Protests against the Indian occupation of Srinagar, Kashmir grew more violent after members of India’s security forces allegedly raped and murdered two young women in late May. When Marcus Bleasdale visited in July, angry residents clashed with Kashmir’s own police force as well as the Indian security forces. At one point, he watched as large waves of youths advanced toward the police, using the metal ripped off the sides of shops and market stalls as weapons and projectiles. Live rounds were fired and youths threw a grenade at a group of Kashmiri police, killing three and wounding seven. Tens of thousands of people have died over the past two decades of insurgency in Kashmir.

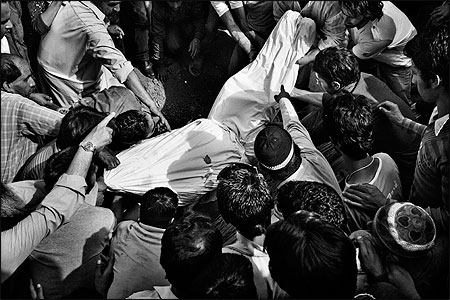

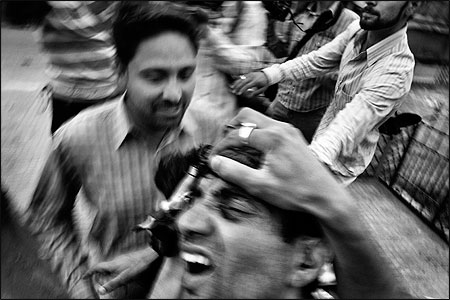

Riots are frenzied and dangerous. In Kashmir—a disputed region where India and Pakistan clash and an armed insurgency roils longstanding tensions—locals want an independent state but politicians in both countries deny them the chance to vote on this issue. So daily on the streets rocks drop from all directions and security forces fire tear gas and rubber bullets at the crowd of demonstrating youths. There is always a randomness to the shots, from left and right, in the air and on the ground, and with this comes danger.

When shooting pictures at a time like this, there is a split-second chance to make a frame that reflects my feelings about what I am witnessing—the craziness of the environment and pain and danger that are ever present. I am aware of all of this happening around me, but at the same time I try to push it out of my mind and concentrate on small moments—the emotions and the composition to express them—and try to make us all understand and almost feel we are there when we look at the images. I seek to represent the reality of what is happening.

In these moments, I am never sure whether I will be hit, arrested or shot. I just shoot and hope the violence passes me by. The noise is deafening—the guns firing, the screaming. Orders from the military echo all around, as do their guns aimed at the youths. I duck and wince, not always sure where the gunshots are coming from. It is instinctive. I know if I heard the shot then I am fine, but still I duck away from the source of the noise in the mistaken hope that this will protect me.

The children demonstrating in Srinagar, the capital of the state of Jammu and Kashmir, were so young. The local graveyards are full of the bodies of those who fought before them, but still they fight. In watching them, I can’t help but think of my niece and my nephew who are about the same age as many of the demonstrators. Could they be doing this? How would I feel if they subjected themselves to these dangers? Here, families accept it as one would accept children running to the park to play for an hour because their anger at occupation is so acute.

Elder brothers and sisters consider these young demonstrators to be heroes. Many times I saw older brothers proudly presenting their young brothers as fighters against occupation. Yet when I asked them about the history of the conflict, they seemed to know very little; their motivation for getting involved with these dangerous activities was comradeship and “something to do.”

Sometimes they play in front of the lens. When they do this I walk away. I am not there to create a moment that would not otherwise exist. Yet this can be a problem for those of us who come to tell this story with our cameras. Sometimes I see journalists filming and shooting a riot or demonstration and I have the sense that it would not exist without the camera being present. In not wanting to be a part of this problem, I tend to hang back away from the demonstrators, jumping into the action only when I sense things are more natural and honest.

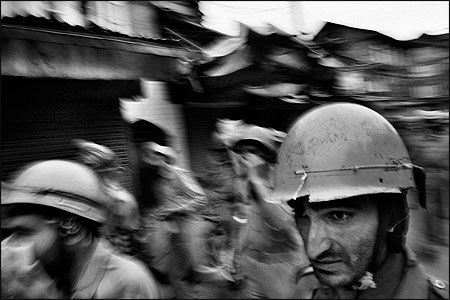

War is seldom well executed. There is panic and fear, indecision and decision; events consist of noise and silence at the same time. To be inside of it is to experience a rush of thoughts and emotions, cascading from the ultimate high to the deepest low, then up and down again. Soldiers, tunneled in their vision, seemed nonetheless scared about what’s going to happen in the next 30 seconds and indecisive about how far they should go to enforce their will and the will of their commanders. This mix of feelings and thoughts and emotions—fear, panic, the rush of the moment—is what I want to visually capture.

