising the legislative process, the influence of private interests—including those of legislators themselves—will only become more institutionalized behind closed doors. This shouldn’t be happening at a time when technology can assist reporters in retrieving the data that can help them to tell these important stories. By taking a comprehensive, ethics-oriented approach to reporting the statehouse story, this beat can be reinvented, revitalized and once again read widely by a public that needs to be informed.

Diane Renzulli is Director of State Projects at the Center for Public Integrity. In 1996 and 1997, she worked with local media through the Center’s Power and Money in Indiana and Illinois projects.