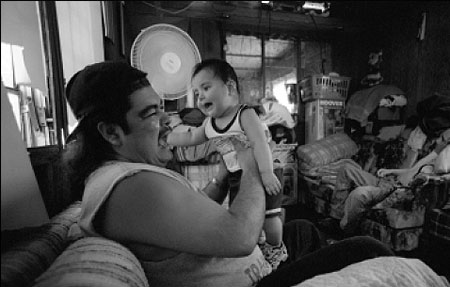

Photo by Denny Simmons.

For years, growth and change came slowly to our pocket of southwest Indiana. The area was influenced by the thrifty Germans who settled here in Evansville, Indiana, and by a Southern way of life, only a short drive across the Ohio River into Henderson, Kentucky. And until recently the word “ethnic” had just one meaning: German festivals staged each summer on our side of the river.

But the booming economy during the 1990’s changed us a lot. The Indiana legislature approved riverboat gambling, and Evansville was awarded the first boat. Then came a new Toyota manufacturing plant just up U.S. 41 and, with it, the arrival of highly educated Japanese families. Soon Japanese was taught in some of our schools. But as these much talked about events transpired, another change was quietly underway. An Hispanic workforce was being attracted to the area by plentiful jobs and a small-town environment; for some, it meant being away from the prying eyes of immigration officials.

At first, a few hundred Hispanic men worked either at an Indiana turkey processing plant or in Kentucky tobacco and vegetable fields. But by the late 1990’s, there were many more Hispanic workers and family members. Still, the number was small, less than two percent of Evansville’s 125,000 residents, compared with a greater presence in major nearby cities such as Nashville, Louisville, and Indianapolis. But in communities like ours, where more than 90 percent of the population is white and English-speaking, their arrival began to draw attention.

Last summer, editors at the Evansville Courier & Press, the largest newspaper (104,000 circulation Sunday, 70,000 daily) in this mostly rural region where Indiana, Illinois and Kentucky meet, decided it was time to explore in depth this small but growing Hispanic community. A highly publicized drive-by shooting of a Mexican immigrant by a Salvadoran prompted this interest, but the editors were curious about the long-term nature of relations between Anglos and Hispanics and also among the diverse Hispanic populations. Of interest, too, was figuring out how Evansville’s experience with Hispanic migration fit into the national picture.

Six months of reporting and writing became a six-day series titled “Hola, Amigos” (Hello, Friends). In March, our coverage spread across news and features sections of the newspaper. We decided to wait to publish our series until the 2000 Census figures were released. Those figures showed that more than 10,000 Hispanics live in our 20-county region, a 150 percent increase since 1990.

“Hola, Amigos” was more of a challenge than previous reporting projects for a variety of reasons, but one stands out. I don’t speak Spanish, and the series’ photographer, Denny Simmons, speaks only a little. (We relied on people we met to help us with translating.) Many Hispanics, especially poorer Mexican adults with relatively little education, spoke no English, so this made some of our reporting difficult. Also, unlike Indianapolis and Nashville, Evansville has neither a Latino Chamber of Commerce nor clearly defined Hispanic neighborhoods, so it was hard to know exactly how and where to begin.

As I set out to report, I didn’t know what to expect. I did know that I wanted to avoid carrying preconceived ideas with me. So, unlike on other assignments, I briefly delayed reading books and searching our newspaper’s library for information about Hispanics. And I waited two months before trying to set up interviews with people at the Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS). I wanted to have a clearer picture of our region’s Hispanic population before I talked with people at the INS.

Although most of the time Denny and I worked separately on the project, we began our journey together by taking an easy one-day trip east on Interstate 64 to Dubois and Spencer counties. Dubois has tidy towns, home-based industry producing furniture components and cabinets, and strong banks. Spencer is where Abraham Lincoln grew up on a homestead. These counties are also where German roots are deepest and where Hispanics first began living when they moved into jobs here a decade ago. In hilltop monasteries and archabbeys, nuns and priests are still being trained.

Dubois’s unemployment rate is so low—at one to two percent—that factory employers recruited Hispanic workers through ads in out-of-town newspapers and by working with an organization that helps Hispanics move out of migrant farm work. Our initial contacts in Dubois included a Mexican store owner and “Padre Gene,” who with other Catholic priests and nuns used his missionary background in South America to quietly reach out to recently arrived Hispanics. Management at the turkey processing plant told us of efforts by local companies to fund an Hispanic Outreach Center.

