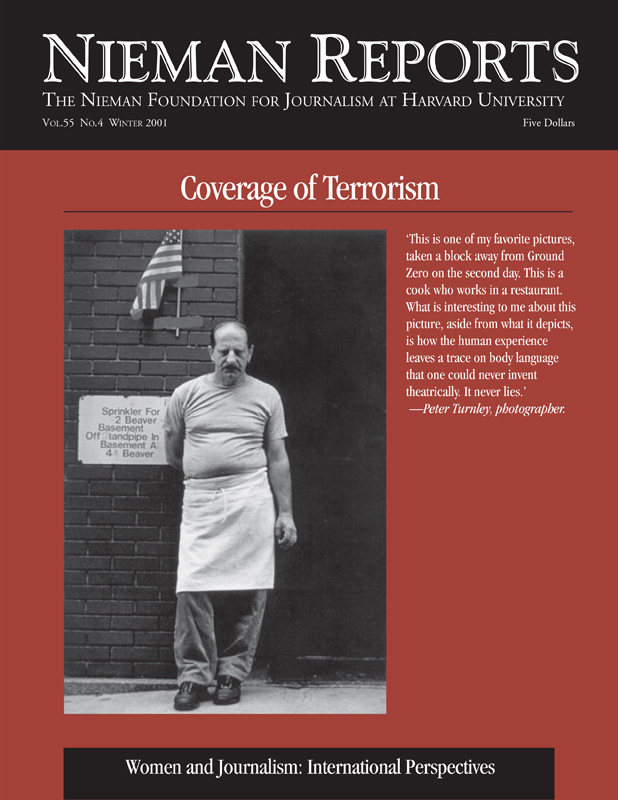

A comparative graph of women’s roles in journalism. Chart by IFJ.

“Women journalists are cracking the glass ceiling, but we must remember that when you break glass you may get scratches from the splinters. Women must be ready to take power in the newsroom; don’t wait for the men to give it to you.”

Dupe Ayayi-Gbadebo, editor in chief and managing director of Sketch Newspapers in Ibadan, Nigeria earned loud and prolonged applause for those comments at a women journalists’ workshop in Lagos at the beginning of November. Dupe Gbadebo knows what she is talking about. At 45 years of age, she is one of three female editors in chief in Nigerian media (none at a major daily newspaper). It took her 20 years to get to the top, and she lost many female colleagues along the way who left journalism for advertising or public relations because they felt they’d never make it beyond sub-editor.

Women leaving journalism is not only a problem in Nigeria. Female reporters from countries as different as Brazil and Belarus report that lack of career perspectives, long hours, and bad pay have driven them to look for work outside journalism. In 1996 a study by the Media, Entertainment and Arts Alliance in Australia found that 23 percent of women journalists had left their jobs because of promotional discrimination.

Women in top media positions remain a rare breed even though the number of women in journalism has been growing steadily. In 1991, a study by the International Federation of Journalists [IFJ] found that 27 percent of journalists were women; today they represent 38 percent of the profession, but there are large discrepancies among various countries. For example, the percentage of women journalists in countries such as Finland and Thailand is close to 50 percent, but in Sri Lanka and Togo, it is six percent.

A study published this year by the IFJ found that even though more than a third of today’s journalists are women, overall they comprise less than three percent of media decision-makers. Their percentage is higher in North America and Latin America. In Mexico, for instance, 19 percent of media owners or editors are women. In Asia, the percentage of female media executives is the lowest and barely perceptible.

Female journalists still have to overcome many barriers if they want to reach their full potential in the profession. The list of obstacles is long and it is the same whether drawn up by women journalists in Asia, the Pacific, Latin America, Africa or Europe:

- Stereotypes: cultural attitudes expecting women to be subordinate and subservient and negative attitudes towards women journalists;

- Employment conditions: lack of equal pay, lack of access to further training, lack of fair promotion procedures, lack of access to decision-making positions, sexual harassment, age discrimination, and job segregation;

- Social and personal obstacles: conflicting family and career demands, lack of support facilities, and lack of self-esteem.

The stories of women journalists who make it to the top are often ones of personal struggle and sacrifice. But these pioneers do inspire younger women to follow in their footsteps.

“Without Najma Babar I would not have stuck with journalism,” says Beena Sarwar, editor of The News on Sunday in Pakistan. “She was my role model when I started at The Star in 1982. She was not only a real professional but she also put women’s issues on the news agenda. Without her, the story of trafficking of women from Burma and Bengal would never have been covered.”

