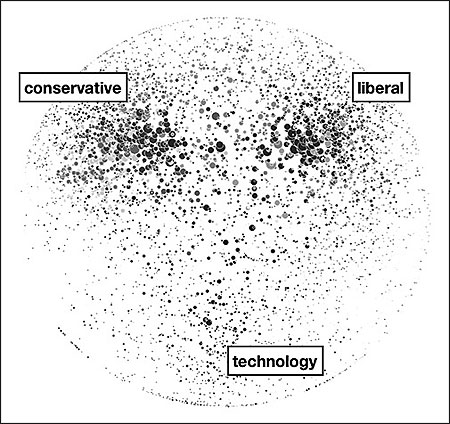

This social network diagram of the English language blogosphere shows major clusters around politics and technology.

Mapping the patterns of how people share information in the blogosphere makes visible and understandable what otherwise can seem unruly and complex. Using social network analysis and advanced statistical techniques, we can analyze the exchanges in cyberspace to create maps of community and attention among many thousands of bloggers. Mapping these online networks tells us a lot about how community is formed around kinds of information that bloggers seek and share with one another. And these findings provide clues that can give journalists a clearer sense of how what they do will be utilized in the age of digital media.

What our mapping analyses have shown us is how the emergent clusters of similarly interested bloggers shape the flow of information by focusing the attention of thematically related authors, and their readers, on particular sources of information. These social networks include new actors alongside old ones, knit together by hyperlinked multimedia into a common fabric of public discourse. Of great interest—and perhaps surprising news—to journalists is our finding that legacy media, journalistic institutions in particular, are star players in this environment.

While blogs are promiscuously available representations of what a person or organization would like the world to know, in practice the world at large is not likely to care about the content of any given blog. However, a community of specifically interested others will often arise around a blog in ways similar to real-life social configurations with which we are quite familiar. As the number of blogs increases exponentially, this “citizen generated” network is quickly becoming the Internet’s most important connective tissue. In fact, the combination of text and hyperlinks (and, increasingly, hypermedia) makes the blogosphere arguably as much like a single extended text as it acts like an online newsstand.

To the extent that readers’ patterns of browsing tend to follow the direction of links available in this hypertext network, the structure of the blogosphere suggests a kind of “flow map” of how the Internet channels attention to online resources. And this is what we are able to map—the extraordinary number of blogs authored by emergent collectives: public, persistent, universally interlinked, yet locally clustered and representative of myriad social actors at all levels of scale.

Peering Within the Patterns

What we find is not “media,” in the familiar sense of packets of “content” consumed by “audiences,” but a new form of communication. We write. We link. We know. In this networked public sphere, online clusters form around issues of shared concern, information is collected and collated, dots are connected, attitudes are discussed and revised, local expertise is recognized, and in general a network of “social knowing” is knit together, comprised of both people and the hyperlinked texts they co-create.

As David Weinberger observed in his 2007 book, “Everything is Miscellaneous: The Power of the New Digital Disorder,” “as people communicate online, that conversation becomes part of a lively, significant, public digital knowledge—rather than chatting for one moment with a small group of friends or colleagues, every person potentially has access to a global audience. Taken together, that conversation also creates a mode of knowing we’ve never had before …. Now we can see for ourselves that knowledge isn’t in our heads: It is between us.”

The links represent the conscious choices of bloggers and fall into two main categories: static and dynamic. Static links are those that do not change very often and are typically found in the “blogroll,” a set of links a blogger chooses to place in a sidebar. Blogroll links are created for different reasons, but the network formed by them is relatively stable and represents a collective picture of every blogger’s perceptions of the blogosphere and his or her own position within it. Dynamic links change frequently and typically represent links embedded in blog posts, a hard measure of a blogger’s attention.

When the interests of many bloggers intersect, something we call “attentive clusters” typically form: groups of densely connected bloggers who share common interests and preferred sources of information. We analyze the behavior of these clusters to discover how the community drives traffic to particular online resources. By doing so, we can provide an important key to understanding the online information ecosystem. And here is some of what we’ve learned:

- The blogosphere channels the most attention to things besides blogs. Of the top 10,000 outlinks, only 40.5 percent are blogs, and these account for only 28.5 percent of dynamic links.

- The Web sites of legacy media firms are the strongest performers. The top 10 mainstream media sites, led by nytimes.com, washingtonpost.com, and BBC.com, account for 10.9 percent of all dynamic links.

- By contrast, the top 10 blogs account for only 3.2 percent of dynamic outlinks.

- Though the top 10 Web-native sites (blogs, Web 2.0, and online-only news and information sites combined) account for 10.8 percent of dynamic links, two-thirds of these (7.2 percent of total) are due to Wikipedia and YouTube alone.

Legacy media institutions are clearly champion players in the blogosphere. Given that online-only sites are the most skewed—in terms of political leanings, advocacy positions, and tone of information—of all forms of news and information Web sites, what we find is that legacy media holds the center, while online-only media are frayed at the edges.

Future Direction

Are blogs and Web-native media making old-style institutional journalism obsolete? Of course, this question has several dimensions. At the commercial level, institutional journalism is threatened by the Internet, both in the form of “citizen media” taking its advertising-earning eyeballs and online classifieds taking its rent on informal markets. At the tonal level, the integrity and validity of “objective” journalism and responsible expert opinion is contrasted to the more slippery and uncertified forms of online content found in blogs, YouTube, and other user-generated content.

