It is said that journalism is a blunt tool and has trouble handling the subtleties of issues. Maybe. But there are times when the hardest things for journalists to handle are not subtleties, but the most blatant falsehoods, the biggest whoppers.

That is because reporters daily pass on what leaders say with a fair amount of trust in those who are speaking. When government officials, or the think tanks that sometimes support them, issue reports and hold press conferences, it is assumed that some essential academic honesty is present in the research and recitation of facts. Details or arguments might be debatable. But reporters are handy at finding opposing views and counterfacts for those.

Challenging Falsehoods

It is when the tales being put out are cut from whole cloth, from big assumptions to fine details, that the reporting becomes much harder. Reporting that a new study is, in essence, a blatant falsehood is actually quite hard. It puts the journalist in the position of challenging the source directly, a position no reporter or editor finds comfortable. Reporters in the mainstream media are trained to be observers, chroniclers, not combatants. And to knock down larger falsehoods requires not just a day or two of calls and interviews. It requires some real digging.

Some excellent examples of reporters trying to combat larger falsehoods come from the field of government regulation. In America, where conservative market economics is king, some of the greatest whoppers are told about the dreaded “federal government regulators.” I followed the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) as part of my beat for 20 years, first for The Washington Post and then for The New York Times, and I can tell you that there is a good bit of blarney spoken of the FDA.

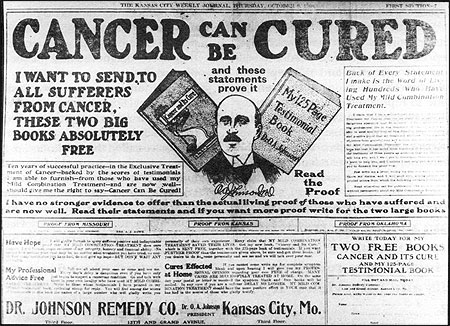

Let me cite one example first to make the point. From late 1994 to 1996, an intense “anti-regulatory” campaign was carried out in Washington, led chiefly by Representative Newt Gingrich and a number of very conservative foundations. They put millions of dollars into attack advertising and attack P.R. campaigns against the FDA. One example of the ads was the one run by the Washington Legal Foundation that read: “If a murderer kills you, it’s homicide. If the FDA kills you, it’s just being cautious.” Use of the phrase “deadly regulation” to refer to the FDA became common. Gingrich called FDA commissioner David Kessler “a thug and a bully.”

As part of this campaign, bills were proposed in Congress to strip the FDA of its regulatory powers and to end the “murder by regulation.” What the new regime proposed was to let drug companies police themselves by hiring their own reviewers to check the safety and effectiveness of their products. In aid of this “FDA reform” the pharmaceutical manufacturers of America staged a “fly-in”—bringing 140 “real people” who had been hurt by the FDA to Washington to testify and to visit Congress.

To many reporters covering health and science in Washington, this fly-in had a bad smell about it, as did the wild claims of the death and injury caused by FDA regulation. But few reporters had the nerve or time to challenge the rising tide of anti-regulatory rhetoric.

One who did do the work was John Schwartz of The Washington Post. He decided to take the time to interview a number of the people flown in. The pharmaceutical companies gave him a list, presumably their very best examples. But when Schwartz interviewed them, it turned out that they were not damaged by FDA policies and would not be helped by the “FDA Reform” being proposed, either. Most of the patients’ problems were, in fact, with their insurance. The drugs they wanted had been approved by the FDA, but the insurances companies wouldn’t pay for them. The whole “reform” fly-in turned out to be a whopper.

The Schwartz story was unusual then and would still be considered so today. Back then, I recall there were occasional news stories that got behind the veil on this issue, one in The Washington Monthly and one in The New York Times. But, overall, the coverage was superficial. Many read like this: “… the conservatives say the agency is holding up life-saving drugs and their opponents said the reform bills would gut the agency and threaten safety,” all said without substantive examples provided.

Since most newspapers and broadcast programs don’t have specialists reporting on what are considered second-tier agencies, and the reporters who cover them often aren’t given the time to report deeply on such issues, the general weakness of the coverage is not surprising. Most news is telegraphic, bulletin-like. Readers who want more have to search out the more thorough stories. Of course, this sounds like criticism of journalistic practices in general, but it is hard to imagine a journalistic system that would be much different. For the most part, news organizations do provide just the alerts; magazines, books and scholarly work must be relied on for the rest.

This 1908 fraudulent newspaper ad led to a Supreme Court decision that the FDA could not crack down on therapeutic claims. In response, President William H. Taft asked Congress to override the decision. It did, but prosecuting such claims remains difficult. Courtesy of The Office of History at the Food and Drug Administration.

