|

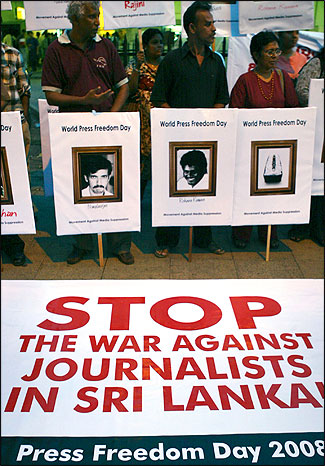

| Sri Lankan journalists display portraits of colleagues who have been killed. Photo by Eranga Jayawardena/The Associated Press. |

After living in Japan for decades, I returned to my native Sri Lanka in 2007 for a new job. It was no ordinary homecoming. I moved to the capital city of Colombo to be director of the local office for Panos South Asia, an institute that aims to foster democratic, just and inclusive societies by working with the media. I remained there for nearly three years, working with local journalists at a time when a civil war was devastating the nation.

It is only now, months after I returned to my home in Tokyo that I have realized just how unprepared I was for my stay in Sri Lanka. At the time of my assignment, I had spent about 25 years—or more than half my life—in Japan. Yet Sri Lanka—with its natural beauty, my childhood friends, former journalist colleagues, and an army of relatives, with whom I had remained in close touch over the years—was not unfamiliar to me. No, what I’m referring to is how unprepared I was to be part of a society that was in the throes of a violent ethnic conflict spanning more than three decades. Having been out of the country for most of those years, I had been spared the horror of the military shelling and the ground battles that consumed the daily lives of civilians in the north. And in the rest of the country, grinding uncertainty faced people who worried endlessly about falling victim to the terrorist bombs that destroyed public places from time to time.

I was not unaware of these hardships and I felt great empathy for my family, friends and fellow Sri Lankans, but the hard truth was that I had not grasped the emotional complexities that had developed during a long period of war and how they affected ordinary citizens, such as the generation born after 1983 that has never known peace. This meant acknowledging media censorship as well as self-censorship, the rising appeal of nationalism, the ugly polarization between ethnic groups, and a public wariness toward foreign entities and their local partners that were mainly civil society organizations advocating a peaceful solution.

A History of Conflict

The island of Sri Lanka lies like a delicate pearl in the Indian Ocean with just 18 miles of sea separating the northern end of the country from the Tamil Nadu state in India. Historically, Sri Lanka was ruled by three kings. A Tamil king presided over the Hindu north, and Sinhala kingdoms dominated the southern and central regions of the island. British colonization united the country for more than 100 years until Sri Lanka obtained independence in 1948 and installed a parliamentary democracy.

Sri Lanka has seen many periods of ethnic rioting, including attacks by Sinhala mobs on Tamil civilians. Seventy-five percent of the 21.5 million residents of Sri Lanka are Sinhala, 14 percent are Tamil who share cultural similarities with southern India, and 8 percent are Muslims who speak Tamil; other ethnic minorities make up the rest of the population. Under the majority rule of democracy, some elections have threatened minority aspirations for equal language and cultural rights. Several key political decisions, such as creating a Sinhala Buddhist state, have been particularly traumatic, especially for the Tamil-speaking minorities. These ethnic tensions led to a violent armed struggle for a separate Tamil state in the north that ended with the defeat of the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE) militant group in May 2009 after several failed attempts at a negotiated peace. The war was bloody on both sides, with the United Nations estimating the death toll at 80,000 to 100,000.

When I arrived in Colombo, the public overwhelmingly supported the government’s promise to finish off the Tamil Liberation militants militarily and as quickly as possible. Mainstream media—newspapers and television—leaned heavily toward state policy. The few media outlets that highlighted possible peaceful alternatives to a military onslaught in the north or gross human rights violations were not popular. A large number of the Western-educated English-speaking elite that dominates Colombo had thrown their support behind the war. In the capital’s cafés and elegant drawing rooms open criticism of the state was soundly rejected on the funny logic that war must be won at all costs.

A Question of Language

Just a year into my work, I discovered that I had been labeled a “terrorist sympathizer,” a slogan that was easily slapped on anybody considered to be opposed to the state war. One reason for this unwanted title was my sympathies, expressed openly, for a negotiated settlement. In addition, the fact that I have a Tamil name raised suspicions among the Sinhala majority. My insistence on conducting workshops and seminars for journalists on themes such as respecting diversity and minority rights did not contribute to easing the baseless criticism. Friends cautioned me as they read stories filed by local journalists who had joined the patriotism bandwagon, and, as was the norm, portrayed any whiff of dissent against the war as a Western conspiracy. Stories suggested that international calls for a peaceful end to the war amid the rising number of fatalities were aimed at upsetting the security of the country, a viewpoint readily supported by a hard-pressed public waiting eagerly for the quick end to the war that the government promised.

I now wonder if I could have done things differently. For instance, there were endless discussions between like-minded groups on whether we should talk of “development” instead of “peace.” Which word would ease the pressure from the authorities, we wondered. Would it have been wise to stop referring to the “rights” of minorities and use the more subtle expression “expectations”? Or is it best to throw caution to the wind and face intimidation head on? Such questions are pertinent for journalists especially today when they face the prospect of toeing the line to save their jobs in paternalistic hardliner regimes or, in capitalist nations, becoming mouthpieces for wealthy owners who are taking over economically strapped news organizations. These situations demand new survival tactics and a serious debate on the crucial issues facing journalists in nations that prohibit the press from presenting evidence or controversial opinions while espousing the view that a free press is a detriment to nation-building. Against such a backdrop, determining how journalists can best meet the challenge of remaining true to the values of their profession is of utmost importance.

Suvendrini Kakuchi, a 1997 Nieman Fellow, is the Tokyo correspondent for Inter Press Service news agency. She spent nearly three years as the director of the Sri Lankan office of Panos South Asia.