Photo by Diedra Laird, The Charlotte Observer.

For years, parents and educators in poverty-ridden pockets of the South sensed the public schools were shortchanging their children. And they were right. Their schools face numerous challenges: Administrators and teachers must educate some of the region’s most disadvantaged students, children whose home and community environments often don’t have the ability to support them in pursuit of a rigorous education. These deficits are accentuated by the inability of poor districts to raise local tax dollars needed to provide the kind of resource-rich schools found in wealthier districts.

In 1998 The Charlotte Observer set out to document the educational disparities among rich and poor school districts in North and South Carolina. We did this by illuminating the lives of children and families as they confronted the circumstances of their local public schools, but we also brought to this investigation a fresh analysis of data about how students and schools were performing. This data included comparisons of test scores, rates of teacher turnover, and a host of measures that researchers conclude are key to children’s academic success. Our analysis gave us a way to present to readers the stark reality of what happens when poor children don’t have access to a quality, competitive public education.

We spent eight months tracking down local, state and national reports that would help us show how the economic gap in public investment impacts student achievement. We developed databases and spreadsheets so we could EDITOR’S NOTE

Read an on-line version of the series in The Charlotte Observer »get a better handle on the dynamics of our region. We wanted to portray the stark contrasts between wealthy and poverty-plagued systems and help readers see more starkly than they had before the saddening failures that were the unfortunate hallmark of our poorer public schools. The result was a series called “The Price of Hope,” published August 16-20 in The Charlotte Observer.”

Our series began with a teenager named Quanda Edwards, who wants to go to Harvard but is growing up in a school system without such basics as advanced placement classes. Our story also included comparisons of the financial gulfs between each state’s richest and poorest school systems. The basic measure was wealth per student, an estimate of the local tax money a community could afford to spend if it levied a state average tax rate. This yardstick—basically a measure of a community’s ability to support schools—was created by the North Carolina Public School Forum, which has long studied school finance. The South Carolina Department of Education provided its tax data, which we used to create a measure similar to what we were using in our state.

According to this measure, Mecklenburg, The Observer’s home county and one of North Carolina’s wealthiest school systems, could afford to spend an estimated $5,529 per student. In contrast, the state’s poorest county, Hoke, could afford to spend only $708. A similar gap appears when one looks at the actual dollars spent on education. In Mecklenburg, spending per student in local taxes was estimated at $2,271, compared with $563 in Hoke. With this information, we could also see that the ratio of spending to wealth is about twice as high for Hoke (0.8) as for Mecklenburg (0.4). This suggests that Hoke, although it is much poorer, is expending significantly more taxation effort for its schools, even though the amount generated is meager.

Given these disparities, it was perhaps not surprising as much as it was disheartening to learn how students were faring in poor schools. Among other things, our investigation found that students in the 15 poorest districts in each of the Carolinas post an average combined SAT score that is 100 points lower than their peers in the wealthiest systems. Teachers in the poorer schools are less likely to hold higher-level degrees, and students are less likely to take gifted or advanced placement classes or attend college. And those who do get to college are more likely to need remedial help.

Students from poorer counties are also less likely to perform at grade level in reading and math, a situation that our data were able to convincingly describe. In each of the Carolinas, the 15 poorest school systems post test scores that repeatedly pull both states down on national education measures, such as the SAT.

On our Web site, we offered demographic and educational profiles of every North Carolina county and South Carolina school system so our readers could explore these patterns in detail. Many people had heard something about the plight of poor school systems and about terms like “educational equity,” so this gave readers a chance to see the relationships among these factors.

Poor districts in each of the Carolinas had filed lawsuits asking for new ways to be created to raise more money. These cases are similar to many that have been heard by courts in other states. In North Carolina, the state Supreme Court has ruled all students have a right to a sound, basic education. At the time our series ran, lawyers were scrambling to determine just what it would take to provide a “sound, basic education” to all students. The South Carolina case is still pending.

The Observer wanted to help readers better understand what those lawsuits were about. Beyond helping them to corral the facts, we wanted to introduce them to students, teachers and parents whose lives and futures were directly impacted by the poorer schools’ inability to afford what most would consider to be the basics of education at the end of the 20th Century—advanced placement classes, well-equipped computer labs, teachers trained in how to use these new education tools, and programs for the gifted.

To tell these stories, I (reporter Cenziper) and photographer Gayle Shomer traveled the back roads of North Carolina to spend time in rural school systems where our data told us that students were producing consistently low test scores as their towns struggled with issues of chronic low funding. We wanted to rely not only on our statistical analysis, but on real people and their stories.