We worked on the series a day or two at a time, creating a list of leads and names but frequently just stumbling upon people and stories when we left the office. By the time the series ran I’d conducted 80 interviews, more than half with immigrants from Cuba, Mexico, Peru, El Salvador, Colombia and other Latin American countries. Along the way, we befriended people who became our willing interpreters. Every trip or phone interview produced revelations about how schools, hospitals, churches, employers and law enforcement were adapting to language and cultural differences. As we found out, aspects of Latin American culture are seeping into everyday life. At one processing plant, supervisors are learning Spanish. There are signs in Spanish everywhere, and two new soccer fields provide recreation for employees.

We discovered, not surprisingly, that there are problems, too. We found some evidence of racial profiling and a lack of understanding across the cultures. At times, when landlords realized that Hispanics often have an open-door policy of inviting friends and family to stay with them, they’d raise rents or avoid renting to them. One bank was reluctant to display copies of the area’s Hispanic newspaper in its lobby because the paper usually carried a picture of a sexy young woman. (After the bank complained, the next issue featured a picture of Padre Gene.) But the problems did not seem as great as I might have anticipated. For the most part, a region desperately in need of workers appears to be welcoming Hispanics. Our schools in Evansville were the first in Indiana with an International Newcomers Academy where Hispanic and other immigrant children are taught English as a second language.

In our reporting, we attended services in Spanish at Catholic churches as well as at Hispanic missions within other denominations, including Southern Baptist. We stood among mostly Mexican workers in Kentucky fields where farmers, unable to get Americans to pick crops, described their Hispanic workers as their “salvation.” Farm workers we met rarely complained, telling us that the work was no harder than back in Mexico and that many of them had grown up doing migrant farm work. By contrast, some of the factory workers admitted that their jobs were “dirty” or “hard,” but they liked receiving their paychecks. We met an Evansville attorney, a transplant from Los Angeles, who created a program to help low income Hispanics deal with legal and immigration issues. We heard tales of “coyotes” who were paid upwards of $1,000 to smuggle illegal immigrants across the border in what is a sometimes dangerous flight.

We met a sympathetic, cell phone carrying nun who apologized for feeling frustrated dealing with the same problems that Hispanics brought to her attention day after day. Often they needed help deciphering utility bills or figuring out how to seek medical attention. She was always there for them, including hospital delivery rooms, not caring whether the person was undocumented. “I close my eyes to that because I know the desperate situations so many are in,” she said. “They will put their lives in danger to come to America.”

“Señora Irene,” a Mexican American whose husband brought her to Indiana in the 1950’s, took us into Hispanic homes and introduced us to families. We wrote about 11 Mexican family members and friends living in a tiny trailer so they could send most of their paychecks back home. We also introduced our readers to Hispanics who had purchased homes and were advancing up the economic ladder—living the so-called American dream. We met a factory worker from Mexico who had just started a Latino newspaper and a Salvadoran couple who gave up their home and careers in engineering and nursing to come to America. They helped us to let readers know what it really means to leave one’s homeland “for the children.”

What we tried to do for our readers was put faces on the word “immigration” and convey the human experience behind changes we are all observing in our region. The highlight for me came one October evening when, amid pealing church bells, Narda Marmolejo walked down the aisle of a cathedral. It was her 15th birthday party, or quinceañera, and she looked like Cinderella at her ball, an event that amazed her Anglo friends. Narda’s parents toil in factory jobs to give their children opportunities they didn’t have. Her uncles and others helped her parents pay for the food, gown and mariachi band at the party after the religious service was over. We described how Narda’s parents cooked the meal in a copper kettle in the backyard and how her mother cleaned a sheep killed for her by a local farmer.

Reaction to our series was overwhelmingly favorable. Both Anglos and Hispanics said it presented an accurate picture and fostered understanding about such problems as the need for affordable housing and alcohol abuse among young Hispanic males. While our paper hasn’t carved out an Hispanic beat, we are certainly more aware of life within Hispanic communities and of the issues they confront. As for the questions that launched us on this journey, we’ve educated ourselves and our readers.

Yes, there are divisions and some animosity among Hispanics from different countries, but some of the tension stems from how our government regards their status in this country. And though Hispanic immigration in our area has been small when compared with many urban centers and other regions, we certainly discovered that we share a common experience in figuring out how to adapt when people of differing cultures, language and social perspectives become coworkers and neighbors.

Photos by Denny Simmons.

Reporter Rich Davis and photographer Denny Simmons were invited into the homes of Hispanic families who often shared living space so they could send most of their paychecks back home.

The newspaper’s series let readers know what “it really means to leave one’s homeland ‘for the children.’” Here Hispanic workers use a pay phone to call family they’ve left behind.

Rich Davis, a native of West Frankfort, Illinois, is a feature writer and occasional columnist at the Evansville (Indiana) Courier & Press, where he has worked since 1971. Denny Simmons has been a photographer at the same paper since 1999.