Angela Castellanos, a freelance journalist from Colombia, observes that “courageous women reporters have made real inroads into a profession characterized by machismo. But we have paid a high price for recognition. Last year, two female journalists were killed, 11 were threatened with murder, three had to seek exile abroad, and one was kidnapped and tortured.” That journalist was Jineth Bedoya, a 27-year-old journalist working for El Espectador who was kidnapped, tortured and raped by paramilitary groups. In spite of her ordeal, Bedoya stills works in journalism. She says she was lucky to have the support of her editor: “Normally in Colombia there is no support for rank-and-file journalists, only for the famous ones.”

But it takes more than a few pioneers to make a real difference in dismantling the barriers that women journalists confront. The role of journalists’ unions is crucial in defending the professional and material interests of their female members as well as helping to create structures in which women can reach their full potential in the profession. As the number of women in journalism grows, so does their membership in journalists’ unions. In several countries in North America and Latin America there are more female than male union members (around 55 percent). And the percentage of women in union governing bodies (17 percent) is higher than of women in decision-making in the media in general.

But for journalists’ organizations to take up these issues, they often have to reform their structures to ensure female representation in the unions’ policymaking and governing bodies. One way to increase the involvement of women is to create specific structures, such as women’s committees or equality councils, to give women’s concerns a voice in the union. “It is thanks to the equality council that parental leave or day care have become key demands in collective bargaining,” says Karin Bernhardt of the German Journalists’ Association (DJV). “These issues used to be bargaining chips to be dropped off the list of demands in favor of higher salaries. The work of women inside the union has helped to make employers and male colleagues see that extended parental leave can be much more important than a few dollars more in the purse.”

But so far less than half of the unions surveyed by the IFJ have established women’s committees or councils. The highest number is in Africa, where women’s media associations have been created in most countries. These associations operate independently of the journalists’ unions but are normally affiliated with them. “The women media association has become an effective network for women journalists,” says Khady Cisse, who is also a member of the board of the journalists’ union in Senegal. “It is through the association that we have been able to discuss issues like portrayal of women and sexual harassment.”

Outside of Africa, the model of women media associations or committees has started to take root. Women journalists from Asia, where the level of representation is lowest both in the profession and in the unions, agreed at a conference in Japan last year to create women’s networks to promote their cause. As far as Ezki Suyanto, producer of the “Voice of Human Rights” radio program in Indonesia is concerned, this step is long overdue: “Women must get together and claim their rights. Why do they remain silent if they want more responsibility?”

The issue of portrayal of women in the media remains a much-debated one. The U.N. Beijing declaration, adopted more than five years ago, called on media owners and media professionals to develop and adopt codes or guidelines to promote a fair and accurate portrayal of women in the media. An IFJ report prepared for the UNESCO conference on “Women in the Media: Access to Expression and Decision-Making” (Toronto 1995) found that: “…after more than a decade of research indicating that women are dissatisfied with their media portrayal, the industry has done little to change its practices. Women are grossly underrepresented and, where they do feature, they are still portrayed in a narrow range of stereotyped roles.”

The IFJ survey aimed to get the unions’ point of view on this issue and asked whether IFJ unions felt that the portrayal of women in the media was an issue for them and what actions could be undertaken to promote an accurate and fair media portrayal of women. Close to half said portrayal was an issue and one being discussed within the union. Those who do not discuss it gave different reasons for the lack of debate in the union. One union in India said that since a free press exists in the country, the issue of portrayal is not a pressing one. Several unions (in Benin, Austria, Bosnia-Herzegovina, Croatia, Bulgaria and Paraguay) stated that other concerns are more important, such as basic violations of labor and human rights or that other groups exist that take up the issue. The Japanese unions said given the low number of women members, the issue had not yet made it on the union’s agenda of priorities.

One-third of the unions surveyed said stereotypes or the presentation of women according to prejudices that do not correspond to reality are the main reason for an inaccurate portrayal of women in the media. About one-quarter of the unions said the lack of female sources, experts or spokespersons in media coverage accounts for a distorted image of women in the media. Another 20 percent believed that the media do not sufficiently cover issues of concern to women or report reliably on their perspectives on development in society.

Journalists and media organizations might disavow responsibility for the non- and mis-representation of women. This issue is but one aspect of the general debate about quality of content in media. There is little doubt, however, that media professionals, whether they own the newspapers and broadcast media or are employed to gather, edit and disseminate information, have an urgent need to articulate principles of better performance and make themselves ethically accountable in a transparent and public manner. Such resolve should apply to challenging media stereotypes of women, as much as it applies to efforts put forward to challenge intolerance and hate speech.

IFJ has explored the role of journalists’ unions in defending the professional and material interests of their female members.

A page from the International Federation of Journalists’ Web site.

Bettina Peters is director of the International Federation of Journalists’ Project Division.