Cameraman Ziad Tarraf drove a white van festooned with bright red PRESS written on its sides to my Beirut hotel early one August morning. The war between Israel and Hezbollah had just ended in an inconclusive draw, and we were embarking on a two-week shoot of "Deserted Riviera" that would take us from the scarred cement canyons of Beirut to the shelled and pockmarked villages of southern Lebanon before reaching right up against the border with Israel. Along the way, we had to grapple with the conundrum of how to represent all sides in a notoriously complex conflict and present them engagingly to a war-fatigued audience.

During our shoot we interviewed a colorful set of characters. There was the blonde TV producer cum socialite who told us that "It was going to be the best summer since the 70’s. And there were going to be loads of events, huge artists coming from above, and people were really looking forward to it because they had been hit economically [by the instability]." In the still-smoking ruins of Beirut’s Hezbollahstan, an outraged Syrian war-tourist railed impotently against the West: "If not today, then after 20 or 100 years we will have died, but the coming generations will be our guarantee against the West. These sights that you’re seeing here will happen to them in their own countries," he said, waving at the collapsed apartment towers and flattened vehicles. A few kilometers away, we encountered a similarly livid Lebanese neoconservative and his Arabic-speaking Austrian wife. But despite condemning Hezbollah for triggering the war, Lokman Slim refused to abandon his family mansion in the heart of Shiite Beirut.

In South Lebanon, we witnessed a crippled Lebanese informer for Israel stranded in his wheelchair in the no-man’s land between the two countries, begging the unheeding Israeli Defense Force (IDF) soldiers to let him in. With the war having ended inconclusively for Israel, dozens of Lebanese collaborators, who were terrified they’d be revealed, made a run for Israel. On the Lebanese side, Hezbollah intelligence agents leaned against an old-model Mercedes, waiting for the informer to exhaust his last drops of water and come back to their tender mercies. In a classic example of how journalists are used in conflict situations, they asked us to accompany them into the mined no-man’s-land as they tried to snatch the informer, no doubt thinking that a foreign journalist escort would minimize their chances of the IDF targeting them.

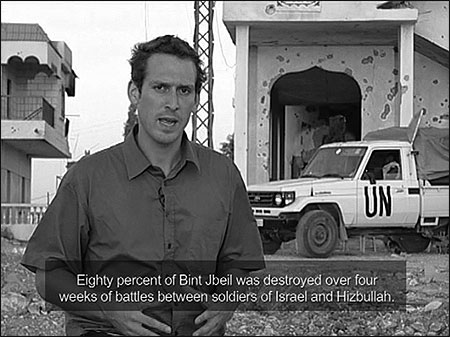

In the shattered village of Aita al-Shaab, we interviewed a local who remained through five weeks of street fighting among the ruins, as he resupplied Hezbollah fighters. A shell-shocked but straight-faced girl told us how a group of shabab (Hezbollah youths) donned Israeli Army uniforms to infiltrate and exterminate an Israeli outpost within their village. And in Bint Jbeil, another once-contested, now-devastated town, we saw how several weeks of fighting destroyed over 80 percent of it. Finally, we returned to Beirut and concluded the film in Beirut’s nightclubs, with a euphoric postwar disco scene that communicated some of the schizophrenia that being Lebanese entails.

Appealing to Young Audiences

In Athens, Greece, our film’s director, Christos Karakepelis, edited the 20 hours we’d shot to a frenetic 28 minutes. Trying to tell in less than half an hour the story of how Hezbollah claimed a strategic victory from the war and the political lift this gave the country’s Shiite community seemed imprudent and foolish. But in Greece, a country where the corporate news media features detailed coverage of the Middle East only when conflict erupts, our first priority was to claim the MTV generation’s attention — and to do this, we knew, meant keeping things moving and keeping things short.

With the introduction of private TV stations in the 1990’s, and an influx of U.S. primetime shows such as "Baywatch," "Beverly Hills 90210" and "The Bold and the Beautiful," Greek audiences became accustomed to a diet of celebrity news, reality shows, and Latin American soaps. To the extent that the Middle East impinges on their consciousness, it is as a perennially chaotic region peopled by crazy Muslims, largely beyond any hope of comprehension or salvation. This is an impression promoted by most Greek journalists who sally forth to the region only in the event of war and lack both an understanding of its specificities and the budgets needed to cover it well. While most channels maintain a Turkey correspondent, hardly any Greek journalists live in the Middle East.

Karakepelis and I decided that if we wanted "Deserted Riviera" to illuminate the complexities and subtleties of Lebanon’s politico-religious tapestry, we’d claim our audience’s attention through engaging characters and fast-paced visual units.

