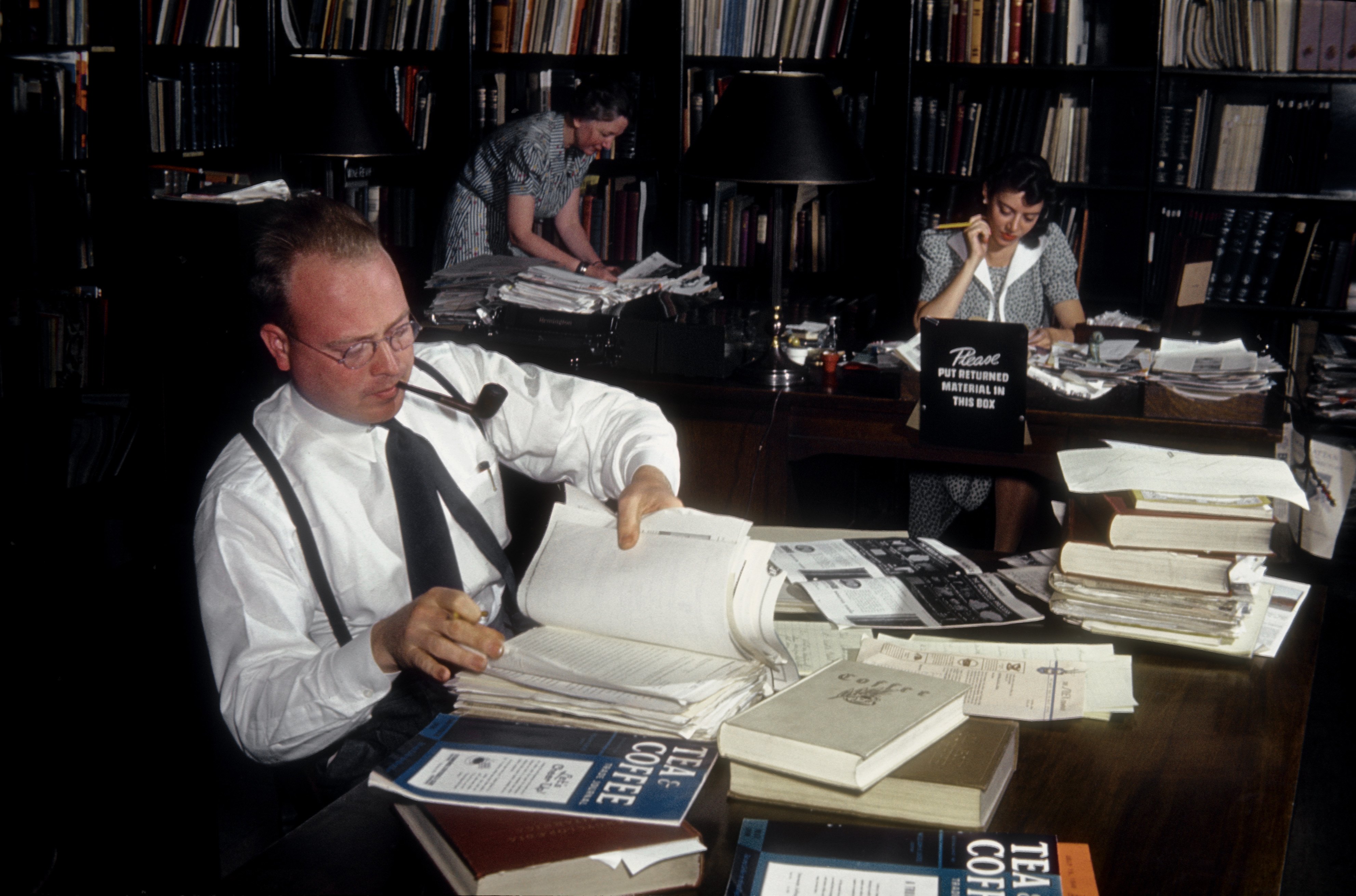

A Madison Avenue advertising executive works on a project circa 1950

While covering the media business for The New Yorker for more than 25 years, Ken Auletta has profiled many of the most important leaders of the Information Age and reported on the disruption roiling the industry. Among his books are “Three Blind Mice: How the TV Networks Lost Their Way” and “Googled: The End of the World As We Know It.”

