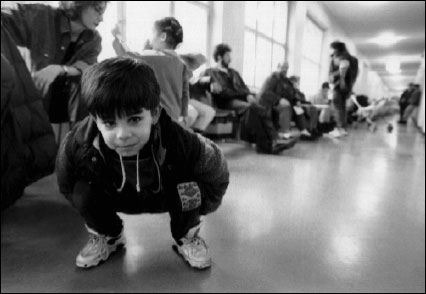

A boy waits with his mother in the hallway of a welfare office in Berlin. Photo by Katharina Eglau.

Ideas travel. Historically, political entrepreneurs on both sides of the Atlantic have pointed to the effectiveness of practices that were developed on the other side as evidence of the feasibility of their favored policies.

In the 19th Century, Friedrich List, long-time German advocate for national tariffs, went to the United States, became actively involved in the American tariff debate, and on his return campaigned for the adoption of a national economic strategy on the basis of the American success. At the turn of the century, the U.S. Chamber of Commerce wanted to import the German apprenticeship system, so officials came to see and report on how it worked.

In the 1920’s, German Social Democrats and union leaders were fascinated by Henry Ford’s production philosophy, prompting the radical labor intellectual Jakob Walcher to write a book entitled “Ford or Marx: The Practical Solution of the Social Question.” Ford’s memoirs appeared in German translation in 1923 and ran through more than 30 reprints. Under the Nazis, Ferdinand Porsche toured Detroit’s automobile factories in search of ideas for his Volkswagen project. After the Second World War, Germans considered almost anything American a model for imitation. By the 1970’s, the so-called “Wirtschaftswunder” and the competitive edge enjoyed by German companies convinced American business leaders to look at the “Modell Deutschland.”

Now, America’s low unemployment and economic strength of the 1990’s have ignited a broad discussion in Europe on the merits of the U.S. model.

As the first political waves of Clinton’s vague ’92 campaign slogan “to end welfare as we know it” reached European shores, U.S. unemployment figures dropped below German figures for the first time since the early 1960’s. Led by its young, dynamic president, the United States seemed willing to become fit for the global competition of the next century by rethinking the traditional balance between the welfare state and its citizens, between public and private responsibility. The political and journalistic response was swift and comprehensive. Mainstream coverage in the German press focused on several features of the U.S. system that—if transferred to this country—could bring about a change of course in its economic and social policies.

Welfare reform measures—such as state-sponsored workfare projects—were examined with an eye toward their applicability in Germany. Along with looking at specific welfare policy changes that were taking place in states like Wisconsin, other economic and social issues were being covered as well. These included the sudden surge in U.S. jobs, wage restraint and social deregulation, the entrepreneurial spirit in the United States and the abolishment of the alleged welfare hammock for the poor.

Now, two years later, the situation has changed. The U.S. job situation appeared to lose its attraction when reporting about the dark side, the undesirable side effects of the American success story, started to show up in newspaper editorials and magazine stories. One reason for this change was that leading publications describe and treat the American welfare situation as an issue that is closely interrelated with other features of social policy like, for example, health care and the minimum wage. It is unthinkable in most European states that so many people would be without health insurance and work for such low wages without receiving government benefits.

Other topics that surfaced in reporting about American social policy included high crime and poverty rates (especially among children), large wage disparities, the working poor, dismal employment protections, and low levels of unemployment benefits. And there was also coverage about the subsidies companies receive from the government through the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC), which enables low-wage workers to inch out of poverty.

The leading motto for European journalists became “The devil is in the details.” Reporters didn’t pick out isolated elements to portray as models of social policy but instead scrutinized the whole picture of American social policy, and this became the focus of comparative coverage. And this was set against the backdrop of recognizing that societies whose perspectives arise out of very different cultural backgrounds have great difficulty in adopting other countries’ models.

For these reasons and more, the once-popular recommendation of adopting the American approach to transforming the welfare system has been pushed to the side among politicians and business leaders. In turn, mainstream press coverage has evolved a skeptical distance, quite different than during the early Clinton years.

The short-lived enthusiasm for the U.S. model has not vanished completely, however. Certain traces of it remain. While the question of a direct transfer of U.S. welfare or employment policy has dropped from the agenda of European leaders, two subtle trends of American political thinking are taking hold in most European countries, and reporters are starting to cover them.

First, Europeans appear to be drawn to the “behavioral approach” of this new generation of U.S. social policies that are the centerpiece of Clinton’s welfare initiative. President Clinton stressed the view that welfare policy is a contract between society and the individual, with the citizen doing his or her part to end dependency on public funds. This led to a politics that played on society’s desire to see that people change their personal behavior, go to work, do whatever they can, before they put their hand out to the public. This attitude made possible the bipartisan passage of legislation such as EITC, but it also led to the wide-scale introduction of sanctions imposed on those who do not get a job.

Imposing financial sanctions on people who depend on public help has almost always been a taboo in European welfare policy and thus has been portrayed that way in much of the past coverage. But this is no longer the case as reporters are taking their cues for story angles from the dramatic changes in the political environment since “New Left” governments have come into power in Britain, France and Germany. As a case in point, in March the head of the powerful German Metal Trade Union asked, together with several leading politicians, for strict welfare sanctions against youth who refuse to participate in the federal “100,000 jobs” program. While party officials proposed and debated a 25 percent welfare cut, the union, the most powerful of its kind in Europe, demanded a total cutoff, something that would never have been heard at other times in German political discussion. This debate quickly became front-page news.

The second influence on American social policy thinking pertains to the traditional social security mentality of European welfare systems. The use of “means testing” (assistance provided based on the financial situation of the person or family in need) as a way of determining the point at which public support is merited seems to be gaining in popularity. In the United States, many benefits such as Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF), food stamps, housing subsidies and health insurance are means tested.

In most of the European countries, social benefits like unemployment insurance, child credits, pension payments or health insurance have the characteristics of a public social security payment to which all are entitled regardless of their financial situation. Facing considerable budget deficits and strict financial limits set by the new European Central Bank, a shift to a predominantly means testing system is on the public agenda of many European states as political resistance subsides. Once again, the topics and tone of media coverage reflect this new and significant shift that has occurred in thinking about this aspect of social policy.

Right now, the United States’s impact on all of this is less and less openly acknowledged in media coverage and public debate about European policies on welfare. This is caused, in part, by European’s current self-absorption that has resulted from the introduction of the Euro currency and the concurrent need to harmonize the main features of each nation’s economic, tax and welfare systems. This situation has triggered much more intensive coverage of the social policy agendas of European neighbors at the expense of reporting on the superpower across the Atlantic. Larger European countries, in particular, now look primarily to smaller ones for new ideas and reform approaches; Germany, for example, looks to the Netherlands and Denmark.

One of the more intriguing topics that has captured media interest is the new, flexible culture of cooperation and roundtable politics between companies and trade unions that these countries are experiencing. This kind of story would be unlikely to emerge if the focus had remained on the United States because relations between labor and management are traditionally more hostile there. And in these smaller European countries there are plenty of other stories to be found, such as ones about their remarkable success in job creation, reduction of welfare dependency, and empowerment of weaker segments of the population. At least for now, these are the stories European journalists appear eager to report, and when they do, the viewers and readers aren’t confronted by the kind of distressing news that seems to accompany stories about America’s transformation to a new social contract.

Martin Gehlen, a 1992 Nieman Fellow, is editor and writer for domestic issues at Der Tagesspiegel in Berlin. His 1997 book, “Upheaval in the American Social Safety Net: The 1996 Welfare Reform From a European Perspective,” was released in Germany.