At an April 11, 2007 press conference, North Carolina Attorney General Roy Cooper announced that the three young men accused in what had come to be known as the Duke lacrosse rape case were “innocent of these charges.”

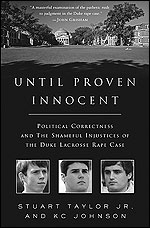

Reade Seligmann, Collin Finnerty, and David Evans might have been innocent, but there was plenty of guilt to go around. Stuart Taylor, Jr. and KC Johnson make that clear in their book, “Until Proven Innocent: Political Correctness and the Shameful Injustices of the Duke Lacrosse Rape Case.” Their list of what went wrong is a long one and, while the actions of Durham District attorney Michael Nifong would have to be at the head of it, the news media’s coverage of this story is not far behind.

It’s true that Nifong—called a “rogue prosecutor” by Cooper—branded members of the lacrosse team “hooligans” before any charges were brought against three team members. He withheld exculpatory DNA evidence from the defense. As a result, he won support and votes from black Durham citizens with his manipulation of the case.

After the first accusations that white members of the lacrosse team raped a black woman hired to strip for them—a woman who was also a mother and a student at North Carolina Central, an historically black university in Durham—Nifong recognized what it could mean for his career. But it would have been difficult for him to pursue his cynical agenda without assistance from compliant media. Nifong was eager to make his case—one short on evidence—in the newspapers and on television.

Members of the media obliged. Journalists—and cable TV pundits—lapped up sound bites and quotes. In March 2006, when the story broke, I was far from North Carolina and my job as a columnist and editor at The Charlotte Observer. My body was in Cambridge, Massachusetts, and my brain was coming to terms with the rapidly approaching end of my Nieman year. I couldn’t ignore the news coming out of Durham and Duke. No one could. This was the lead story on every cable TV show and front-page news, from the tabloids to The New York Times.

The story had everything: race, sex, class and privileged athletes at an elite institution. What disturbed me from the beginning was what it didn’t have—the ring of truth. Something was off. I knew it. I felt it.

My son graduated from Duke University in 2005, long before most people had heard of the school’s lacrosse team. I had spent some time in the city and at the school, as a parent and a journalist. The public profile on display was a caricature of what our family had experienced. I spelled out the contradictions in a column I wrote upon my return to North Carolina.

RELATED WEB LINK

Read Curtis’s column on contradictions in the Duke lacrosse rape case »

– charlotte.com/The script soon became set in stone: poor, black townies vs. white, wealthy preppies. The story was less sexy if a reporter decided to write about a city diverse in color and income. There were tensions, to be sure, between the area’s largest employer and the citizens of the town. But Duke students were also involved in Durham life, volunteering to tutor in the schools and register voters. There were more black students—slightly more than 10 percent—at Duke than at many private universities. It costs more than $40,000 for a year at Duke, a fact stated often in news coverage. Not many stories mentioned that more than 40 percent of the students receive financial aid. My son, like others, attended the school on scholarship.

While I didn’t excuse boorishness, underage drinking, and hiring strippers, behavior members of the lacrosse team admitted, I didn’t see it as evidence of rape. I searched the articles for balance, for facts—for solid reporting. What I found was prejudgment and stereotypes. It’s not as though I am unaware of this country’s shameful history of exploitation and abuse of black women, through slavery and beyond. And as a black woman, I also knew there might be more to the story of the woman at the center of the case, dismissed as an “escort.”

Yet I was uncomfortable that journalists were using that history as a ready-made frame. In “Until Proven Innocent,” Taylor and Johnson carefully recount the sorry episode. Taylor is a columnist for the National Journal and a contributing editor for Newsweek, writing about legal, policy and political issues. Johnson is a history professor at Brooklyn College and City University of New York, who has written more than 800 posts of analysis about the Duke case on his blog.

RELATED WEB LINK

Taylor’s blog, Durham-in-Wonderland

– blogspot.com/Their view of this case tilts conservative, and their targets also include what they see as political correctness run amok on college campuses across the country. They lambaste some Duke professors, particularly the Group of 88 who signed a newspaper ad asking, “What does a social disaster look like?” that linked the case to racism and sexism at Duke.

That all the elements were too good to be true should have been a warning to journalists. But as they parachuted into Durham, looking for an angle and a scoop, it became clear that the opposite was true. The Duke student newspaper, the Chronicle, was closest to the students and the case. Ironically, it was student journalists and columnists who urged caution and attention to the facts. The New York Times set the tone of its coverage early. An April 1, 2006 headline read: “A Team’s Troubles Shock Few at Duke.”

In August 2006, as Nifong’s case was crumbling, the Times ran a lengthy, front page reassessment, based substantially on notes presented by the lead detective months after his initial investigation. Not surprisingly, the detective’s memo supported Nifong’s case. But Times columnists David Brooks and Nicholas Kristof had started, by then, to raise questions. Newsweek, which early on put mug shots of Seligmann and Finnerty on its cover, later published “Doubts About Duke,” which dissected Nifong’s unraveling case. Cable TV, usually preoccupied with crime when the woman in peril is white, blond and attractive, emphasized every sensational element of the Duke case, with former prosecutor Nancy Grace leading the charge. The faces, names and reputations of the suspects were fair game, while the identity of the alleged victim was protected.

It’s not as though anyone could say “we didn’t know better,” as relevant facts—such as black Duke law professor James Coleman’s largely favorable report on the culture of the lacrosse team and his damning criticisms of Nifong—were ignored or downplayed. They didn’t fit the frame.

After April’s verdict, there were few media corrections or apologies. It took someone labeled a wealthy, white entitled preppy, Reade Seligmann, to finally express concern for “people who do not have the resources to defend themselves,” after the charges against him and his teammates were dropped.

I began to understand why some mistrust the news media, who were so off on a story I knew something about. What about the others? Michael Nifong’s claim to fame might be contributing a new word to the language—to be “Nifonged” means to be “railroaded.” Stripped of his law license, the disgraced district attorney eventually paid a price. In terms of their credibility, so did journalists.

Mary C. Curtis, a 2006 Nieman Fellow, is a columnist at The Charlotte (N.C.) Observer, a contributor to the Nieman Watchdog Project (www.niemanwatchdog.org), and an occasional commentator on NPR. Her Web page address is www.charlotte.com/333/index.html.