Emmanuel Moise, left, 14, Ernest Moise, 40, and Daniel Moise, right, 17, have received asylum while the children’s mother and sister are being detained by the INS after arriving from Haiti on December 2001. The Moises hope their relatives will be released and not sent back to Haiti. Photo by Carl Juste/The Miami Herald.

Thomas Sylvain didn’t have much of a chance. Because of his criminal record, the Miami INS District deported him to Haiti in January 1999. No one knew then that he was HIV positive. The fatal mistake was that he shouldn’t have been deported at all: Thomas Sylvain was a U.S. citizen born in New York.

Immigrant advocates protested his deportation at the time. Yet his deportation officer and INS superiors doubted Sylvain’s claim to citizenship. Yves Colon, the Herald reporter then covering immigration, wrote a number of articles as advocates, family members, even the Haitian Consulate in Miami, continued to complain about how the INS had deported Sylvain. But the INS left it to The Miami Herald to produce the documents that proved Sylvain’s citizenship. Colon tracked down Slyvain’s father, who gave him Sylvain’s original birth certificate and U.S. passport.

At that point he had been in Haiti two months and already it was too late. By the time the INS admitted its mistake and flew him back to Miami in May, Sylvain had full-blown AIDS. He went into cardiac arrest in the ambulance taking him from the plane to Miami’s public hospital. He died not long after.

Now, more than three years since his death, the INS hasn’t yet explained why this tragedy happened. INS documents responding to a Freedom of Information Act request by Colon arrived all blacked out, except for occasional prepositions. And the public has no assurance wrongful deportation won’t happen again.

But then, that’s not unusual for immigration matters in south Florida. Though the public has a right to know why the INS sets a certain policy, how abuses happen, who was responsible, and what has been done to prevent more misconduct, that information often must be dragged out of the agency by the press, immigration advocates, the courts, even hunger strikers. Post-September 11, we’re experiencing and witnessing similar battles for access and transparency writ large.

Of course, none of this secrecy has helped shape an effective instrument of the nation’s complex and contradictory immigration policies. Power without public scrutiny has instead bred lack of accountability, incompetence and abuse. The INS suffers from an inbred culture that shields malicious employees and incompetent managers—so much so that internal investigations drag for years and results aren’t publicly made known.

The INS’s Krome facility, a longtroubled detention center on the edge of the Everglades, is illustrative. In 1992, a number of INS staffers complained that Joe Kennedy, then Krome’s chief detention officer, had used a stun gun against a male deportee in the groin area. Witnesses said that the act set off a melee in which three officers ended up injured. A subordinate also said that Kennedy had tested the weapon on him. Yet stun guns aren’t issued or authorized for use by INS detention officers.

But none of this was investigated until five years later and then only because the episode became public. Herald reporter Andres Viglucci had heard about the stun gun before from INS officers who knew him from his numerous stories about misconduct at Krome. Eventually, INS sources contacted him, willing to go on the record after the shenanigans quietly came out during an INS employee’s unrelated grievance complaint.

Viglucci’s meticulously reported story quoted one of the witnesses as saying, “Who was I going to report it to? My entire chain of command was involved.” At that time, the witness had verbally complained about the stun gun to Kennedy’s bosses, he said. The witness was reassigned soon afterward, and when his contract for temporary work ended, it wasn’t renewed. The detainee hit with the stun gun, and the detainees who saw it, weren’t around to complain, either. They had been deported after the incident. Only after the incidents were exposed in the press did the INS begin an investigation, removing Kennedy from his post for the duration.

That’s not to say that all INS employees are corrupt or incompetent. In covering immigration issues since 1997, I’ve met a number of INS professionals who balance the law, common sense, and compassion. Many have called me and other reporters who cover immigration to give us tips or simply vent. They have a tough job enforcing unpopular Congressional mandates. It’s too bad that their good work is undermined by INS staffers and managers who abuse their power and tolerate intolerable abuse.

South Florida knows those INS dysfunctions better than most places. Census 2000 figures show that Miami-Dade County has the highest concentration of foreign-born residents of the nation’s major metropolitan areas: 51 percent out of 2.2 million people. And as those foreign-born populations have grown, so have the proportions of people who are naturalized citizens in Miami and Fort Lauderdale metro areas—most notably to some 23 percent of the population in Miami-Dade alone.

With so many immigrants, the INS comes under intense questioning by the public. Immigration advocates and others with complaints about the INS are not shy about contacting the press, either. There are more stories than reporters could hope to cover. We write what seems endless articles and editorials. Any improvement, however, is difficult to gauge because old problems, like problematic INS employees, don’t go away.

Remember Kromegate in 1995? That’s when Miami INS staffers prepared a cover-up for a congressional tour. Days before its arrival, Krome was so overcrowded that 55 women were sleeping on cots in the clinic lobby. After the INS transferred or released more than 100 detainees, lawmakers saw significantly improved conditions that distorted reality. The scam was discovered when 45 offended INS employees blew the whistle in a letter faxed to Congress and later released to the press.

By 1996, federal investigators had concluded that local INS officials deliberately set out to hoodwink the congressional delegation. The evidence included an e-mail from Constance Weiss, then Krome chief, which said that detainees had been “stashed out of sight for cosmetic purposes.”

