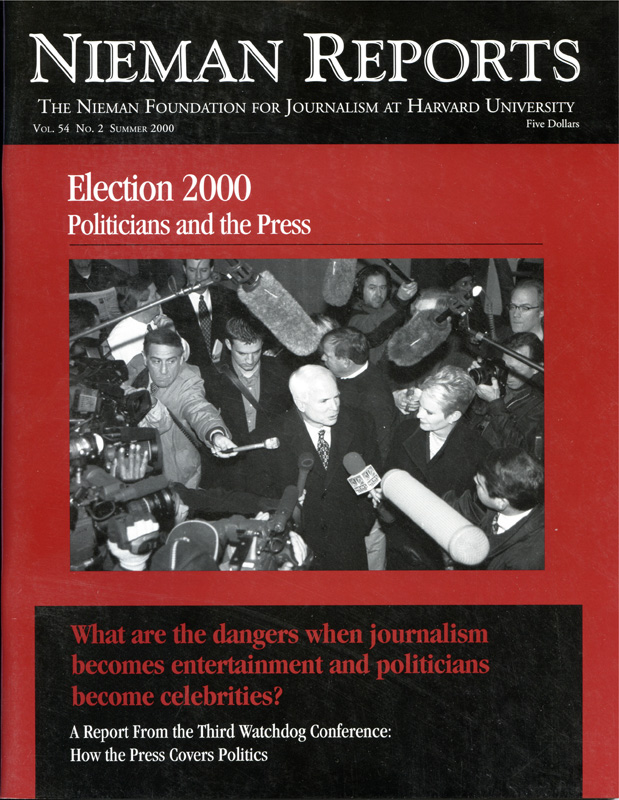

Keyes jumps into a mosh pit in Des Moines, Iowa. Photo by M. Spencer Green, courtesy of AP Wide World Photos.

“The so-called second tier, if you will….” —Wolf Blitzer, CNN, during the New Hampshire primary campaign.

Into the chaos of the media filing center after last fall’s Republican presidential debate at Dartmouth College walked Alan Keyes. The unlikely White House contender mounted the podium and waited for post-event questions. There were none. And he couldn’t stand it. Before huffing off, Keyes, the only African-American seeking the nomination of either major party, denounced the assembled journalists, almost all of whom were white, as racists.

Keyes, not widely known for his media skills (except for playing his race for all it’s worth with the famously self-conscious national press), did not know the difference between benign neglect and deadline pressure. But there was, in fact, nothing most journalists wanted to ask Keyes on a spot basis, except perhaps what he was doing in the debate in the first place—and what they were doing paying any attention to him at all.

The strange scene in the loud, crowded Dartmouth hall helped to frame one of the more interesting questions of the 2000 campaign: Have minor candidates such as Keyes been covered too much or not enough? Hardly anyone thinks the coverage has been just right.

The same question, without the entangling racial implications, applied to Keyes’s fellow candidate and conservative activist Gary Bauer.

Here were two guys who never had won a race for city council, much less some significant state or federal office, which has come to be seen as an entry-level qualification for the presidency. They also failed to pass muster on two other important criteria that journalists consider before bestowing significant coverage: campaign funding and significant backing from party figures of consequence. Both are imprecise but seemingly valid early measures of popular and political establishment support.

Bauer most recently had been Director of the Family Research Council, a conservative group strong in its opposition to abortion. Keyes, who also sought the Republican nomination in 1996, was a failed U.S. Senate candidate in Maryland and sometime talk show host. Each conflated modest postings in the Reagan administration, supplemented by subsequent roles on the Republican Right, into presidential campaigns that got them into nationally televised debates, if not consistent print or broadcast coverage.

Abraham Lincoln and Steve Forbes are to blame.

Lincoln, with his string of often unsuccessful attempts at office before riding out of Illinois to save the Union, offers an appealingly cautionary tale about disregarding the unlikely candidate. Does David Broder or Joe Klein or Tom Brokaw want to have it on his conscience that by some sin of omission he denied the nation the next Great Emancipator?

This is, of course, historical sophistry and ignores the many differences between then and now, not least of them the pre-Civil War proliferation of political parties and the lack of truly national media in the mid-19th century. Lincoln, viewed more properly, is the candidate who proves the rule that prior top-level governmental experience is needed before taking on a national campaign that deserves to be taken seriously.

(Perhaps it’s worth noting that U.S. Representative Tom Coburn, the Oklahoma Republican who became Keyes’s only congressional endorser, likened Keyes to Lincoln, saying the social conservative understands America’s “underlying national crisis.” Keyes did not shrink from the comparison.)

