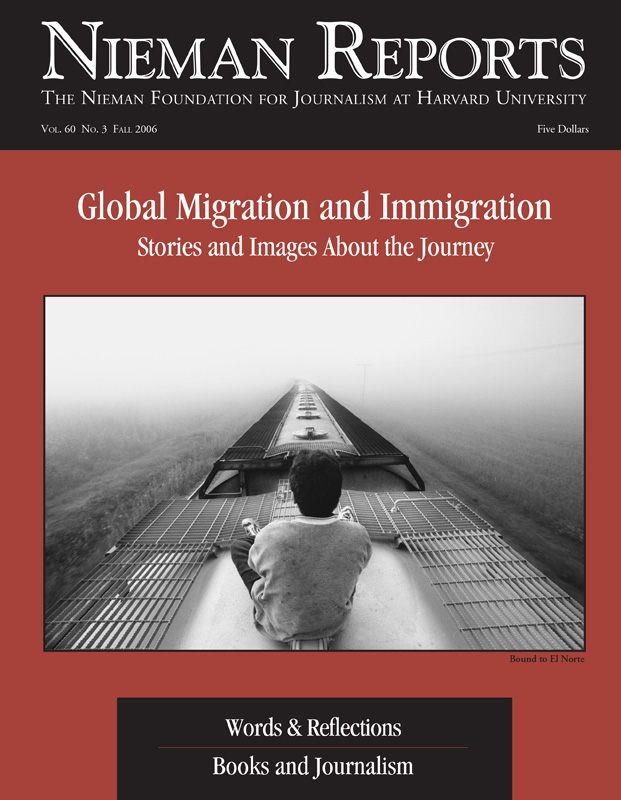

Each year in the vast migration to the United States thousands of migrants, like this Honduran boy, stowaway through Mexico on the tops and sides of freight trains. Some are children in search of their mothers who went before them. At the end of more than 1,500 miles aboard the freights, El Norte comes only to the brave and the lucky.

BOUND TO EL NORTE | TEOTIHUACAN, STATE OF MEXICO, MEXICO | SEPTEMBER 11, 2000

I’d been on this train from Veracruz to Mexico City all night, with it grinding relentlessly through freezing mountain passes and tunnels thick Photos and captions by Don Bartletti/Los Angeles Times.with locomotive diesel smoke. At dawn, most of the riders were huddled down near the wheels in sheltered cavities out of the wind. Climbing a ladder up the side of a car, I emerged topside and was astonished to see the train disappearing into a thick fog bank. Several cars ahead, I spotted the tiny figure of a boy sitting alone. I sprinted closer across three or four hopper cars and made two horizontal and three vertical frames of the boy who never moved or noticed me. The camera clicks were lost in the buffeting winds. I was overwhelmed by his solitude and hesitated to speak to him. Asking his name seemed more a rude intrusion than a journalistic necessity. Then the fog enveloped us. The image and his anonymity are a metaphor: a one-point perspective on an unclear horizon for each migrant who won’t look back.

A stowaway migrant reaches out from a passing boxcar to both accept and thank Fabian Gonzalez (left), 16, for his gift of an orange. Dozens of poor families who live along the tracks in Fortin have made it their mission to toss fruit, tortillas, water and sweaters to stowaways on the trains. Among Central American migrants, the gifts are legendary. Those who survive the constant cruelty and neglect call this “the kindest place in Mexico.”

GIFT FOR A NORTHBOUND MIGRANT | FORTIN, VERACRUZ, MEXICO | AUGUST 30, 2000

It took me three days, trudging in sweltering tropical heat along five miles of greasy railroad ties, to track down this legendary act of kindness. Finally I find a teen named Fabian in front of his family’s rail-side grocery, holding a few old oranges and waiting for the train. The horn sounds. I anticipate the coming scene, set the shutter, and compose the shot: Fabian at the left and a blank space for the train at the right. I’m set as the freight rolls in the frame — but Fabian disappears from my viewfinder! He didn’t throw the oranges from that perfect position next to the store and is now running toward the train. Muttering curses with the camera smashed against my face, I chase after him and stumble over a second set of tracks completely hidden in the weeds. Flailing for balance beside the thundering train, I point my camera in Fabian’s direction and frantically mash the shutter as a boxcar whizzes within a hair of my shoulder. Then the train is gone, Fabian smiles with contentment, his gift delivered. I’m forlorn, sure I missed the moment I’d worked so hard to find and had come so close to capturing.

Three weeks later, with the filmstrip on the light table at the Times office, I see as expected two frames of the blurry boxcar racing by. And the next frame I saw is the picture on this page. My heart exploded with amazement and joy. In perfect focus amid the chaos and motion, the orange passing from one hand to another: a simple exchange and the touch between strangers that means, “Go with God.” The memory, the image, and its message are deeply moving to me — what I find most fulfilling as a documentary photographer.

After 15 hours on the northbound train from the Guatemala border, Honduran laborer Santo Antonio Gamay, 22, cries out from exhaustion and pleads for mercy. Just minutes from leaping off the boxcar, he prays he can outrun Mexican immigration authorities waiting at the approaching checkpoint. He’d been caught twice before.

