“The border was mysterious, lawless and magical. It was the frontier where cultures collide and blend. And the global future in the making,” writes Sebastian Rotella, as he recalled his reporting from the U.S.-Mexico border during the 1990’s. Still with the Los Angeles Times, now as Paris bureau chief, Rotella remains “obsessed with borders” and writes about how he probes the consequences of immigration in Europe. “What’s going on in Europe today is, literally and figuratively, a border story,” whether the border is on Paris’s Avenue Champs Élysées or in the Canary Islands. To create his book, “Migrations,” photographer Sebastião Salgado went to where people were on the move; he found men, women and children fleeing from poverty and hopelessness and also refugees escaping from enemies determined to destroy them. “… they allowed themselves to be photographed,” Salgado writes, “because they wanted their plight to be made known.” A selection of photographs from his book appears with words about how bearing witness to these migrations changed him.

Phillip W.D. Martin, an independent radio producer, describes an upcoming six-part public radio series entitled “Standing Up to Racism” that is focused on individuals and groups that “are standing up to the intensifying hate in Europe.” This is a story Martin found not being widely reported despite “this major societal and political shift taking place.” From the Netherlands, journalists Yvonne van der Heijden and Evert Mathies tell the story of how — in response to a political assassination and internal discussions — reporters have altered their coverage of the nation’s large migrant population. From a time when the media ignored migrants, just as migrants ignored the Dutch media, now “the lives of migrants and their communities” receive a lot more press attention. Mary Kay Magistad, Northeast Asia correspondent for “The World,” explores the emerging “new attitude toward migrant workers” in the Chinese news media as they report on “the biggest and fastest rural to urban migration in human history.” Not long ago regarded as “a necessary, if somewhat grubby, embarrassment to the more sophisticated urban citizenry,” now topics such as worker exploitation, harsh treatment by authorities, and worker protests are covered, but within the regulations of the country’s state-run media.

Raised in Los Angeles by Guatemalan immigrants, Héctor Tobar, Los Angeles Times Mexico City bureau chief, describes “the segregation” between journalists and immigrant communities and explains why this happens. “The Times’ coverage of immigrant communities is like that of most other papers,” he writes. “It focuses on cultural conflict, on the ‘otherness’ of the people who live there.” In South Central Los Angeles, where Latino immigrants are displacing African Americans, photojournalist Lester Sloan believes that press coverage inflames tensions; “Journalists owe the community of South Central more than infrequent scrutiny during periods of chaos,” he writes. Photographer Donna DeCesare peers inside the troubled lives of immigrant youths who turn to gang membership in the United States, then are deported and bring gang affiliations and activities to Central America. Rarely does she find other journalists following this story on what she calls her “lonely trail.”

