Covering Hurricane Katrina was definitely not a class project—not then and certainly not now. It was a test of sorts for me and for my patience and skill as a photojournalism professor.

One day, at the beginning of fall semester, I was walking up the steps of the Jesse Jones Communication School building when I started to wonder where one of my students, Ben Sklar, was hiding himself. He is the president and founding member of the University of Texas at Austin National Press Photographers Association student faction, and I am its faculty advisor. Then I saw a middle-aged woman blocking my path. Her eyes conveyed the sense of someone searching for answers. She was Susan Sklar, Ben’s mother, and she introduced herself to me and succinctly related her story: Ben had just completed an internship at a Jacksonville, Florida newspaper and was supposed to return to Austin for classes and an internship at the Austin American-Statesman newspaper. Now his mother couldn’t locate him.

It was worse than that. In spite of his mother’s admonition to avoid the hurricane, Ben, a photojournalism student, had gone directly into its path. His mother was not only worried that he would fail to complete his internship or graduate next May, but she was terrified now for her son’s safety.

I understood her fear. At that moment, I felt as if I were a parent, too, as I watched my children—my students—bursting with the desire to run out and join the real world. Mark Mulligan, Sloan Breeden, Meg Loucks, Rob Strong, and Anne Drabicky all soon followed Ben to the hurricane’s aftermath. They were moving in new and unknown territory, on their own, flexing their wings.

I started to receive cell phone calls from them as they began discussing procedures and what to look out for at the site of the hurricane. They asked good and specific questions, and I provided them with balanced, but nonetheless worst-case scenarios; it would have been senseless not to warn them of the dangers. But I also gave them broad instructions, since it was impossible to imagine all they were going to see and encounter:

- I spoke to them of desperate, hungry, burnt-by-the-sun, dehydrated and pissed-off people waiting in vain for help from federal officials and who might not be in the mood for the arrival of a bunch of white college kids with their expensive digital cameras. It was likely not going to mean much to these people that these young visitors were innocent and well-meaning.

- I suggested making eye contact, letting their possible subjects know that they were dealing with a genuine person. I let them know how people can connect with each other through a look that passes one to the other. The look could say “Go away,” or it could say “Look at me. I want someone to know what is happening here.”

- I told them that they might be entering dark places, in both a physical and spiritual sense—a place of people in a world of hurt. I warned them that there would be predators afoot and to look out for each other.

- I assured them that no photograph was worth dying for, and that I didn’t want to fill out a lot of papers and have to explain to their parents why they were no longer on this earth. Besides, someone else would then have to edit their photographs, and I knew they wouldn’t be happy about that, which was my way of keeping it light and yet scaring them into paying attention. If they were going to go, with or without permission, then they needed to go with their eyes wide open.

I couldn’t sleep, probably because I knew that closing my eyes was not an option until all of my students were safely back home in Austin. The days turned into a swirling cloud of class work, lectures and dealing with the confusing images that came from the hurricane sites. These photographs portrayed actions that made me feel uncomfortable about what human beings are capable of doing to one another, but other images left me with feelings that made me glad to be a part of the human race.

In time, my students all returned to Austin. Their spirit was indomitable, and as we talked about their experiences I could tell that they’d approached the victims of the flooding in a manner sensitive to their plight. They’d also drawn many lessons from their experiences. Mark told me he’d learned more in the two days he photographed the hurricane’s aftermath than in his previous two years in college.

It was my good fortune to have worked with these students as they made coverage of this hurricane their first leap into the void. But I found this experience difficult because I, too, wanted to cover Katrina, yet I had to honor my teaching commitment at the university. However, these students honored the teaching of their professors by making some extraordinary photographs under very difficult conditions. Because of the strength of their coverage, I was able to connect some of them with a weekly national magazine. In a rare and special circumstance, Ben had some of his work selected by Magnum Photos to appear on their Web site. Magnum President Thomas Hoepker commented that he found a number of Ben’s images to be gripping.

The students are continuing their work knowing that this experience marks only the beginning of their journey as photojournalists. They are passionate and committed to making a difference in this world. They have varied approaches to their work, but they are speaking with their hearts and their brains, and I applaud them.

Eli Reed, a 1983 Nieman Fellow, is a photojournalist and professor at the University of Texas at Austin. An article based on the Hurricane Katrina experiences Reed describes on this page appeared on the digitaljournalist.org Web site. Also on that site are essays from Reed’s University of Texas students about their experiences covering the hurricane and some of their photographs in the form of a multimedia presentation.

“Han Nguyen stands atop the remains of a Vietnamese grocery store where he took shelter on August 29th when Hurricane Katrina struck Bay St. Louis, Mississippi. After waves had obliterated the building, Nguyen survived by holding onto a tree for 11 hours.” Photo by Sloan Breeden.