SPENT | TONALA, CHIAPAS, MEXICO | AUGUST 3, 2000

The roof of the boxcar was sizzling hot, and my backpack squished me like dough on a waffle iron. I was on my belly, peering down over the edge to the space between the cars. Next to me was Dennis Contrarez, a 12-year-old Honduran child traveling alone to San Diego to find his mother. He’d become my friend and sometimes guide on this trip and alerted me that we were slowing down. Two guys below shifted nervously back and forth across the couplers. I squeezed off a few frames as they leaned out looking for signs of La Migra Mexicana. Then Santo Antonio braced his legs over the couplers, fully extended his arms, and gripped the railings. When his head flopped back his anguished expression hit me like a shock. Above the thunder of the train cars and the screeching of the wheels I couldn’t hear if he was crying, yelling or moaning. This unguarded emotion is what I always look for as a photojournalist. It’s what photographers call “a moment,” an unexpected action with lasting storytelling meaning. I barely made two frames before he closed his mouth and opened his eyes. I climbed down, and minutes before he jumped he gave me his name. He confided that he was praying he wouldn’t be deported 200 miles to the Guatemala border on the Mexican Border Patrol’s “bus of tears.”

Having caught the U.S. Border Patrol off-guard, a group of young men leap down the north side of the 10-foot-high steel border fence. For citizens of Latin America who are desperate for jobs, border enforcement and physical barriers are temporary delays in their quest.

TOO HUNGRY TO KNOCK | SAN YSIDRO, CALIFORNIA | JUNE 18, 1992

I like to hang around one venue to observe how a scene develops over a long period of time. Here at the recently fortified fence between the United States and Mexico, I was paying attention to changing light conditions and learning who’s a smuggler or migrant. As I linger to become familiar with a situation, I also become a recognizable presence, easing suspicions that I’m an authority figure bent on surveillance. I like to work close to my subjects with a wide-angle lens. When people get used to seeing my camera and me in the scene they are less likely to alter their behavior just because I’m there. As night falls, the fence is flooded with portable stadium lights. Immigrants laugh that this enforcement tactic is not a deterrent but actually helps them by making it easier to see. Smugglers can recognize when the Border Patrol shift is changing, and that’s when they make their move. At about 1 a.m. someone whistled, and I could hear the clamor as about a dozen guys scrambled their way up the steel fence on the Tijuana side, dropped down the California side, and ran past me to the streets of San Ysidro. I stood still and cranked off five frames of the exact same perspective. Viewed together they look like a sequence from a quick-time movie. This one clearly makes the point.

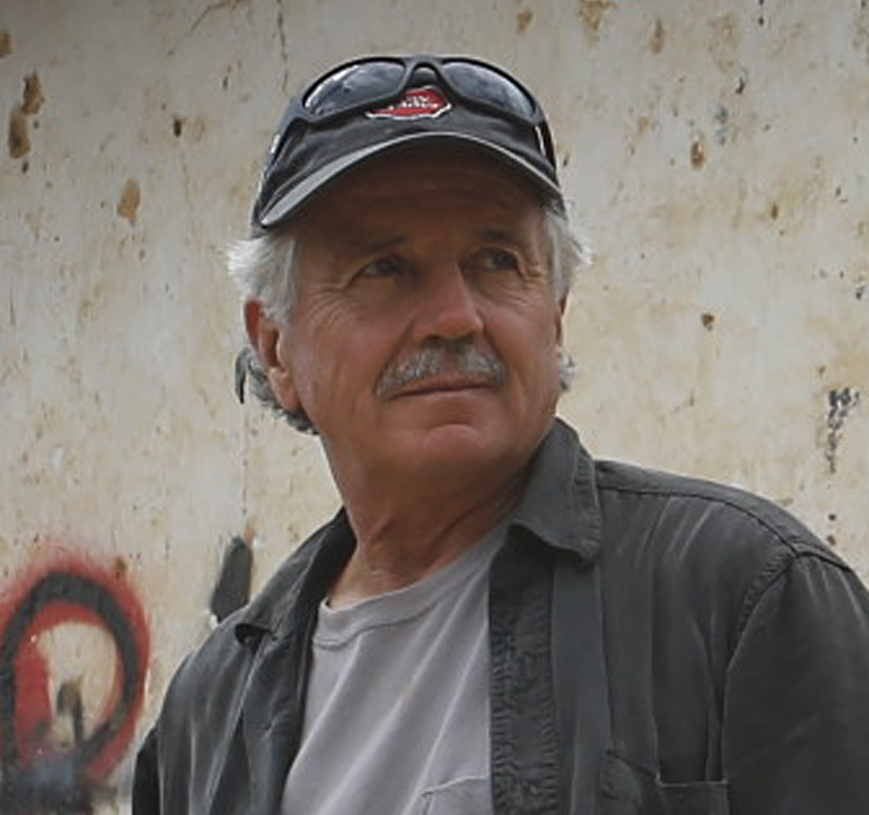

Three brothers and two friends from Guatemala bed down above Interstate 5. Among San Diego’s most recent immigrants, they have chosen this perch to be near the strip mall below where they wait each day for drive-by offers of work.