In the introduction to his twelfth book, “Frenemies: The Epic Disruption of the Ad Business (and Everything Else),” published by Penguin Press on June 5, he notes that the flight of advertisers from old to new media which started in the late 1990s has accelerated in the current century. “In the public imagination, we were still in the age of Don Draper, but I began to see more and more clearly how this industry that had been intrinsic to the disruption of old media was itself facing fundamental challenges to its existence.” He writes, “The once comfortable agency business is now assailed by frenemies, companies that both compete and cooperate with them.” For the advertising and marketing sector, worth up to $2 trillion, these are anxious times.

An edited excerpt:

Whatever form advertising and marketing takes in coming years, a certainty is that data-fed targeting will be a pillar. Irwin Gotlieb, chairman of GroupM, a subsidiary of W.P.P., believes that in the future, agencies will have to guarantee results to clients, and better results will boost agency compensation.

“Frenemies: The Epic Disruption of the Ad Business (and Everything Else)” by Ken Auletta (Penguin Press)

We can also be certain that privacy will remain a third rail to marketers, always worried that governments will grow alarmed and impose regulations. The European Union, for example, passed legislation restricting the ability of companies to collect personal information without the user’s consent.

Some, like Andrew Robertson of BBDO, believe that the blizzard of different platforms and better targeting will place a premium on creative advertising that captures people’s attention and will invite advertisers to spend more to lure those identified as potential customers, as advertising spending becomes more cost effective. Others, like MediaLink CEO Michael Kassan, offer a bleaker view. “My biggest fear is that the inextricable link that existed historically between serving up content financed by commercial messages, that link is broken because consumers can get their content without commercials now. Think what it would have cost you to get Life magazine if there were no ads in it. It was subsidized by advertising.” But today too many people “just won’t watch commercials.”

So what replaces the commercials?

“We will live in a subscription world,” he boldly, and I believe wrongly, answers.

Tim Wu is among the most prominent advocates for replacing ads with subscriptions. Harking back to 1833 and the first ad-subsidized newspaper, the New York Sun, he calls this “the original sin.” In his provocative book “The Attention Merchants,” Wu argues that in advertiser-supported media the reader or viewer is not the customer; the advertiser is. Thus, letting advertisers into the tent inevitably means a diminution of quality, because advertisers pressure the platform to deliver a bigger audience. More news about Kim Kardashian magnetizes an audience. The way to improve media is to pay for it, he says, preferably with subscriptions and micropayments. Wu is not alone. In February 2017, Twitter cofounder Evan Williams, who had raised $134 million to improve journalism by forming Medium, an ad-supported blogging and publishing site, announced that he was laying off one third of his staff and ending its reliance on ads. Echoing Wu, he told Business Insider that ad-driven media was “broken” because corporations fund it “in order to advance their goals. … We believe people who write and share ideas should be rewarded on their ability to enlighten and inform, not simply their ability to attract a few seconds of attention.” When Jim VandeHei left as CEO of Politico in 2016 to start a provocative online publication, Axios, he assailed the “crap trap” of “trashy clickbait” designed to attract more page views and thus to satisfy advertisers. The “trap” was set by a reliance on ads. For Axios to produce quality journalism, he said, “readers will have to pay up and if they need and love the product, they will, and gladly so.”

The thoughts are noble, the analysis of what often ails advertising-supported content is correct. But the economics don’t support the noble idea. The economics of Axios certainly doesn’t support VandeHei’s bold words, for roughly 90 percent of Axios’s revenues, one of their principal investors says, comes from corporate sponsorships, or advertisers who are granted a sandwiched paragraph and often a picture introduced with headlines like this: “A MESSAGE FROM BANK OF AMERICA.” Hillary Clinton and Donald Trump didn’t agree on much in the 2016 presidential contest, but they did agree that most Americans in the middle were being squeezed, their incomes frozen. Although median income did rise between 2014 and 2015, it was little changed from the pre-recession year 2007. The Census reports that median household income in 2009 was $54,988; by 2015 it had inched up to only $56,516. And those just below median income but above the poverty line saw their income drop. The Brookings’s Hamilton Project found that, after adjusting for inflation, wages in the U.S. rose just 0.2 percent over the past forty years.

Think about the subscription toll today, including mobile phone, broadband, cable or satellite TV, newspaper and magazine subscriptions, Netflix, HBO or Showtime, Amazon Prime, apps, music. Jeffrey Cole, who teaches at USC, says the average household pays monthly subscription charges of $267 per month, which does not include electricity, gas, and other unavoidable monthly bills.