Misinformation About the FDA

In covering various medical and science issues during the past three decades, I believe more such misinformed campaigns have been mounted against the FDA, and perhaps the Environmental Protection Agency, than any other agencies. This is, perhaps, in some way related to the level of journalistic scrutiny that I alluded to above, which these agencies are usually given.

I have accumulated dozens of FDA examples in my files. Here are just a few historical examples:

- Ronald Reagan suggested at a press conference that the FDA might have killed 40,000 Americans because the agency had not approved a new tuberculosis drug. In fact, the FDA had approved the drug five years before Reagan’s press conference and had approved it within months of the time the application came in. As for the numbers: In the entire decade between 1968 and 1978, 28,000 people died of TB, largely because they were diagnosed late in their disease.

- Gingrich and the conservative Washington Legal Foundation said Americans were suffering greatly when the FDA didn’t approve a new medical device called the CardioPump. It was to be used instead of regular human CPR techniques. In national advertisements, the foundation said 14,000 people died because of the FDA failure to approve the device. Gingrich railed against the FDA. But medical studies never showed the expensive device worked any better than regular CPR; early studies showed that it caused some damage to the chest and, in 18 percent of cases, it slipped off and valuable time was lost in resuscitation.

- The Washington Legal Foundation also wrote in national advertisements about the drug tacrine. It is now used to give very small and temporary memory improvements in early Alzheimer’s cases. The foundation said: “During the seven years it took to approve tacrine, thousands of Alzheimer’s patients gradually lost their memories. Nobody knows how many died.” Tacrine would not have prevented any deaths. Nor does it halt the progress of Alzheimer’s. Worse, it was the FDA that was first in the world to approve this marginal drug.

The story of “runaway regulation” repeated in conservative political mythology over the past 25 years has another side. Not only are the regulators bad, but also the companies that are regulated are, in fact, the chief risk-takers, the ones who really bring life-saving drugs to Americans. The government is just a barrier to such development.

But history does not bear out this argument. Two prominent examples:

- The greatest drug breakthrough of the century, penicillin, is often counted as an example of a coup of drug company research and manufacturing. In fact, when British scientists had the first batches of a workable penicillin in hand in May 1940, they took them to one drug company after another, offering the brilliant discovery for free to any company that would do the development and marketing. British companies turned them down, and the scientists flew to the United States, certain that the wealthy Americans would jump at a chance to market the miracle drug. American companies turned them down flat. Too risky an investment, they said. Instead, the scientists turned to scientists working in government labs; they accepted the challenge the same day it was offered, and during the next year carried out the most crucial work in the drug’s development. Then, after the United States entered the war, the U.S. government asked the companies to join in now that important progress had been made. The companies still balked. Finally, they were all but ordered to work on penicillin for the sake of the troops. The companies were given financial incentives as well and, finally, belatedly, agreed to work on penicillin.

- After the AIDS epidemic started and was identified as a viral plague, scientists and public health advocates urged American companies to begin work making anti-AIDS drugs. But the companies balked; the investment was too risky. Perhaps the epidemic would go away, or not enough people would get sick to make a drug profitable, analysts said. So it was that the first three vital drugs against AIDS came not from industry but from work in government laboratories.

Reading the record of regulation closely, it appears that the tale of the terrible regulators is just that, a tale. It has sprung from a belief in a too-simple theory of economics, the market ideal. But this belief holds great sway in America in these times.

Disputing the ‘Tale’

Because of the conflict between the tales and the facts of food and drug regulation that I kept finding in my reporting, eventually I decided to document it in a book. I found that the true story of regulation and business has been that modern medical science has moved forward by willing and unwilling cooperation between them. Modern medicine could not have happened without this synergy. The role of the regulator was not that of a barrier; it was that of a goad. Regulation set high scientific standards that businesses never would have set or met on their own, and progress has depended on high research standards. Without them, the proof that an advance is really an advance might never come.

Of course, the tales of the terrible regulators go on. And young journalists are faced with the same difficult choices. They can quote those who are telling the “tale” and move on, while trying to bring to bear skepticism they might feel. Or they can take a risk—ask for extra time and try to dig up facts that can put these “tales” in their proper context. Take this route and they might irritate editors, sources and the organizations they are questioning. And they might mark themselves as problem cases, especially if they fail to document their suspicions and end up with a weak story or no story.

Chasing this second kind of story is a lot harder. But once in a while, setting the record straight on one or two whoppers can make the risk worth it.

Philip J. Hilts, a 1985 Nieman Fellow, has covered health and science for The New York Times and The Washington Post. He is the author of five books. His most recent is “Protecting America’s Health: The FDA, Business and One Hundred Years of Regulation” (Alfred A. Knopf, 2003).