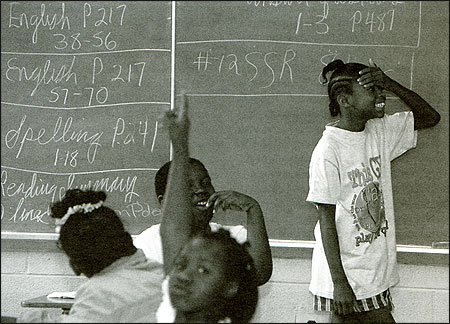

Our first stop was the city of Weldon, an old railroad town in a poor northeastern region of the state. There, in a middle school made up almost entirely of mobile classrooms, we met Quanda, an eighth grader who wants to become a lawyer, attend Harvard and build her own house. She’s a high achiever in a school where, our data let us know, teachers don’t often return after summer vacation. As is true in so many other poor school systems, teacher turnover is severe, and when teachers come and go from a school, student performance tends to suffer.

When Quanda gets to high school, she will not be able to take advanced placement classes because the system doesn’t have the money to offer them. Weldon City High has no school newspaper, no yearbook, no electives such as psychology or chorus or photography. There are no school plays because there is no drama class or teacher. No one in the last graduating class had gone on to an Ivy League school, and it’s been a rarity for anyone to do so.

Still, Quanda is not worried: “I am very confident in myself, and I have my friends and my family there for me whenever I need them.… As long as I have that support, and, you know, I believe in myself, to me, right now, I’m sitting on top of the world.” Can her confidence and support get her over the hurdles created by all that her school system lacks?

From Weldon, The Observer staffers moved south to Harnett County, where they spent time with rookie teacher Kathy Harding. In poor school systems, successful teachers like Harding often move on for higher-paying teaching jobs in wealthier counties. In Wake County, for example, our data showed that Harding would make $2,000 more a year; and $2,700 more a year in Mecklenburg. In a typical year, Harnett schools will have to fill 130 of 670 teacher jobs. Harnett school leaders hope Harding will stick around but they can’t provide financial incentives. Harding loves teaching, but she becomes exasperated when she thinks about teachers elsewhere who earn higher pay for jobs that might be much less challenging than hers. “You do the exact same things they do. I have the same degree. I’ve been to school for four years. I’m a hard-working person. I show up every day. It doesn’t make any sense just because we’re a few miles away, we make less money,” she told our reporters.

The Observer’s next stop: Anson County, just east of Charlotte, and home to Debbie Smith. Debbie, who never got to finish college, dreams that her four children will. She started putting money into college funds years ago. But Debbie is worried Anson County schools won’t prepare her kids for the demands of higher education. Three of her children attend Morven Elementary, where the academic challenges are among the most formidable in the state. Though test scores are improving, less than half of the students who attend that school are reading at grade level. Only 38 percent of the fourth graders passed the state writing test. “I know beyond a shadow of a doubt that principals and teachers here are doing everything possible with the resources they have,” Smith says. “But with more money and more resources, everything could be a whole lot better.”

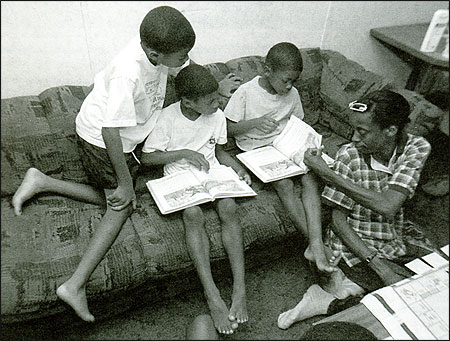

In South Carolina, Observer reporter Jonathan Goldstein and photographer Diedra Laird traveled to Lee County and met Diane Davis. Her four children hunt for books in a half-empty library at West Lee Elementary School. They wait in long lines to use a computer. They tumble through physical education lessons in a musty trailer behind the school. Although rich-poor differences exist in every state, critics say the situation is consistently worse in South Carolina, which spends less state money per pupil than neighboring states.

Many readers responded to our series, offering advice and donations for poor schools. One of the state’s most vocal education advocacy groups is using the findings in our series to try to mobilize members of the public to bring about change. An Observer poll taken just before the series ran showed 71 percent of Carolinians are willing to shift tax money from wealthy to poor systems. Several measures were recently put into motion among legislators to bolster poor schools, including one that boosted from about $50 million to $60 million the supplemental fund that is used to aid low-income and poor school systems.

“The Price of Hope” took our readers on a well-documented journey into the educational plight of children and families whose lives aren’t often covered in our newspaper. By compiling and analyzing data, then finding the human stories to illuminate the various tales our numbers told, we were able to produce a unique and valuable series about a vitally important issue of public policy and debate.

At her home in rural Lee County, Diane Davis helps her sons with their homework. Photo by Diedra Laird, The Charlotte Observer.

Quanda Edwards, 13, left, listens with classmates to school test scores being announced at Weldon Middle School. Photo by Gayle Shomer, The Charlotte Observer.

Database Editor Ted Mellnik leads The Charlotte Observer’s computer-assisted reporting program. Debbie Cenziper is the paper’s education reporter who also reported on schools and social issues for The (Fort Lauderdale) Sun-Sentinel.