Sometimes looking back helps us to know more about why we arrived where we did. But this journey back in time can also be disheartening, especially when we discover that we don’t measure up to our potentials.

Take, for example, a few words I wrote in the Summer 1995 issue of Nieman Reports:

Journalists are entering a time of great possibility when more effective models of reporting, explication and discussion of the news can be built, with greater involvement of readers and a variety of new ways to present information. It is also a moment of severe peril, for if the established news sources do not understand how to both safeguard the credibility of their reporting and incorporate new ways of sharing what they know, their role in this evolving information society will be severely eroded.

I concluded: “The implications for a democracy are overwhelming.”

That journalism failed to move beyond the limited repurposing of the print and broadcast media and into the welcoming territory I wrote about—into places with an expanded sense of possibility—is beyond dispute. In part, this is because dissimilarities between digital and analog media weren’t taken seriously. Instead, repeatedly and almost universally we attempted to put what we’d previously done onto a screen-based template while marveling at the new efficiencies of the digital and simultaneously giving away our work for free. If this were Greek mythology, we—the know-it-alls in the journalism community—would be portrayed as having been devoured by a seductively ephemeral Web, not realizing it was much more than simply a substitute for “dead trees.”

RELATED ARTICLE

“Meditating on the Conventions and Meaning of Photography”I still remember a mid-1990’s Nieman conference in which Arthur Sulzberger, Jr., the new publisher of The New York Times, somewhat cockily announced that, while grateful to the Internet pioneers, the brand names had arrived and like Old West homesteaders would now be claiming the territory. But that brand name, like so many others, lost some of its place and reputation when available 24 hours every day, for free, in more or less the same form as on paper, and for too long relied upon its branding without recognizing that it also needed to be a pioneer. Nor did the Times’s self-righteousness help when its reporting was too soft on the Bush administration’s plans to invade Iraq without, as it emerged, any weapons of mass destruction to be found there. Those pesky pioneers writing blogs seemed, at times, more reliable.

I write this with regret because I was the one that the business side of the Times had asked in 1994, before the domination of the Web, to take a single daily issue of the Times and transform it into a multimedia platform in a project that lasted the course of a year. Back then, the Times online was charging foreign subscribers $30 per month. While our somewhat idiosyncratic model was initially popular among the newspaper’s management, the allure and uniformity of the Web was judged preferable, and the Times, like its competitors, joined the stampede to a reassuring homogeneity.

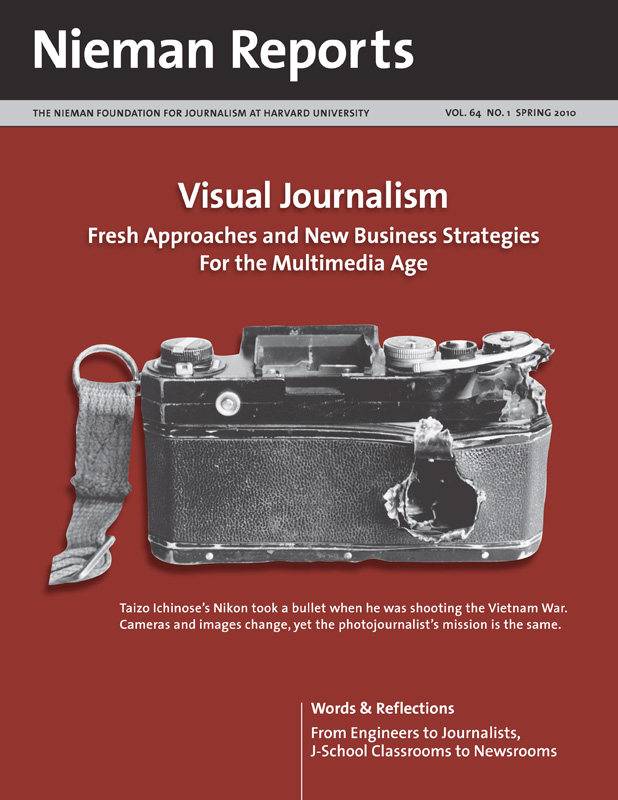

The Photograph—New Views

In our increasing desperation for audiences and advertisers, we also have been profligate with our major asset—authenticity. Nowhere has that been more evident than in photography, where an indiscriminate use of Photoshop has moved photography from a too-credible medium to one that is being repeatedly questioned and repudiated. Somehow we have reached 2010 without the reader or viewer knowing, despite every media outlet’s privately held guidelines, what each publication considers permissible to do to a photograph without distorting its initial meanings—a subject that I warned about in The New York Times Magazine in 1984.

Recently, the picture editor of one of our most reputable national publications, when asked in a public gathering by a professional photographic re-toucher to define the boundaries of ethical image manipulation, could only respond, “I will know it when I see it.” What then is the reader to assume?

Digital media give us ways not to depend upon the waning credibility of the photograph. On the Web, photographs may be contextualized so that readers can have a larger sense of what happened. Information can be embedded in each of the image’s four corners. Online viewers can make that visible by rolling over each corner with the cursor, thereby revealing substantial amounts of context. Not only can a factual caption reside at one corner, but the photographer’s personal opinion of what occurred can be found at another. Or an interview with the subject, pictures taken before and after, and links to other sites that might be helpful, including the photographer’s own Web site, could be hidden within the image for a curious viewer to explore.

As this photograph is shared—and re-published in multiple venues on the Web—all of this information travels with it, guaranteeing that the photographer’s point of view cannot be completely overridden by the accompanying articles.

None of this could happen on paper.

As well, there are enormous new possibilities for storytelling in the hyper-textual environment of the Web. Photographs can be layered so that the initial image is amplified and even contradicted by the second hidden underneath to give a more complex point of view (such as to reveal the staging of a photo opportunity with the second photograph underneath, or to show another perspective of an event such as the expressions of onlookers). It is possible to think of photographs or even pieces of photographs as nodes that link to a variety of other media, what I call hyperphotography, rather than as images that are sufficient in and of themselves. In this way, the reader becomes much more implicated in the unfolding of a story when she has to choose pathways to follow as a means of exploring various ideas, rather than being presented with only one possible sequence.

A large 1996 Web-based photo essay that I created for The New York Times online with photographer Gilles Peress, “Bosnia: Uncertain Paths to Peace,” did just that, leading one commentator to write in Print magazine:

Visitors cannot simply sit and let the news wash over them; instead, they are challenged to find the path that engages them, look deeper into its context, and formulate and articulate a response. The real story becomes a conversation, in which the author/photographer is simply the most prominent participant.

I would strongly urge that mainstream media involve others, including those at universities, in coming up with these new strategies. It is young people who are going to invent their own versions of journalism if it is to be revitalized and appeal to their peers. Just as the capabilities of the iPhone have been amplified in multiple directions by the tens of thousands of applications that people are writing for it, why can’t journalism be rethought and enlarged by opening it up to new ideas and strategies from the non-professionals? This, in fact, might be the most salient contribution of what so many call “citizen journalism.”

Fred Ritchin, a professor of photography and imaging at New York University, is the author of “After Photography,” a book about the new digital potentials that is being translated into Chinese, French, Korean and Spanish. His blog is www.pixelpress.org/afterphotography.