Time in photography isn’t only about its passage, whether measured in hours, days or months. It’s about its captured moments, be it in a second, or five hundredths of a second.

Increments of time are imperceptible to the eye, but not to light sensitive film. The difference between a fifteenth of a second and a hundred and twenty-fifth of a second alters the way in which what stands before the camera is depicted. A blending happens at slower shutter speeds. What can be seen as sharply defined objects turn to mood and atmosphere that could have come from an artist’s brushstroke.

Shutter speed is just one technique photographers use to take visual information to a level beyond what, on its surface, it represents. To the viewer, the photographic image can invoke feelings, trigger thoughts, and project perceptions to be pondered. And when it does, a photograph achieves what imagery has always endeavored to do—it stirs emotion and leaves an indelible impression.

In photography, these captured moments aren’t the only vehicles in which time works to bring about feeling. The days, weeks, months and years devoted to gathering visual information on a particular subject also contribute. It is this passage of time combined with the moments seen through the camera’s eye that costitute a document known as a photo essay. It is in such documents that much of our recent visual history has been told. And it is these documents that are at the core of what began as photo-reportage.

Today, photojournalism is different from what it once was. Speed is what counts. Instantaneous reports about world events, stock markets, even sports have become the norm. And news photography keeps pace. But has speed changed the content quality of what we see and, for that matter, how life is portrayed? To these questions, I answer yes.

There is a division in photo reportage. There is photojournalism and there are photo documentaries: Identical mediums, but conveying very different messages. Documentary photographers reveal the infinite number of situations, actions and results over a period of time. In short, they reveal life. Life isn’t a moment. It isn’t a single situation, since one situation is followed by another and another. Which one is life?

Photojournalism—in its instant shot and transmission—doesn’t show “life.” It neither has the time to understand it nor the space to display its complexity. The pictures we see in our newspapers show frozen instants taken out of context and put on a stage of the media’s making, then sold as truth. But if the Molotov cocktail-throwing Palestinian is shot in the next instant, how is that told? And what does that make him—a nationalist or terrorist? From the photojournalist, we’ll never know since time is of the essence, and a deadline always looms. Viewers can be left with a biased view, abandoned to make up their minds based on incomplete evidence.

Through documentary work, the photographer has a chance to show the interwoven layers of life, the facets of daily existence, and the unfettered emotions of the people who come under the camera’s gaze. When finally presented, viewers are encouraged to use their intelligence and personal experiences, even their skepticism, to judge. By eliciting associations and metaphors in the viewer, an image has the potential to stimulate all senses. But photographs that do not fulfill this potential remain visual data whose meaning is limited to the boundaries of the frame; the viewer is left to look, comprehend the information presented, and move on.

There are photographers who create exhibitions and books from their photojournalistic images, but what is achieved is only sensationalism. One extreme moment after another is cobbled together and made to look as though it captures “life.” Having traveled to many of the world’s disaster areas and having seen extreme tragedy, I can attest that these moments do happen. But around them there is more to see and more that must be understood. There is more than the angry mob: There is the “why” and the “how” behind their actions. There is more than the flood of refugees: There is what they leave behind. There is more than the funeral of a martyr: There is the space they leave empty in their family’s life.

Because of time constraints the pho-tojournalist doesn’t often capture these more subtle but essential images. The documentary photographer does. Photojournalists look to add meaning or message to their pictures by employing contrasts and juxtaposition. In actuality, these are time and space savers. Juxtaposition implies an intersection where extremes or opposites meet. Contrast conjures up black and white. But what sits in the between—the gray, the similar, the normal? Documentary photography offers witness to these less obvious aspects of life.

The role of photojournalists is important nonetheless and, as a fellow photographer, I respect what they do under the difficult conditions in which they must produce. But the product they create comes from the need for speed, and this necessity simplifies (and sensationalizes) the images most people see. Should this be the way we process the visual information that we use to inform decisions we make in a democracy?

Separating the documentary photographer from the photojournalist is the reaction each has and the relationship each holds to the images created. One reacts almost instinctually, the other with more studied calculation. The journalist takes what the camera lens captures, while the documentary photographer makes the images as a form of storytelling, seeking to elevate understanding about what the camera’s eye is recording. Given these distinctions in visual portrayal we, as viewers, need to be wary of the solo image and treat it in the way we do other bits of random information. Without a broader context, skepticism must be exercised as the sensationalistic photograph is handled similarly to unfounded words.

Documentary photographers walk in the wake of this instantaneous parade of visual information. They gather and create images that can look soft, speak loud, and transform the split second into an everlasting glimpse at the truth.

Antonin Kratochvil, a freelance photographer based in New York City, is with the VII photo agency. In nearly three decades of work, he has won many distinguished awards, including the Infinity Award from the International Center of Photography. His books include “Broken Dreams: Twenty Years of War in Eastern Europe,” “Mercy: From the Exhibition,” and a new book of portraits, “Antonin Kratochvil: Incognito.”

Michael Persson has worked for many of the world’s news photography agencies in areas including the Persion Gulf, Soviet Union, Eastern Europe, Africa and Yugoslavia.

