In an interview Sherry Turkle did with Aleks Krotoski for a BBC project, “The Virtual Revolution,” she spoke about how young people think about privacy and how their experiences with digital technology shape their connections and exchanges with others. View the entire interview »

RELATED ARTICLE

“Digital Demands: The Challenges of Constant Connectivity”

-Sherry TurkleEdited excerpts follow:

Sherry Turkle: This generation has a sense that information wants to be free and information about them wants to be free. People put their lives on the screen, they put intimate details of their lives out there with very little thought that there might be people using that information in ways that are not benign.

I interviewed a 16-year-old, and he talked about how he knows that people can read his e-mail. Somehow he senses that his texts are being saved in some server in the sky. When he wants to have a private conversation he goes to pay phones. He feels the pay phones are the only safe place for him to talk.

My grandmother, who came from a European background, taught me how to be a citizen at mailboxes in New York City. She brought me down to the mailbox and she said unlike in Europe where bad governments would read your mail and open your mail, in America it’s a federal offense to read somebody else’s mail. That kind of privacy is what gives you rights as a citizen.

In a way, I learned to be an American at these mailboxes as a kid. I don’t know where to take my daughter to teach her that. When we take the Mass Pike we use E-ZPass and surveillance cameras track my car. We’re both giving up unprecedented amounts of information and profiling.

It’s hard to teach the relationship between privacy and democracy; and it’s also hard to teach the relationship between intimacy and privacy. What is intimacy without privacy? I think this is a really important question for this generation.

Aleks Krotoski: It’s almost as if it’s a feedback loop: I give you a bit more information; you then give me more information, which then creates this incredible flood of information. As a recipient of all of this information, how do you think this is affecting me?

Turkle: You start to want to hide. At first, it’s all good. You get what seems like a virtual cycle of more and more and more; but as we see what this generation looks like as it grows up with it, we find they are now a generation in retreat. They’ll text, but they won’t talk. Philosophers tell us that we become human when we’re confronted with another face, with a voice, with the inflection of a voice; these kids don’t want to see a face, they don’t want to hear a voice. They want to text. In a way we’re no longer nourished but consumed by what we’ve created. It’s not all good. I see people in retreat as much as they are in advance now that they have all this information.

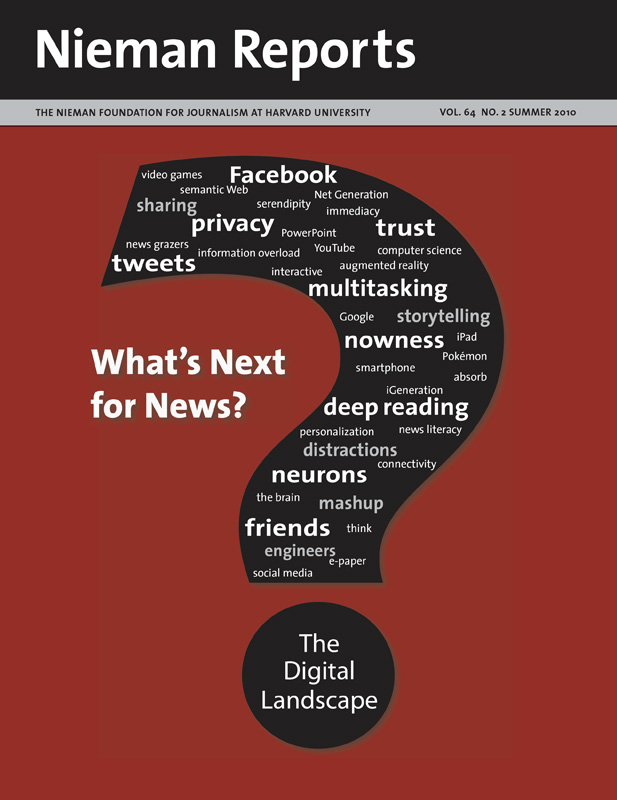

Krotoski: Do you feel that we are experiencing information overload or that we can parse it?

Turkle: Totally experiencing information overload. It’s become a cliché. In a word I see people defining a successful self as one that can keep up with its e-mail. There’s kind of a velocity and a volume that keeps people on a kind of hyperdrive of connectivity. In the end, they find a way to withdraw.

If the velocity and volume is such that I send you a tweet and I send you a text, then you have to answer me back. Nobody answers a text by saying I have to think about that for two weeks. The communication demands a response. But that means that we start to ask each other questions that are easy to answer.

We live in a kind of paradoxical time. We’re giving young people a very paradoxical message: The world is more and more complex; on the other hand, we’re only going to ask you a question that you can answer in two seconds. We leave ourselves less and less time for reflection because our communications media push us to quick responses. Quite frankly, the questions before our planet right now are not questions that should be answered or thought about in the time space of texting.