In discussions about their varying practices, journalists and bloggers argue over values of professionalism, independence, legal protection, and legitimacy as vessels of the public trust. But the picture is more complicated. Most links from blogs are not to other blogs but to a range of online sites among which mainstream media (MSM) outlets are the most prominent. And journalists are keenly attentive to blogs, often mining them for story leads and background research. Furthermore, the blogosphere is becoming as important as the front page of the paper for landing eyeballs on a journalist’s story. There is a cycle of attention between blogs and the MSM, in which the MSM uses the blogosphere as a type of grist for the mill, and the blogosphere channels attention back to the MSM.

What is becoming clear is how the blogosphere and MSM are complementary players in an emerging system of public communications.

Yochai Benkler, the author of “The Wealth of Networks: How Social Production Transforms Markets and Freedom,” proposes a model in which the “networked public sphere,” supplementing the older “hub and spoke” industrial model represented by the mass media, will alter the dynamics of key social communications processes. The mass media model, in which the ability to communicate publicly requires access to vast capital or state authority, has resulted in elite control over the power to frame issues and set the public agenda.

What ends up in the newspaper often starts with a government source or professional media advocate in the employ of one or another interested organization. In Benkler’s view, a new, vastly distributed network of public discourse will supplement or supplant this elite-driven process. The networked public sphere will allow any point of view to be expressed (universal intake), and to the extent it is interesting to others, it will be carried upward (or engaged more widely) via a process of collective filtration. The extended network will contain its specialty subnets (analogous to interest publics) and its general-interest brokers (analogous to the attentive public) among others. This neural network-like system might potentially provide a much more stable and effective foundation for democratic social action than the established commercial media system it challenges.

What we already can observe is how the blogosphere acts as a multifocal lens of collective attention. Interest among bloggers creates network neighborhoods that channel attention to relevant online content. Discovery and analysis of these provides the promise of empirical exploration of new and critical ideas about the dynamics of the networked public sphere.

But what should not be overlooked is the central role that legacy news media entities still play throughout the blogosphere. And if journalists want to continue to fulfill the role they have aspired to in the past—to be general interest intermediaries at the crossroads of public discourse—nothing in the actual behavior of bloggers suggests their role would diminish on account of lack of demand for this social function.

The news media’s business model problems are, of course, another matter entirely, but at this stage it looks safe to say that blogs do not make commercial journalism obsolete, least of all in the eyes of bloggers (regardless of what some of them say about this). If anything, the central role of professional journalism in the expanded economy of political discourse makes it valuable in new ways. To the extent its near-monopoly on agenda setting and public representation is broken, its role as an honest broker of verified information becomes even more important.

Change Is Everywhere

RELATED ARTICLE

“Political Video Barometer”

– John KellyThe growing networked public sphere is not just changing the relationship among actors in the political landscape, but it is changing the kinds of actors found there and changing what “media” are actually doing. Some of this is easy to see. Ten years ago there were almost no bloggers; now, they are considered a formidable force in public affairs. And the legacy media are changing as well. Newspapers and other online publishers have added blogs to their offerings and transformed the way general articles are published to seem more and more bloglike (e.g. hyperlinks, reader comments, embedded video). Bloggers on legacy media Web sites have quickly gained prominence, and some media companies have found great success via blogging. For example, most people outside think of The Politico as a Web site, not a Capitol Hill newspaper.

As blogging and online media genres evolve, blog vs. MSM becomes purely a cultural, or perhaps commercial, distinction and not one of format. If in blogs we find more information about more issues and with more diversity of voices than ever heard in the MSM, why should we mourn the closing of newspapers and the dwindling of broadcast news audiences?

One argument is that the MSM form a locus of collective attention, where citizens are exposed to differing views on a common index of issues, and that the danger of losing this mainstream arena is that individuals will retract into irreconcilable redoubts of the like-minded, and the central marketplace of ideas fade away. There is some evidence to support this fear. In our mapping, we clearly see the strong tendency of bloggers to link to other bloggers with similar interests and beliefs, particularly around politics. And other research buttresses what we can now see on our social networking maps:

- Most people’s offline social networks are relatively homogenous with respect to political beliefs and attitudes.

- To the extent that people are exposed to opposing viewpoints, it is primarily through MSM.

It is, therefore, not unreasonable to fear that the centrifugal force exerted by hundreds of thousands of bloggers will sunder a public sphere long held together by journalistic institutions. But let us also bear in mind that the way we envision this problem reveals just how thoroughly the mass media model of society—featuring atomized consumers feeding at common troughs—grounds our imagination.

I’d argue that the question of how blogs are impacting the public sphere is not a straightforward matter of whether they undermine the MSM’s ability to provide a platform for public agenda-setting and exposure to crosscutting political views. The full story is deeper and more nuanced. While the Internet, vivified by blogs, fractures the landscape of public discourse across a great many new actors, a core activity of bloggers is to focus attention back to the MSM, particularly to institutional journalism. The structured tissue of bloggers—each not a voice in the woods but a member of crosscutting communities—creates a new medium of social knowing, one that so far appears favorable to the presence of the kinds of high visibility, central platforms represented by legacy media institutions.

John Kelly is founder and chief scientist at Morningside Analytics, a company focused on social network analysis of online media, and a research affiliate of the Berkman Center for Internet & Society at Harvard University. This article is adapted from a paper he wrote entitled “Pride of Place: Mainstream Media and the Networked Public Sphere,” forthcoming from the Berkman Center’s Media Re:public project.