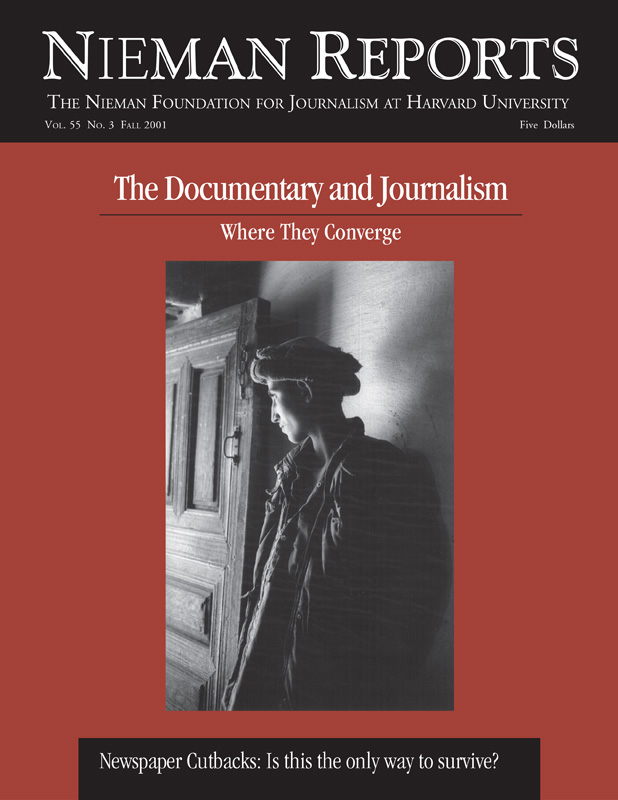

Mongolia, 1996.

This is one of the saddest of the many pictures in my collection. Captured street children in Ulan Bator, Mongolia’s capital, are hosed down before being put into a youth detention center. A tiny child cowers against a cold wall, awaiting his violent shower. Cropping within the viewfinder helps to show how small and frail the boy is in relation to his environment. He is the main subject. But to the side, in a watery light, another boy looks into the lens, judging me or you and seeming to ask if we have the right or the guts to stare. He is ghostly, making his presence all the more ethereal.

In a way, with this photograph I capture myself becoming the event I thought I was documenting. I am being assessed, and I am not afraid to show as much. So often, the press can become the event. Sweeping in, they drain a situation of its drama, unaware that their subjects are reacting to them and not their plight. Their subjects become simply figures to be photographed, filmed, quoted and forgotten as the press move to their next revelation.

It is doubtful that photojournalists would have taken this larger picture because the cowering figure is what matters to those who deal in shock value. But respect for people, respect for their lives, is as important as a reporter’s duty to cover their stories. As I spent time with these children, they grew comfortable with me, perhaps to the point of trust. This shot was my way of giving them a voice that dares the viewer to enter their desperate world.

Romania, 1995.

The Gazeris are the oil scavengers of Romania’s crumbling infrastructure. Working the contaminated land, they salvage seeping, secondhand oil in order to survive. This story isn’t shocking enough for photojournalists to cover. Why? No one is dying or dead, and no one is ablaze with oil. Where’s the news? Yet what I found in these images is an excellent illustration of how humanity prevails in whatever pathetic capacity, in whatever terrible conditions, exist.

This picture comes together through the use of metaphoric symbols. There are no juxtapositions, no contrasts, just unrelated moments that come together to make a whole. The dilapidated, arcane trolley with a funnel tipping out from a solitary barrel seems to me to represent futility at rest. The two people walking in opposite and disconnected directions. The indistinguishable liquid on the land—is it water or oil? The way the woman in the foreground bows her head and folds her arms. This isn’t the body language of someone who is happy.

Finally, there is the hole from which comes what allows the Gazeris to survive. Or the hole might represent a pit into which life’s interminable crap is to be unloaded. In Czech we have a saying, “Je to v pytly.” It’s all in the bag. It means, what does it matter, it’s all for naught. These observations and associations come to me when I shoot because I have time to think about what it is I’m doing and not simply react to what’s in front of me. On the surface, this picture seems nothing much until you dig deeper and then, your prize. This is not dissimilar from the Gazeris and their labors.

Rwanda, 1994.

The bodies lie all about, two deep. Left in a church where their putrid smell was enough to make me feel I’d just passed through the gates of hell. I walked among them instead of shooting the rotting pile of flesh through the window. I chose to meet the image head on, not skid around the carnage. The body in the foreground confirms what the viewer fears. Yes, these are dead people. The image is shot in low light, giving the image a slight blur as if what’s on view had been painted by Brueghel. This image would have been considered too abstract and technically unacceptable for photojournalism. But to the living, death remains surreal in spite of all we know. As I walked through the bodies, I apologized each time I accidentally stepped on an arm or a leg. Who was listening? I don’t know, but perhaps this was a way for me to retain my sanity.

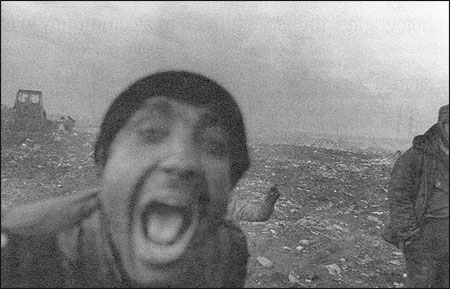

Goma, Rwanda, 1994.