Forbes, the multimillionaire publisher, got us into the current mess. Here was a guy with so much of his own money that in 1996 he bought his way into semi-acceptability as a presidential contender. The field of more established Republican candidates was so light four years ago that the media (and some voters) took Forbes and his flat-tax proposal sort of seriously for about four months. Perhaps foretelling the party’s (and Bob Dole’s) problems in November, Forbes even lucked his way into a couple of early primary victories before quitting that race and beginning immediately to retool for 2000.

This time around, Forbes and his bankbook were back. He had not only a canny strategist, Bill Dal Col (a repeat from 1996), but also a superbly organized media staff packed with well-known young Republican agents with whom reporters love to share a drink or rumor (if not deeper ideological discussions).

Forbes, too, had been a Reagan appointee, but he had never sought, much less won, any electoral office except the presidency. So if journalists were going to once again buy into his well greased act, how could they in good conscience totally write off (as many would have liked to) Keyes and Bauer?

Additionally, Keyes carried a cautionary warning for the media from his 1996 campaign. After being cut out of a couple of debates, he encamped outside an Atlanta television studio until the cops were called. As The Economist this year remembered the scene: “The embarrassment of seeing the country’s only black presidential candidate carted off…in handcuffs so traumatized the networks that they were never likely to make the same mistake again.”

As far as print reporters were concerned, some seasoned journalistic hands believe younger practitioners simply lacked the nerve or judgment to pare the list down to size.

“When I was covering the New Hampshire primary,” recalled Martin Nolan, the highly regarded Boston Globe correspondent, “Gary Bauer would have been listed as one of the minor candidates, one of the guys in an Uncle Sam suit.”

How the minor candidates were handled by the media has been a minor motif in campaign coverage.

Time’s Margaret Carlson noted after New Hampshire the call for culling minor candidates from future debates. She seemed to object, advancing the offbeat view that politics should be some test of ad lib ability or even situation comedy.

For Republicans, she said, “there would be no spontaneity without the understaffed challengers.” As for the charismatically challenged Gore-Bradley combo, she observed: “Just as Lucy and Desi needed the Mertzes, the Democrats could use a foil or two onstage.”

At various points in the campaign, important media outlets hustled to catch up on the also-rans, especially on Keyes.

Perhaps the most thoughtful piece on Keyes ran in The Washington Post two days before the Iowa vote. It was by the Style section’s political troubadour, Kevin Merida, who is black, and concluded with an assessment from historian Roger Wilkins of George Mason University, who is also black.

Wilkins objected to what he called Keyes’s “almost profane” misuse of the slave metaphor, an objection sparked by several Keyes antebellum references, including a jibe at the Republican frontrunner as “Massa Bush.”

“There are few people who have run for President in my lifetime with slimmer credentials for doing so,” Wilkins said. “Who is this guy?”

Bauer and Forbes dropped out in regular order, just like losers immemorial in Iowa and New Hampshire.

But Keyes, with nothing to lose and an ego to feed, pressed on, becoming a sort of Greek chorus playing against Bush and Sen. John McCain in the nationally televised (at least for cable subscribers) debates to which he continued to be invited.

In the Los Angeles debate in early March, Keyes was asked to explicate the limited success of his effort.

“You have been very eloquent through this campaign,” noted questioner Doyle McManus, Washington Bureau Chief of the Los Angeles Times, but the Republican faithful “are not flocking to your standard.”

“I’d be willing to bet a great many of them have no idea that I’m running because of the media black-out on this campaign,” said Keyes, reverting to his beloved indignation. “I’ve always found it interesting. You guys play the game: Put the mask over the eyes of the people and then ask why they don’t see me.”

Except for the racial dimension, Keyes was advancing the long-held view of minor candidates: No coverage means no cash, no endorsements, no traction. It’s admittedly fertile ground for a vicious circle, but for journalists, is there a requirement to provide the same playing field for a relative unknown as for an experienced senator or a big-state governor?

Keyes certainly had his view of the issue. In his summation in the Los Angeles debate, Keyes returned to one of his favorite themes.

“The one question that came up tonight is worth answering: Why am I here? You know the reason I’m honestly here? It’s because with the majority of people in the Republican Party, I’m the sentimental favorite. I’m the one you’re all listening to. You know I’m saying what’s in your heart. You know that I speak the truth, the true bedrock conservatism.

“I do it better than anybody who has appeared in these debates, and it’s the one reason that my colleagues did not feel that they had the strength to stand up and say, ‘Kick him out.’ You see, because they know that would rouse your ire.”

Maybe. Maybe not.

Cragg Hines, Washington Bureau Chief of the Houston Chronicle, is covering his eighth presidential campaign.