Of the five INS executives recommended for the stiffest discipline afterward, four remain with the agency today in high-level jobs. Most, including Weiss, were cleared by the U.S. Merit Systems Protection Board. Weiss downplayed the e-mail as a “flippant” remark and maintained that she “didn’t do anything wrong.” After having her demotion rescinded, she returned to the Miami District as one of the headquarters executives overseeing Krome.

The truism told to me by a former Krome officer is fitting: “Screw up, move up.” Indeed, Krome keeps coming under federal investigation. The last one began in 2000, after about a dozen women detainees, many reluctantly and fearing retribution, came forward to accuse some 15 officers of sexual abuse. They told of being fondled, seduced with promises of release—even raped.

Two years later, several of the women who testified before a grand jury have been deported. To “protect” them from abuse, all women detainees were transferred to a maximum-security county jail where conditions are far harsher than for the male detainees left at Krome. Initially, the INS even barred the press from interviewing women there face to face. A Herald attorney had to send a letter threatening to take the INS to court before a Herald reporter and I were allowed to get in to interview three detainees who wanted to talk with us. Thanks to Florida’s firstrate public access laws, it would have been illegal to keep us out of the county facility.

Yet the federal probe has netted only two INS guards who both pled to misdemeanor consensual sex charges, and the investigation into sexual misconduct now appears stalled. Most disturbing is how eerily the women detainees’ allegations paralleled those that sparked a federal investigation 10 years earlier—one that ended without prosecutions or public findings. The message: Detainees who talk get punished, while abusive officers can coerce an inmate into having sex and face a slap on the wrist. Who’s going to find out, anyway?

No wonder questions about policy, its implementation, and misconduct keep cropping up. With post-September 11 security taking top priority, what little scrutiny was aimed at the INS’s treatment of ordinary, nonterrorist immigrants is even weaker now. Today the burning local concern is a policy that the INS denied for three months, before the truth came out in court: Haitians who routinely used to be released to pursue credible asylum claims are now being detained until they are granted legal status or deported. Local advocates had to sue to find out why. The INS testified that it is detaining the asylum seekers to deter other Haitians from taking to the sea to get to Florida. But why would anyone want to keep a deterrent policy a secret?

More than 200 such Haitians have been locked up since December last year when the Coast Guard rescued an overloaded boat in danger of capsizing. Some of them already have been deported. Immigrant advocates are in full swing decrying the inhumane policy. In damage-control mode, the Miami INS is restricting access. It even tried to bar me from visits to the detained Haitian women asylum seekers organized by a state senator and later when INS Commissioner James Zigler toured.

Why was I barred? John Shewairy, the Miami INS district chief of staff, told me that media are not allowed on “show tours.” With remarkable lack of respect for elected officials and for the right of the public to know what its government is doing, he added, “Let the senator have his show somewhere else.”

I went on both tours, along with other journalists. We were lucky that the INS detainees were in a county jail and that a number of elected officials were attending both tours. On each occasion I had to call county officials familiar with the state’s public access law, who then ordered jail staffers to let all journalists in. Prepared for the usual treatment, I carried a copy of the Herald’s letter to the INS that cites specific statutes.

But none of that has lessened the INS’s desire to deflect scrutiny. Nothing but a top-to-bottom shake-up will stop the cycles of inept and corrupt behavior. Structure, staff and culture all need radical reform. Without dogged media pursuit, little will change the INS culture of impunity.

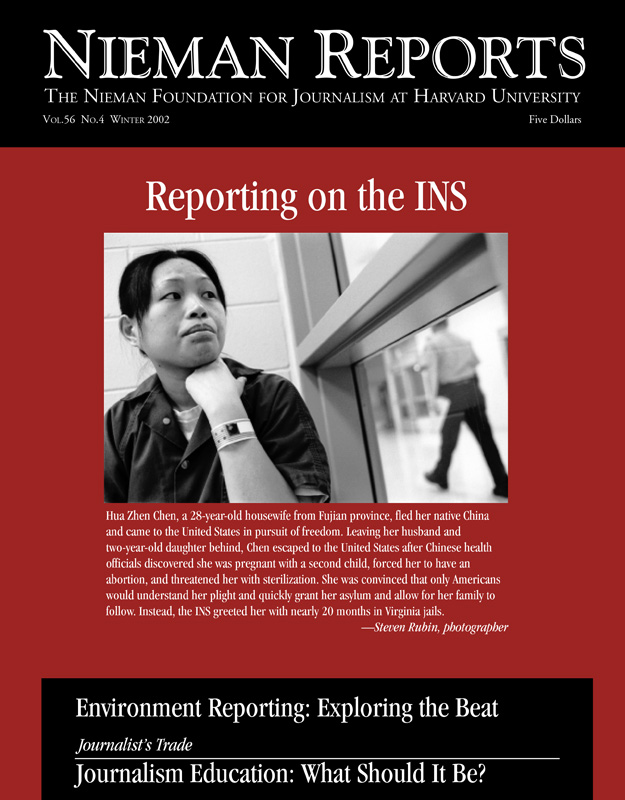

Jesiclaire Clairmont, left, 45, and daughter Lina Prophete, 21, are being detained while her son was given asylum (her sons are pictured at top of page). On the blackboard is the Langston Hughes poem “Dreams.” Photo by Carl Juste/The Miami Herald.

Susana Barciela is an editorial writer for The Miami Herald.