This shows the half-masked identity of one of the “Interahamwe,” the death squads who carried out the mass slaughter of Rwanda’s Tutsis during the country’s genocide. Cropping allows for the concealment of identity and subtlety of message. Killers do not walk with signs saying “killer” on them. They look like you and me. It is what they do that makes them what they are. So their appearance inspires the mind to conjure thoughts of what it is they do and how. By hiding some of the information and allowing the mind to fill in the rest, the picture lays the foundation for deeper thought. In this image, the unidentified people in its hazy background help this process by raising the question about whether they are killers or survivors. There are no dead bodies, so it is even a more complicated question. We are left with an eerie feeling of concealment, bordering on the clandestine. In photojournalism, identity is everything: Faces must be distinguishable so viewers are able to relate to the subject.

But how can someone sitting in New York with a job and modern life have any affinity with a wounded or dying man from a place and culture so far removed from their own, or with a murderer of hundreds of countrymen? A galaxy of dissimilarity separates subject from viewer, and there can be no connecting across this chasm. By not forcing this connection, documentary photographers keep their differences intact while giving viewers the chance to feel and imagine on their own levels, engendering a response—no matter how vague. The main thing is that viewers aren’t bullied or coerced into an emotion that they wouldn’t naturally have. Perhaps the space in the shot is the distance between the killer and his victims, or the separation from the group, distinguishing him from the rest by his actions. These are all questions, not answers. Questions, however, do stir.

Afghanistan, 1988.

This shot is a prime example of using slower shutter speeds to create images that go beyond what they are. I call this my “Pieta.” Brush strokes of light transform this mother carrying her dying child into a picture bearing an array of religious undertones. This is in no way belittling the fact of what is really happening. A mother with a dying child is one of the most desperate situations a human can face. Why, then, transform it into something that lessens this tragedy? To my way of thinking, literal images begin and end and have no other way of going beyond their literal self. A more abstract image can associate itself with other images or memories and isn’t asking to be taken in as pure information. It is a prompt for the multitudes of links to come to life, thereby leaving a lasting impression through the memories and ideas it inspires.

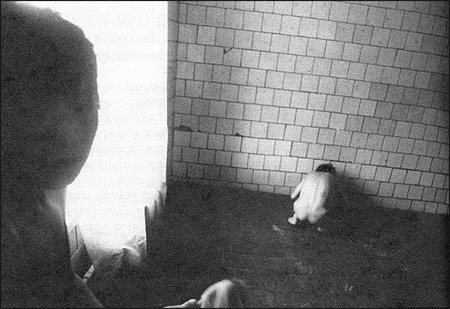

Romania, 1995.

The screaming man in this shot reminds me of Edvard Munch’s “The Scream.” When I work, I see much of what I do as a personal journey, and the images I make are a reflection of my experiences and endeavors. Being a married man and a father, having seen my parents pass away, and thinking about my own death give me feelings of what it is to be alive. The older I become, the more I understand, and my photography reveals this changing comprehension of mortality. Many young photographers hit or miss with their documentary photography. When they hit, it might be a feeling they’ve stumbled on or a technique they’ve inadvertently mastered. But missing means life has yet to reveal its gifts.

In this photograph, “life” appeared while I was busying myself with the shot behind the screaming man. In fact, when this reaction exploded, my subject’s arm seemed to grow out from the head as I pressed the shutter. This image speaks of how things in front of the lens can also react with the lens. It is a two-way street. As much as you look at them, they look back at you. One’s personal journey of life is woven into documenting this particular moment.

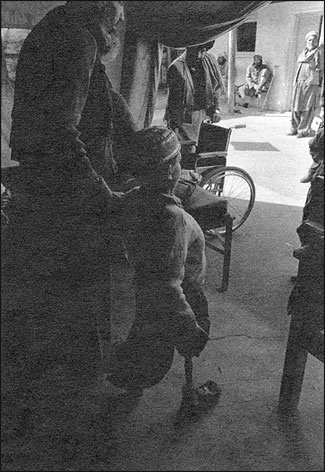

Afghanistan, 1988.

The little boy with the prosthesis may be a victim, but this photograph is not a “victim shot.” Ravages of war are apparent, yet it is hope that jumps out of this image. It shows the various obstacles life presents—the boy’s missing leg—and that with a little help from his grandfather who guides him, people can emerge from despair and walk in the light once again. It is optimism I show here, the healing process after injuries have been suffered and sustained. The boy’s face is barely discernible. His identity is unimportant. There are perhaps thousands of boys like him with similar fates in Cambodia, Angola, Mozambique, not to mention his own country. It is a picture that speaks of something that will happen, not that has happened. Photojournalism concerns itself with results, not intentions. Intentions don’t make for drama. Actions and their consequences do. This generic symbol speaks to all of us about the courage we find in the midst of adversity. It speaks to us of the human condition.

All Photos by Antonin Kratochvil ©