This article is written by a journalist in Iran. No byline appears on it due to the situation this journalist confronts while working. This journalist has done reporting for Western television.

To be on the safe side, it is advisable to apply the prefix “semi” in describing events, politics, NGOs and journalism in Iran. “Here is not a democracy, but ‘semi’ democracy,” some write. For others, “It is not a democratic, but a dynamic society.” Sentences like these are used by nearly every Western journalist visiting Iran to describe the society safely while being certain of securing their next press visa and satisfying the curiosity of readers in Europe, Asia and the United States.

But how does it feel to live and work in a “semi” society? It is undecided life, with the risks taken being unpredictable, since its press law is open to interpretation. Punishment for breaking the law depends on many things, too, including who you are and what your job is. For example, a blogger or print journalist committing the same crime might end up with different verdicts. A former classmate in high school writes for roozonline.com, a news wire based in Europe that is moderate in criticism. She is not arrested, though she lives in Tehran. Another person, writing for the same publication, ended up in jail, was bailed out and had to escape Iran.

Reporters, when arrested, can end up in solitary confinement in the notorious Evin Prison. In fact, this is usually where journalists and bloggers are locked up at first for a couple of weeks or months. If they let themselves be co-opted, agree to act as a collaborator after being bailed out, or bid farewell to journalism and go abroad, their cooperation labels them as good or tolerable journalists. They can achieve this by volunteering information about their contacts or those they’ve interviewed, or even tell the interrogators about like-minded friends.

The income “good” journalists can earn is so meager (around $500 a month) that they are forced to compromise their professionalism by being an advertising agent or by wheeling and dealing in planting favorable reporting to business or consumer goods. Many times one of my coworkers at my daily publication wrote letters in Farsi and English to Nestlé or other companies in Iran to negotiate the marketing of products under the excuse of writing “health or food stuff” pieces. Collusion involving moneymaking is also found among sports writers. The sports pages have among the highest readership, and dozens of male sportswriters are in jail because they’ve been involved in fixing matches or, in most of these cases, served as brokers in selling and buying soccer and basketball players.

Self-censorship: To write in Farsi is to push internalized red lines from the subconscious to conscious. Those well versed in the ways of self-censorship transgress these red areas unknowingly in the same way a soldier finds his way through a minefield. A well-experienced journalist is defined in this instance as “a person who can say what he means in a way that the friends (audience) can get the point and the enemies (censors and pressure groups) miss the point.” Another effective form of self-censorship involves distracting the focus of the audience (including writers at the dailies) to the disastrous woes of the current economic crisis in the United States, in particular, and the West, in general.