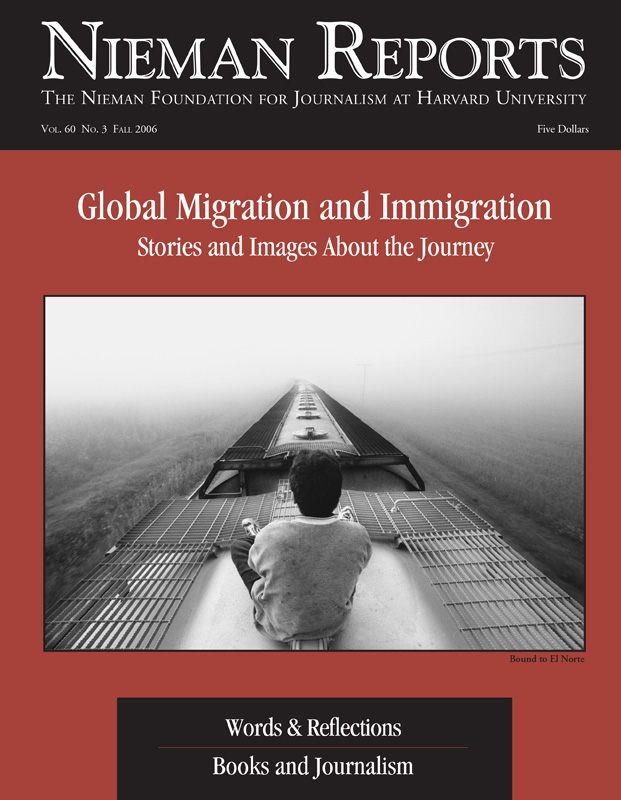

To tell the harrowing journey of Enrique, a Central American boy determined to reunite with his mother living in the United States, Los Angeles Times reporter Sonia Nazario confronted ethical and logistical reporting issues. She talked about them in a journalists’ forum, including research she did on “what were the legal lines, aside from the moral and ethical lines.” Los Angeles Times photographer Don Bartletti provided the images for “Enrique’s Journey” and writes about his work obtaining those photographs, as well as other immigration coverage. “It took me three days, trudging in sweltering heat along five miles of greasy railroad ties, to track down this legendary act of kindness,” he writes of one image. To find out how illegal workers obtain necessary documents, Ralph Ortega, a reporter with The (Newark, N.J.) Star-Ledger, acted as “someone here illegally looking to work,” and he describes how his experiences were used to tell the story.

Chicago Tribune reporter Stephen Franklin proposed a project about the feminization of migration when he “could find no articles in any U.S. newspaper that wove the threads of this tale together.” Four Tribune colleagues — Tribune editor Geoff Brown, photographer Heather Stone, Hoy Chicago Editor Alejandro Escalona, and multimedia producer John Owens — join him in writing about the variety of ways in which these stories were presented to print, online and television audiences through a strategy of media convergence.

Reporter Susan Carroll‘s words and Pat Shannahan‘s photographs tell of the deaths of (and sometimes the rescue by U.S. Border Patrol of) illegal immigrants near the Arizona border. Unpopular with readers and difficult to tell, these stories require — and receive — support from editors at The Arizona Republic. Reporter Tom Knudson and photographer Hector Amezcua brought usually unheard voices of migrant laborers to readers of The Sacramento Bee as forest workers told of abuse and exploitation they endured. “We wanted to name names, take pictures, and bring the pineros — the men of the pines — out of the shadows,” Knudson explains. Miami Herald reporter Amy Driscoll observes that her city’s diverse immigrant communities, with their fragmented views about immigration reform, complicate coverage of that issue, and photographer Nuri Vallbona documents the onshore arrival of a Cuban refugee. Boston Globe reporter Kevin Cullen explores what happens when immigrants decide to go home; “Could it be, from a cultural standpoint, like removing a species from an ecosystem, altering it forever?” he asks.

Kate Phillips, political editor of nytimes.com, examines the carefully chosen language that advocates and legislators use to frame the political debate about immigration; she explores how journalists select the words they use in their coverage. “What language is used in stories and headlines — and how it is used — matters,” she writes. Sociologist Amitai Etzioni reveals what he learned about how journalists tend to handle the complex intersection of ethnicity and race in a survey of news coverage about Hispanics. He proposes a new approach to avoid the common problem of “turning an ethnic group into a race.” Stephen K. Doig, a specialist in computer-assisted reporting, and Ted Robbins, a correspondent with NPR, address in separate articles the challenges that data and numbers present to journalists in the coverage of immigration. Doig offers hints about how best to use a computer and other resources to evaluate data, while Robbins describes how reporters often fail to do the research needed to avoid misusing figures put forth by “agenda-driven organizations” or rely too heavily on unverified assumptions. “… it is imperative to investigate how information about these people and the lives they lead in this country is derived,” he says.

Lorie Conway, who is making a documentary film about the Ellis Island immigrant hospital, finds many echoes in newspapers, cartoons and photographs from the turn of the 20th century to “what we see published in newspapers” in the early 21st about immigrants.