As I run with the security forces advancing to get into position, I can feel the fear that surrounds me. I try to carry this feeling into my work of capturing this crazy moment of unknowns. How far will the troops go? What will they decide to do once the two sides are engaged? Will they live? Will those demonstrating survive? What I seek is the visual representation of this undefined line between human emotion and the reality of war.

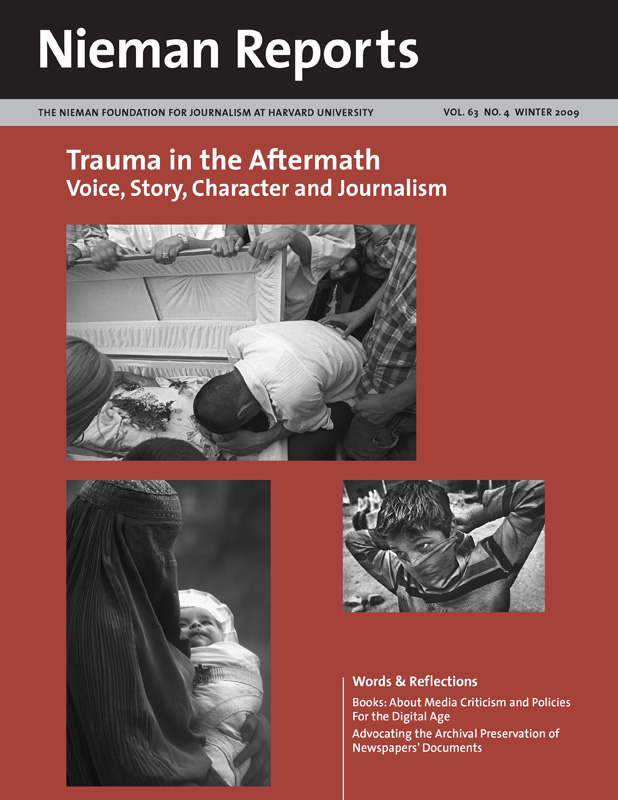

In experiencing death, each of us reacts differently. Nor can any of us know how we will absorb the sudden death of a loved one until it happens. In our minds, some of us see ourselves weeping and collapsing, others as strong-willed and stoic in acceptance. Rarely do we regard death as tossing us into a mixed-up, overpowering emotion that takes full control of our body and mind.

Saying goodbye to a loved one, is, one hopes, a dignified affair that gives us time we need to reflect, think and pray for those whom we have lost. Time to understand why things like this happen. During war, it is often not possible to have that reflective time to say goodbye. Funerals are rushed as the war goes on. Anger manifests itself into further protests and more death, and a question must be asked: why does one more youngster’s life get sacrificed in this cycle of retribution for the young lives already lost?

Photographing these moments is enormously sensitive. I have at times been asked to document these moments for a family so angry at what has happened to them. They invite me into their homes and their hearts at the most emotional time. It’s overwhelming, and yet in some strange way I’m honored by this privilege. The family trusts me. They ask me to be their voice, to record this moment in the vain hope that their child will be the last life that is lost.

I try to be quiet and discreet. Once a father spoke to me over the body of his son. He told me about his child and how he was such a good boy with such a future. He loved life and his family, and he loved cricket. His tears dropped onto the coffin and I listened. This was not the moment to raise the camera; this was a moment to talk, to pray. A few minutes later his head slumped on the coffin—I remember it like yesterday—my hand and my camera rose and I pressed the shutter. The tears rolled onto the lid of the coffin and the family prayed.

Marcus Bleasdale has spent 10 years covering the conflict in the Democratic Republic of Congo and has written two books, “One Hundred Years of Darkness” and “The Rape of a Nation.” His photographs are widely published in Britain, Europe and the United States. He won a first-place award from Pictures of the Year International in 2009 for his photographs documenting human rights abuses in Congo. His photographs from Kashmir appear on this page.