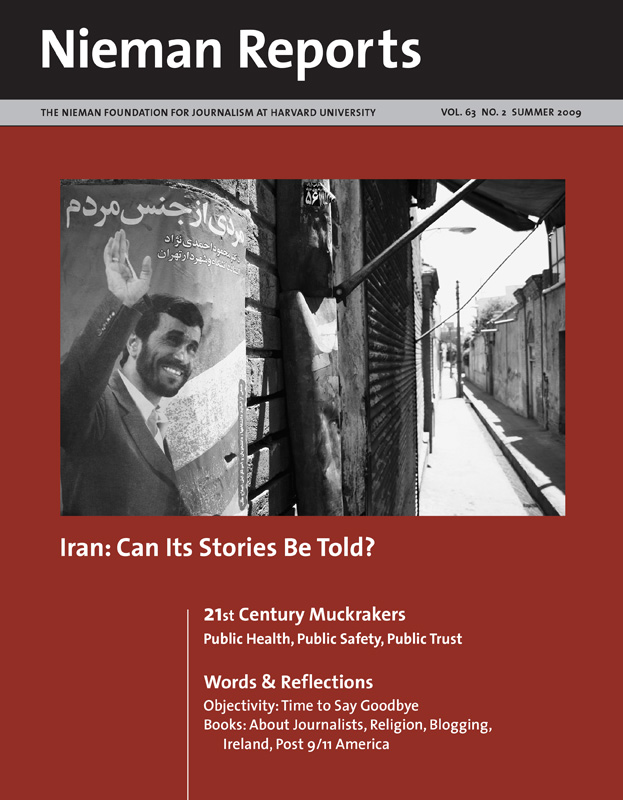

Heaping invectives on the U.S. administration and its misconduct can also be a way of continuing to work as a journalist while staying out of jail. Another tricky way to do this is to take advantage of the dichotomy of so-called reformist and conservative camps by acting as a journalist with impartiality. In short, whatever is written should prove that you are a strong believer in the ruling establishment and you see eye to eye with the supreme leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei. When you are seen as a sympathizer to the regime, you can criticize the incumbent government. Translating Western newspaper articles can be used as a safety valve to say what you mean through other stories, for example about Turk or Arab societies or regimes.

EDITOR’S NOTE:

The “yellow press” is a popular name for newspapers and periodicals of the early 20th century that published news stories of a vulgarly sensational nature, a name synonymous with gutter press.Postal costs and subsidized dailies: The cost of publishing nearly all of Iran’s daily newspapers is subsidized by low interest loans. With monthly or weekly magazines (with the exception of the “yellow” press) subscribers are diminishing in number as people lose interest in reading what they consider to be old and outdated articles and analysis, since many of these publications contain no firsthand reports. And postal costs have recently been almost tripled, which has only worsened this situation—a monthly magazine that costs less than one dollar now costs almost three dollars to be mailed. As one well versed journalist said, this additional cost has been the “finisher bullet” to any independent periodicals.

Lack of newspaper readership: Historically, with its low readership and circulation of dailies, Iranians do not rely on newspapers to get information. In fact, daily reporting of news about human events is not what the average citizen seeks. The Hamshahri (Citizen), the city of Tehran’s mouthpiece with the highest circulation of around half a million a day, is not sold for its news content but for its advertisements, real estate vacancies, and eulogies of the dead. Voice of America (VOA) and more recently BBC Persian (on radio and TV) and the Internet through proxies are the main sources for news for urban residents. To understand how small the impact of newspapers is, I remind you that for more than two weeks during the New Year holidays, which started on March 21st, no newspapers were published, and their absence was not felt at all.

RELATED ARTICLES

“Attempting to Silence Iran’s ‘Weblogistan’”

– Mohamed Abdel Dayem

“Blogging in Iran”

“Publishing and Mapping Iran’s Weblogistan”

– Melissa Ludtke

“The Virtual Iran Beat”

– Kelly Golnoush NiknejadMovement toward the Internet: Censorship, low payment, and the high risk of arrest for any journalist who dares to take an investigative step, among other reasons such as lack of individual liberty, have pushed Iranian journalists to the virtual world of the Internet. This is happening even though the adviser to Tehran’s general prosecutor has said that Iranian officials blocked about five million Web sites in 2008. This has forced some of these digital journalists to look for jobs at Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty (Radio Farda), VOA and BBC Persian, or simply seek a nonjournalistic or public relations job to promote goods rather than act as the conscience of public opinion. Some create their own independent press, if it is possible to do so.

EDITOR’S NOTE:

Read more about Omidreza Mirsayafi’s death »I used to see many of my journalism colleagues at Café Godot (named after Becket’s play) near the University of Tehran; now I read their bylines or hear their voices in Radio Farda, BBC Persian, or VOA. Those who are like me—a young journalist who remains in Iran—have to write as a sycophantic journalist, finding some way to castigate the United States and Western society, in general, while at the same time saying something between the lines. This is not journalism, rather it is compromising one’s principles day in and day out. However, when journalists dare to write under pseudonyms for any Persian news wires outside of Iran, they will face a harsh punishment, such as happened with Sohail Asefi, who escaped, Nader Karimi, who is still in jail, Omidreza Mirsayafi, who died in jail, and dozens of others who still are kept in Evin Prison.