HIGHWAY CAMP | ENCINITAS, CALIFORNIA | JULY 25, 1989

I knew that migrants sometimes walked from the border, around 60 miles south of this scene, along the route of Interstate 5. Earlier in the day I’d been in ditches beside the freeway looking for signs of migratory paths. While scanning this hillside, a single plastic bag tied to a bush caught my eye. On a hunch, I waited. After nightfall, these five men filed up a path, confirming my intuition that this was a migrant’s camp. Naturally my appearance was cause for surprise and caution and introductions were in order. Conversation was difficult above the roar of traffic, and three of the men were brothers who spoke only the dialect of northern Guatemala. But the other two could understand my Spanish. I assured them I wasn’t working for “La Migra.” I explained that I was from a large American newspaper and for a long time I’d been taking photos of people like them who had traveled from the south to work here. Politely explaining the ethics of journalism, I said I couldn’t help them, but I wouldn’t stand in their way. Even before they arrived I sensed the storytelling potential of the scene. I wanted to show their vulnerability as they slept, their boyish faces in such a risky situation, the intimacy of their personal items — hats, shoes, blankets — contrasted with the streaming traffic of Interstate 5. I stayed with them most of two successive nights until they relaxed in my presence and slipped into slumber.

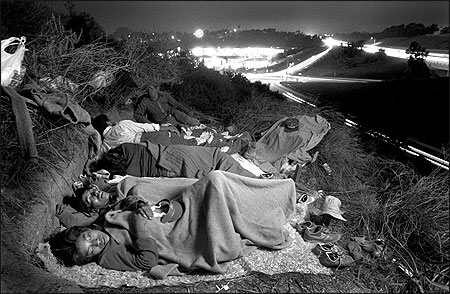

Ten-year-old Gonzalo Lopez’s basketball court is paved with the cold winter mud of the San Luis Rey River bottom. So is the bedroom in his plastic house. Struggling for a toehold in America, his immigrant family is living in a farm worker’s squatter camp. Things are rough. The tomato field next door is too wet to plow. And even Gonzalo’s basketball hoop isn’t working right, forcing him to dislodge every free throw with a branch.

GONZALO’S BACKYARD | OCEANSIDE, CALIFORNIA | MARCH 16, 1991

Gonzalo’s family accompanied his father to the fields of this rich agricultural valley in the prosperous suburbs of North San Diego County. I’d initially visited the camp with an outreach group from a local community clinic. Since I live about five miles away it became my custom to stop by several times a week on my own. I was especially interested in the recent arrival of women and children to what had previously been a subculture of male farm workers. Now families were trying to eke out an existence during the worst of the California rainy season. No clean water, power or sanitation. But the sight of this little boy’s creation stopped me in my tracks. A child’s natural inclination to play is a delightful new addition to the harsh life in a migrant camp.

Just hours ago, Wilfredo Ramirez took the oath of American citizenship. He poses with his certificate on a beach where the border fence between Mexico and the United States ends in the Pacific Ocean. It was 17 years ago when he crossed illegally into the United States near here. Back then he found work picking tomatoes and earned just enough to support his family in Oaxaca. Today he is foreman with a northern San Diego County roofing company and speaks fluent English. As a naturalized citizen, he dreams of legally bringing his wife and children to live with him in California.

BORDERLINE CITIZEN | IMPERIAL BEACH, CALIFORNIA | MARCH 28, 2006

I met Wilfredo 17 years before we made this portrait. In 1989 he’d just arrived in Carlsbad, California and was strumming a corrido on a crummy guitar in a squatter’s camp where he lived with his father. As I sat with them outside their brush-covered shacks, I found Wilfredo and his dad to be the most gracious hosts, and they appreciated my attempts to show their struggle. I visited them frequently during the time they worked in the local fields. Over the years, our friendship has shown me the realities of the immigrant experience on both sides of the border. In 1992 I joined Wilfredo in Oaxaca for the annual festival of his pueblo. Many of his fellow villagers would also return home from El Norte at this time. I celebrated with them during the few weeks each year they spend in their home country with their family. I photographed Wilfredo in 2006 when he took his oath of citizenship then waved the tiny flag in celebration with hundreds of other new Americans. As his story continues to unfold, I intend to chronicle his assimilation in his adopted country.

Screaming high school students riding atop a car wave the Mexican flag on the first day of weeks of nationwide marches that coincided with the congressional immigration reform debate. When her attempts to tear the American flag failed, this girl tossed it to the feet of hundreds of schoolmates who paraded behind.

BORDERLINE HYSTERIA | SANTA ANA, CALIFORNIA | MARCH 27, 2006

It’s difficult to cover marches that are in part staged for the media. I ignore people who “ham it up” for the camera. When TV is around, and it was all over this event, people go crazy. I try to shoot around the artificial hysteria. Finally I was out of the media frenzy, walking alone. From a quarter block away, I saw the girl in this scene trying to rip up the American flag. She was so involved in the activity and the flag was so hard to tear that I was able to catch up with her and shoot a few frames before she gave up and tossed the flag to the street.