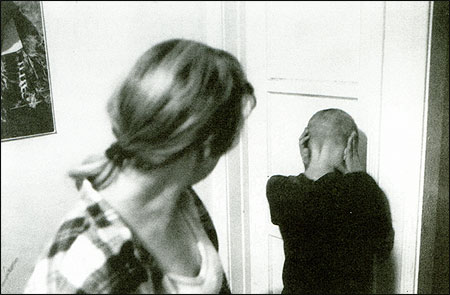

An eight-year-old boy covers his ears and turns away as his father’s girlfriend screams at him in their Long Beach apartment, frequented by addicts. This is one of several images by Clarence Williams documenting the plight of young children with parents addicted to alcohol and drugs that won the 1998 Pulitzer Prize for Feature Photography. Photo by Clarence Williams/The Los Angeles Times.

Is photojournalism dead? It’s a recurring question within the profession these days. But how many times can we check this subject’s pulse before being satisfied that it beats more strongly now than ever before?

Nonetheless, the question must be addressed because, ironically, it is asked most frequently by the same people whose very work tells us that the answer is emphatically no. What they really may be asking is for some assurance that this work continues to be important.

A more subdued climate in the world order brings with it the potential for a more subdued role for still imagery. Softer news and visuals seem to dominate, not necessarily a lamentable turn since it is likely more reflective of the times, rather than a philosophical shift in direction. Intertwined in all of this is the explosion of technology, which has clearly impacted every facet of the profession and, in many cases, added another layer of stress. But none of this should translate to bad news for us. Like so much else these days, photojournalism continually needs to redefine itself.

In the past year or so, the nature of news has changed dramatically with stories like the O.J. Simpson case, the death of Princess Diana and seemingly endless White House travails. For photojournalists it’s a far cry from the decade that began in the late 80’s. From Tiananmen Square to the Berlin Wall and the fall of communism throughout Eastern Europe, we set out on a nonstop excursion from one major upheaval to the next. The Soviet Union, South Africa, the Persian Gulf War, Somalia, Bosnia, Rwanda, Chechnya and more. This was big, serious news. It yielded memorable images. The stories consumed us. Photographers formed tight, emotional bonds; many were injured, and all were scarred when colleagues paid the ultimate price.

In one incident alone, four wire service associates were killed by an angry mob in Somalia. Hansi Krauss of The Associated Press, and Dan Eldon, Anthony Macharia and Hoss Maina of Reuters were stoned and beaten to death. Yet photographers continued to face significant difficulty and danger to capture searing and graphic images from every conflict. And the pages of newspapers and magazines were open to their work. While carefully edited video conveyed similar stories to television viewers, still images stared back at readers, forcing them to study the depths of horror.

So while we might at least understand the genesis of the photojournalists’ current concern, is it correct to ask if the profession is dead or is the real question, “What are we doing to keep it alive?” The answer comes in different forms as photography’s decision-makers in various print markets seek ways to adapt and motivate in a changed news atmosphere.

Marcel Saba, owner of New York’s Saba photo agency, sees the current state of the profession as “changed, different, but alive. I hate when people say photojournalism is dead. We have to help photographers see things differently, to push them to different stories. Magazines are focused more on lifestyle. They’re looking to illustrate stories from religion to hip-hop.”

Saba notes that there may be less demand for certain stories, and it may be difficult to find a home for some, but that the right ones still have a place. He sees the magazine market as very diverse, especially on a worldwide scale, and “there are venues besides the obvious stream of news magazines. Newspapers are a serious market.”

James Dooley, Director of Photography for Long Island, New York, Newsday, couldn’t agree more. “It’s time to call a time-out and take a hard look at the issue of traditional markets. Photojournalism is being done every day in today’s newspapers. But, because it’s being done locally and used locally, you might get the impression it’s not happening. Newspaper photographers are doing the work, and you see it in hard-hitting, provocative and tender photojournalism.”

The example Dooley quickly cites is this year’s Pulitzer Prize-winning series by Clarence Williams of The Los Angeles Times. Williams spent several months in central Los Angeles documenting the harrowing lives of children of heroin-addicted parents. By any measure, the paper gave the series significant display, running it over six pages for two days. And, as the success of the piece speaks directly to the primary journalistic mission to inform the public, it also clearly illustrates that serious photojournalism can, and should, be achieved on the community level.

As they serve as a benchmark of newspaper and wire service excellence, recent Pulitzer prizes for photography bear a closer look. They, too, may indicate somewhat of a shift in approach. The singular icon that crystallizes a major news event (Joe Rosenthal’s flag raising on Mount Surabachi, Eddie Adams’s Vietcong execution, Nick Ut’s napalm girl, to name a few from AP’s past) has largely given way to the photo series that define a story. A notable exception is Chuck Porter’s horrific Madonna from the Oklahoma City bombing. Still, those prize-winning, multiple-picture stories may be telling us something. This year’s spot news Pulitzer went to Martha Rial of The Pittsburgh Post Gazette for a package of searing portraits of survivors of the conflicts in Rwanda and Burundi.

A few might still resist the notion, but there is no question that television news has also had an impact on still photography. The clatter of typewriters in newsrooms across the country has been replaced with the virtual white noise of nonstop, live TV news. We no longer await the still photograph to tell us what happened, but instead expect the still (or stills) to illustrate what we’ve already witnessed. The potential for disappointment is often too great and the pressure on the still photographer even greater. As visual reporters, the primary expectation of a photographer should be to capture the poignancy of any story in a single, compelling moment, drawing the reader onto the page and into the story. Videographers place themselves in no less personal risk and are no less professionally skilled or creative in doing their jobs. Their work is designed to convey a story in a series of edited video clips that leave the viewer with a sense of the overall story. It’s a mistake to measure either medium against the other.

