In 1977, The Daily Californian, the University of California-Berkeley’s student paper, filed a Freedom of Information Act request for documents bearing on FBI surveillance in Berkeley during the ’60s and early ’70s.

Four years later, Seth Rosenfeld, then a Daily Cal reporter, reviewed the 9,000 pages the FBI had finally released and wrote a few stories. Struck by how many files were missing or blacked out (“I wondered whether the bureau was America’s biggest consumer of Magic Markers,” Rosenfeld writes), he filed an additional request for “any and all” records on former UC-Berkeley president Clark Kerr, former Free Speech Movement leader Mario Savio, and more than a hundred other individuals, organizations and events.

Five lawsuits, many more Magic Markers, and 30 years later, he had succeeded in forcing the release of more than 300,000 pages of records, a federal judge having ruled that the FBI had no legitimate law enforcement purpose in keeping them secret. Rosenfeld, who had a distinguished career as an investigative reporter for San Francisco’s Examiner and Chronicle, supplemented the FBI archive with more than 150 interviews.

“Subversives: The FBI’s War on Student Radicals, and Reagan’s Rise to Power,” the resulting book, is not only about campus surveillance and illicit espionage by America’s top cops but about political causation. Much of it concerns the backstage maneuvers of a right-wing electoral-administrative conspiracy (an accurate word, for once) to subvert First Amendment guarantees of freedom of speech, press and assembly. To clarify: Officials not only collected information, true and false, but they illegally laid hands on history—in particular, assisting the political rise of Ronald Reagan.

|

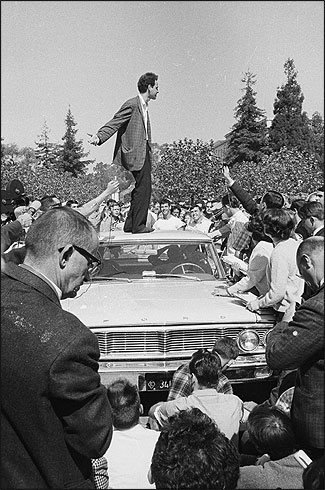

| Mario Savio addresses a campus demonstration in Berkeley, California in 1964. Photo by Steven Marcus. Courtesy of The Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley/Farrar, Straus & Giroux. |

Rosenfeld has produced a scrupulous chronicle and analysis of America’s deep politics, the likes of which exists nowhere else. This writer has long surmised that some of what Rosenfeld reports might be true, but wondered if paranoia was getting the better of him. It was not. The record of the FBI’s obsession and meddling is overwhelming and, across the abyss of time, still shocking. (I should disclose that I read the galley to write a blurb several months ago, but even on second reading, I’m bowled over by what Rosenfeld has found.)

What he uncovered is, to use a word of that era, dynamite. Among the (so to speak) greatest hits are these:

- In 1961, long before a mass student movement erupted at Berkeley, the campus vice chancellor for student affairs was in touch with FBI agents about the campus activist group SLATE. Furthermore, he assured them of his belief that “recognition should be denied to any organization which may have as its motive, open or secret, the discrediting of the university, the Federal Government or any other well-established American ideals”—as if the right to political activity were not a well-established American ideal.

- In 1965, FBI chief J. Edgar Hoover agreed to help the bureau’s “close and trusted friend” Lewis F. Powell, Jr., who was preparing a talk about the Free Speech Movement. The report the bureau prepared for him emphasized the movement’s “subversive element.” Powell, who in his speech to lawyers denounced campus radicals, was later appointed by Richard Nixon to the Supreme Court.

- An FBI informer, who had cut his espionage teeth infiltrating the Communist Party and Socialist Workers Party in Berkeley, procured firearms for the budding Black Panther Party.

- Sharing a political agenda—to root out Communists—the FBI and Ronald Reagan scratched each other’s back for decades, beginning with Reagan’s days in Hollywood. Among other things, the FBI snooped on his daughter at his behest, helped protect one of his sons from scandal, and not least, during his first month as governor of California, met secretly with him to spill intelligence about student protests and help him drive the insufficiently punitive Clark Kerr out of the university presidency. Hoover also helped disqualify Kerr for a cabinet appointment by Lyndon B. Johnson.

There is, as they say, much more. But the story Rosenfeld tells so lucidly and at such necessary length should not be considered ancient history, interesting merely as a quarry for the antiquarian delectation of specialists and veterans. It points to something even more vast and unexplored: presumed troves of evidence concerning the surveillance—unrelated to any legitimate law enforcement purposes and sequestered from public view for decades—of untold numbers of American citizens by government agencies.

In particular, Rosenfeld’s account raises the question of what else the FBI, the CIA, and military intelligence knew about who was doing what in the ’60s and ’70s, when they knew it, and who else they told. No journalist or historian, to my knowledge, has yet mined the FBI archives on Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) and various other antiwar organizations. None have tried to piece together from the individual files of former SDS members (my own are absurdly redacted and backhandedly informative) a coherent account of what the secret police were doing during those years. What did Hoover and his band of monomaniacs in the FBI and other agencies not know? Can it be true that, as archives suggest, the FBI was so clueless as not to have understood until 1968 that the New Left was its own phenomenon and not a front for Communists?

If we are interested in buried truth, it is a matter of urgency to get busy. To put it bluntly, those who were surveilled, infiltrated and manipulated are beginning to pass away. So are those who conducted the surveillance, infiltration and manipulation. To make matters worse, the newspapers that fed Rosenfeld during his years of dogged industry have been cut to the bone.

Is this “ancient history”? Events of those years still cloud American politics. (See: Ayers, Bill.) Conventional wisdom about the past is alive—one may say festering—in the present. Rosenfeld convincingly demonstrates that a picture of the student left from those years that fails to take government operations into account is askew. I write this as one who has long doubted that so-called intelligence operations can, by themselves, explain America’s political fortunes or even the demise of the New Left. I still doubt it. But this is one reason why we need journalists and historians: to unearth what is buried; to doubt our doubt. It’s past time for an onslaught of pro bono legal and journalistic work. Rosenfeld points the way.

Todd Gitlin, professor of journalism and sociology and chairman of the doctoral program in communications at Columbia University, is the author of “The Sixties: Years of Hope, Days of Rage” and most recently “Occupy Nation: The Roots, the Spirit, and the Promise of Occupy Wall Street.” He was the third president of Students for a Democratic Society.