“High above the flooded neighborhoods of New Orleans on September 5th, a member of the National Guard surveys the damage left by Hurricane Katrina when levees broke a week earlier.” Photo by Sloan Breeden.

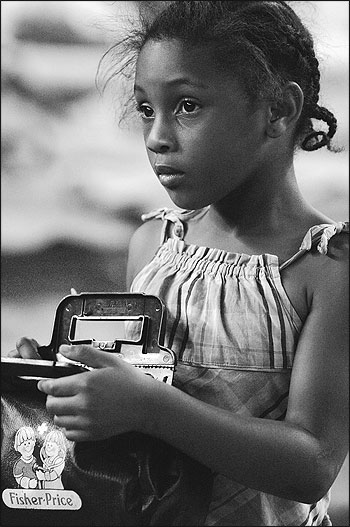

“A young girl stares at the scene at the Astrodome in Houston. I have several shots of this girl with the same faraway look on her face, where she seemed sort of frozen for a few moments.” Photo by Anne Drabicky.

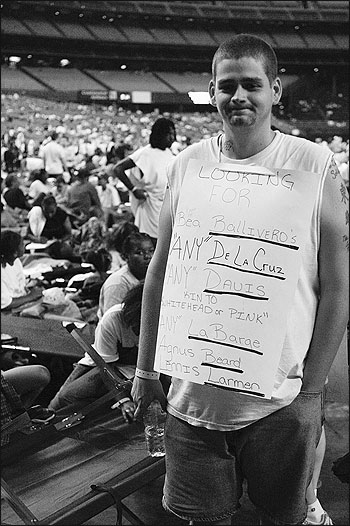

“A man looks for relatives and helps other people look for theirs as well at the Houston Astrodome as he walks slowly between the many rows of cots.” Photo by Anne Drabicky.

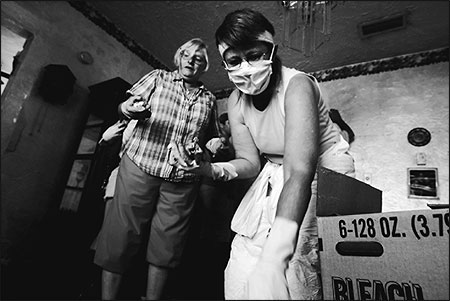

“Sharon Beasley helps her friend Katrina Blackwood wrap the remaining valuables left in her home in Gulfport, Mississippi. Bleach and other sanitizers were passed out by local volunteers to help residents clean their homes.” Photo by Meg Loucks.

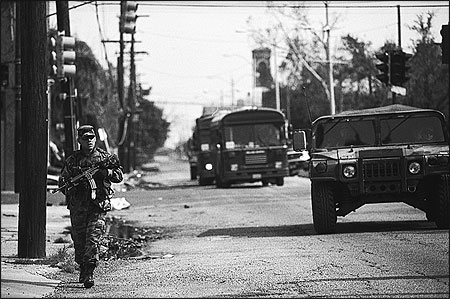

“Members of the National Guard patrol New Orleans’ French Quarter on Labor Day, one week after Hurricane Katrina struck the Gulf Coast.” Photo by Mark Mulligan.

“A woman passes through a local church in Bay St. Louis, Mississippi after Hurricane Katrina whipped through their town. The church had been recently renovated and, although the interior was damaged, the stained glass windows survived the storm.” Photo by Meg Loucks.

“A statue in the Bay Catholic Elementary School in Bay St. Louis suffered three feet of flooding in Hurricane Katrina. September 10th.” Photo by Rob Strong.

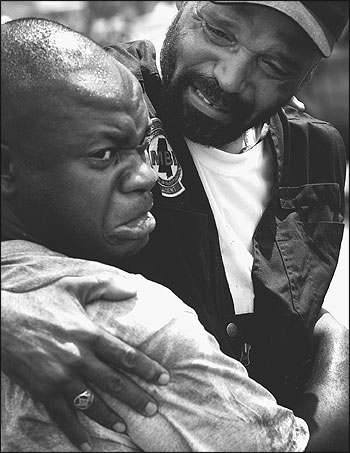

“In a brief moment of joy, Troy Lee, left, embraces his friend Joel Wallace when they discovered each other at the Bay High School shelter two days after Hurricane Katrina, in Waveland, Mississippi.” Photo by Benjamin Sklar.

“As Hurricane Katrina rages, emergency volunteer crews attempt to rescue the Taylor family from the roof of their car. Floodwaters overpowered and trapped the car on U.S. Highway 90 during the storm on August 29, 2005, in Bay St. Louis, Mississippi. All six members of the family were safely rescued.” Photo by Benjamin Sklar.