How do most overstretched consumers pay more? They probably don’t. There are, of course, successful efforts to reduce dependence on advertising. Hulu is growing its subscriber base. The Apple App Store rang up $2.7 billion in subscriptions in 2016. Spotify’s subscriber base swelled from thirty million to fifty million in 2016. Amazon’s Prime membership, for a modest annual fee of $99, offers an estimated 100 million subscribers free delivery, free streamed movies and television shows, free music, and other enticements. The New York Times’s reliance on advertising revenue has been cut from 80 percent to about 40 percent. (But unlike most newspapers, the Times like the Wall Street Journal and the Financial Times—could pull off this feat because they successfully raised the subscription price and their affluent readers were willing to pay.)

Some novel experiments to lessen reliance on advertising have also been tried. Rather than impose a paywall to deny free online access to news stories, a practice followed by most newspapers, the Guardian provides open access. But at the bottom of each story they append this:

Since you’re here . . .

… we have a small favour to ask. … If everyone who reads our reporting, who likes it, helps fund it, our future would be much more secure. For as little as $1, you can support the Guardian. …

Readers can then click on a credit card or PayPal link. A total of 300,000 readers volunteered a contribution, the Nieman Lab reported in November 2017. Another 500,000, they reported, either joined various membership programs for a monthly fee granting them access to various events and newly published books, or were print or digital subscribers. These monies now eclipse the Guardian’s ad revenues. (Nevertheless, the Guardian is still bathed in red ink, losing $61 million in fiscal 2016–2017.)

For those not wanting to see ads, YouTube offers Red for $9.99 per month. Many other platforms charge extra to be free of commercials. It is not uncommon to hear the argument advanced by entrepreneur Kevin Ryan, a founder of DoubleClick and Business Insider: many could afford new subscriptions because they “are going to Starbucks and paying five dollars a day for a coffee.”

To believe that the bulk of consumers who live on tight budgets can afford subscriptions as a substitute for the ad dollars that subsidize most of our “free” media and Internet activity is to ignore the math

Maybe. But let’s return to the economics. The New York Times’s subscriber base is expanding nicely, up by 46 percent between 2015 and 2016. They, like the Washington Post, have done a spectacular job puncturing the untruths and disarray of the Trump administration, and they’ve been rewarded with a burst of new digital subscribers. These subscribers have made the Times less reliant on ad dollars. This is great news. But, and here’s the rub: the Times makes most of its profits from the print newspaper, including 62 percent of its advertising revenues. And it’s not clear how a much-cheaper-to-produce digital newspaper could generate comparable ad revenues.

Why? The average reader of the print edition of the Times spends about thirty-five minutes a day with it. But the average online Times reader spends about thirty-five minutes a month. Because advertisers know readers spend much less time looking at their ads, they pay about 10 to 20 percent for the same online ad as appears in the newspaper.

Despite the growth in digital subscribers, and the rise of circulation revenues of 3.4 percent, and the growth of digital ad revenue of 5.9 percent, the overall revenues and profits of the paper fell in 2016. This left the Times to caution about its future in its 2016 annual financial report, “We may experience further downward pressure on our advertising revenue margins.”

By the end of the third quarter in November 2017, the Times reported that despite the further erosion in print newspaper revenues, overall revenues rose by 6 percent. Obviously, if the Times could one day abandon its print edition, the cost savings in paper, printing, and distribution might offset the disproportionate profits the print paper generates. Or if the Times can increase its subscription revenues from 60 to 70 percent, as it hopes it can, analyst Ken Doctor has written that the Times could escape from its struggle to maintain slim profits to “generate actual, lasting growth, ahead of inflation.” Alas, Times profits in the years ahead will be slim. And like other smart analysts, Doctor knows that if the Times succeeds in maintaining slim profits, it will be an aberration, not a trend for other newspapers. The dominant trend was defined by Gannett’s USA Today and its 109 regional newspapers, and chains like McClatchy and A. H. Belo, which saw their 2017 print advertising and circulation losses exceed their digital advertising and subscription gains.

No question: consumers can reconfigure their cable bundles and can make choices among various subscription models. But to believe that the bulk of consumers who live on tight budgets can afford subscriptions as a substitute for the ad dollars that subsidize most of our “free” media and Internet activity is to ignore the math.

Yet the conundrum is that the advertising ATM machine subsidy may also be unreliable. The thought many marketers try to banish is whether for consumers-spoiled by Netflix and YouTube, by ad-skipping DVRs and ad blockers, by personal devices we hold in our hands—the interruptive ad message may be a relic. Are consumers irrevocably alienated by sales pitches? Has the consumer, on whom marketing relies, become a frenemy?