One of these characters was Lokman Slim, the aforementioned scion of an old Shiite family rooted in the Shiite-dominated Haaret Hreik. He conjured up a pre-civil war cosmopolitan neighborhood transformed by rampant sectarianism into a stronghold for Hezbollah. Along with his wife, Monica, they refuse to abandon their war-worn villa that doubles as a cultural center called Umam (Nations). Slim dislikes Hezbollah but refuses to be bought out of his property by its agents. His cultural center, he believes, can act as a counter to what he describes as a fanatical Shiite monolith.

After mentioning that I was based out of Tehran, Slim looked me over dubiously and lectured me on the mendacity of the Iranian project in the Middle East. Monica gently took me through the cement-dusted garden on a tour of the destruction that rained upon the villa and its valuable newspaper archives during the nightly Israeli bombardments.

"Everything was full of smoke when we arrived," Monica recalled of the night that their house was hit. "The first impression was a little bit ‘Apocalypse Now.’ There were no doors, no windows, everything was flying around, the trees were broken, and it was total disorder."

This kind of destruction was on view throughout the country, especially the further south we traveled. Passing the bombed-out electricity generating station of Jiyyeh and a multitude of downed bridges, it became increasingly clear that the Israeli air force had targeted Lebanon’s infrastructure as much as that of Hezbollah.

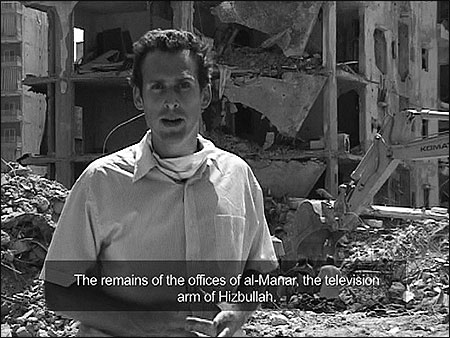

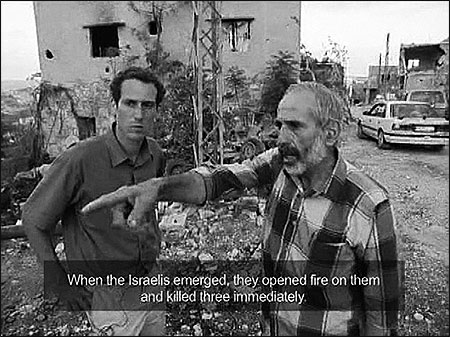

In the devastated village of Aita al-Shaab on the Lebanese-Israeli border, an elderly resident named Muhammad Dakdouk, a member of Hezbollah’s resupply unit, freely offered to share his story when he came upon us filming the shattered streets two weeks after the end of the fighting. "The sons of the Party [Hezbollah] are our children," Dakdouk declaimed. "We are the Party, not someone foreign coming from outside, like Iran or Syria, as the Israelis charge." The father of an absent Hezbollah fighter, Dakdouk pointed to where his son had killed three Israeli soldiers and showed us a grisly collection of Israeli medical supplies — blood pouches and bloodied uniforms that the IDF left behind after occupying his house.

The blow-by-blow account of ferocious fighting Dakdouk witnessed was a rare on-camera testimony to a Western channel by a member of Hezbollah. Delivered in front of a backdrop of almost apocalyptic destruction, it made for compelling TV and added a human dimension to what is a largely faceless movement, characterized in its public manifestations by fascist-like rallies. But Dakdouk was also revealing to our camera the flip side of Israel’s military venture into Lebanon that people in Tel Aviv would have avoided highlighting.

A Valued Colleague

Our cameraman, Ziad Tarraf, was not just courageous, committed and creative in tackling his task. He was also the stiff upper-lipped citizen of a country under dismantlement, sticking to his work amid great destruction. The child of a Shiite family from the South, he was a member of Hezbollah into his teenage years. At some point, he weighed his future and left the organization to pursue his dream of becoming a cameraman.

In the South, his family name was known and respected. Having him as a part of our film crew allowed us to move unfettered through a still-smoking war zone and conduct on-the-spot interviews with anyone we chose. This kind of access marked an extraordinary departure in a region notorious for the draconian limitations imposed upon journalists. Usually throughout the Arab world journalists are shadowed, snooped on, and even detained on allegations of spying.

In Israel, the army had imposed strict military censorship throughout the fighting and has restricted access to the news media in the Gaza Strip. During the past few years, several Palestinian journalists working for local and foreign news media have been killed by Israeli bullets in the occupied territories.

In Lebanon, Hezbollah kept journalists out of al-Dahieh during the war and then after it ended monitored their movements. But for us there were a few golden weeks that summer when Hezbollah embraced — either through an enlightened policy or the chaos of reconstruction — more open media access compared with what is typical in the rest of this region. Perhaps through this experience, Hezbollah’s leaders will have understood better the value in having their people’s stories shown and told.

Iason Athanasiadis, a 2008 Nieman Fellow, directed "Deserted Riviera," which won third place in the documentary category of the 2007 ION International Film Festival in Los Angeles. For the past several years he has been based in Tehran, writing for and providing photographs to Western news organizations, as well as to those in his home country, Greece.