As technologies merge, it is inevitable that the still photographer will simultaneously capture video, and vice versa. The growing need for a multimedia journalist is obvious at a time when newspapers, magazines and broadcast outlets are vying for success in the on-line world. Education and cross-training in all media should be an imperative, and programs should be in place and strongly encouraged at the academic level. Yet too many schools continue to segment journalism degrees to a specific genre such as writing, photojournalism or broadcast and offer relatively few multimedia electives, and much of what is offered is just introductory in nature.

Such integration efforts are under way at many news organizations as once impenetrable walls between disparate departments are falling. But structural change is only a beginning. Some traditional thinking must also change as interdepartmental relationships are reshaped. At a point when readers are inescapably bombarded by information, the critical relationship of words and photos requires a fresh look and new approach. Major news of the day will nearly always drive dominant visual display in any medium. It seems an easy dictum to understand, but too often serves as a source of internal conflict, e.g., best picture vs. best story. Considering the nature of many of the day’s top stories (mega-mergers, White House investigations, IRS abuses and the like) it is incumbent upon photographers and editors to consider visual alternatives to standard story-illustration. Words and photos have to be a collaborative effort, but neither should exist merely to serve the other. Independently, each should do its job to inform and educate readers. If a picture does not advance a story in some way, then it serves no journalistic purpose and merely becomes a design element to break up copy. The destiny of every photo assignment lies squarely with the photojournalist.

“The challenge is greater than ever for photographers to distinguish themselves,” according to Michele Stephenson, Director of Photography for Time Magazine. “Everybody’s getting tired of news conference coverage. People have to look for ways to do these stories better visually.” She posits that the real question is, “how do you get the one image that stands out?

“Photographers are very frustrated because they don’t think there’s any outlet for their work,” Stephenson adds, “they have to turn their passion into projects that are publishable and continue to make compelling images that tell stories in interesting ways.” She feels that the present level of professional queasiness relates to the current period of world adjustment as well as a shift in business trends, especially in the magazine market. However, like Saba and Dooley, she, too, sees newspapers as continuing to make space for good social documentary work.

As photojournalists are examining their role and being called upon to go well beyond the average assignment, they are also working in a world of constantly changing tools. And the impact of technology on the entire profession is undeniable. Digital photography is an opportunity for photojournalists to take their craft further, spend more time photographing and control the editing of their work.

Only a few years ago, photographers found themselves traveling to assignments with full darkrooms in tow. Excess baggage knew no limits as large crates contained an enlarger, developing trays, printing paper, chemistry and an assorted tangle of phone and electric wires and jacks. As it goes, getting there was half the fun. Upon arrival, resourcefulness was the watchword. Every setup took time, time that he could have used photographing more of the story. Today, the traveling kit may be little more than a laptop computer and scanner. Compact portable satellite phones replace the need for landlines and, in most cases, hours have been reduced to minutes.

Technical advancements have had clear applications on any remote assignment, whether it’s abroad or around the corner. Newspapers are now able to provide readers with color action from late news and sports events from any location, something that would have been impossible before digital transmission.

Of course, this change is neither complete nor without its complications. “More” and “faster” are words that demand careful consideration in the new world. “Quality” and “content” must, as always, be the priority. An editor’s prerogative should be to seek a wide choice before deciding on usage. And selection is what they get. On an average day, AP provides upwards of 250 images in its PhotoStream report. An editor receiving other wires and supplementals could easily double that number. (It’s ironic at a time when the viability of the medium is held to such questioning that so many images are hitting the editor’s desk every day.) The technology enables editors to view images as selectively as they define. And seeing more on a given topic could translate to a greater chance for multiple-picture use rather than single-image illustration of a story. But, again, quality and content remain the unequivocal standards by which the quantity is measured. By extension, they remain unequivocal standards of photojournalism today. Technology may be as transitional as the news, a fact that neither alters nor deters the mission.

Is photojournalism dead? Absolutely not. Now, more than ever, the challenge for photojournalists is to pursue their vision with a renewed sense of the passion that drives them to do what they know best.

Vincent Alabiso is Vice President and Executive Photo Editor for The Associated Press. He has been the head of AP’s photo operations since 1990. Under his direction, AP Photos has been honored with six Pulitzer Prizes. He returned to AP after a three-year stint as Director of Photography at The Boston Globe. While at The Globe, the paper was cited for best use of photos in the National Press Photographers/University of Missouri Pictures of the Year competition. From 1981-1987, he worked at the AP, first as Boston Photo Editor, before becoming New England Photo Editor. He has been a judge for the Overseas Press Club, the National Press Photographers Association and Pictures of the Year photo contests, and taught photo editing at Boston University School of Journalism. He is also a member of the Board of Directors of the Eddie Adams Workshop. Alabiso received a journalism degree from Northeastern University in Boston in 1969. He began his career as a staff photographer at The Patriot Ledger in Quincy, Mass.

Vincent Alabiso is Vice President and Executive Photo Editor for The Associated Press. He has been the head of AP’s photo operations since 1990. Under his direction, AP Photos has been honored with six Pulitzer Prizes. He returned to AP after a three-year stint as Director of Photography at The Boston Globe. While at The Globe, the paper was cited for best use of photos in the National Press Photographers/University of Missouri Pictures of the Year competition. From 1981-1987, he worked at the AP, first as Boston Photo Editor, before becoming New England Photo Editor. He has been a judge for the Overseas Press Club, the National Press Photographers Association and Pictures of the Year photo contests, and taught photo editing at Boston University School of Journalism. He is also a member of the Board of Directors of the Eddie Adams Workshop. Alabiso received a journalism degree from Northeastern University in Boston in 1969. He began his career as a staff photographer at The Patriot Ledger in Quincy, Mass.