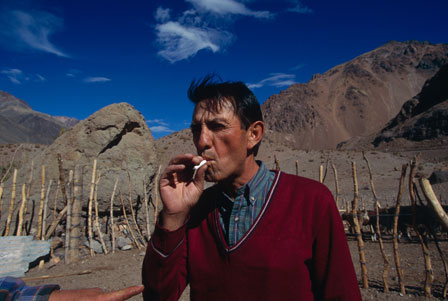

All photographs by Pablo Corral Vega, from the books “Andes” (National Geographic, 2001) and “25” (Latina Editorial, 2007).As in the iconic scene from “The Wizard of Oz,” the curtain obscuring the secrets of photography has been pulled back. The wizard, the alchemist, the powerful conjurer of images, the artist of light and shadow is shown to be just a man. His old tricks no longer amaze anyone.

This is an extraordinary moment for photography but a terrible moment for photographers. Photography is the undisputed language of the 21st century, but it is increasingly difficult to be a professional photographer, to make a living from photography. We lost our monopoly on the image, the secrets of its magic.

Este artículo está disponible en Español.Never before have so many people had access to a camera. There are now billions of cameras built into cell phones—a phenomenon that only began in 2000. This radical democratization of photography is not happening only in developed countries; there are large populations of people with limited means in India, Africa and Latin America using these cell phones.

According to Ramesh Raskar and his team of scientists at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, in less than a decade only a few professionals and serious amateurs will use dedicated cameras because improved quality in cell phones will make almost all traditional cameras obsolete.

Prior to this proliferation of digital imagery, professional photography was the stronghold of a few who possessed expensive equipment that was difficult to handle. Only those who knew what sort of film to buy, how to expose it correctly, and which specialized laboratories would develop it properly could produce truly high-quality work. The floor has fallen out from under professional photographers; the zealously guarded advantage held by those with arcane know-how simply disappeared. Anyone can now buy the same reasonably priced camera professionals use, and without significant effort achieve technically similar results.

The most radical transformation isn’t the way we capture images, but how we share them. Previously we had to print pictures on paper—an expensive process—and then we had to get the physical object to other people. This limited the uses and the potential viewership of the images. Now we can make endless digital copies of our files. We can send our photos via e-mail, put them on Flickr, add them to Facebook, or create exhibits with online gallery spaces like deviantART. Of course, now we can also make prints in sizes and on surfaces that were previously unimaginable.

This tumultuous change is reminiscent of what happened after the invention of the printing press in Europe. Before, only a few could read and write. Printing democratized the written word, pulling it out of the erudite confines of the monasteries. Writing came to be used for countless everyday purposes.

The language of the image, which was dominated by a few, will come to be used in unexpected places and to fulfill unexpected social functions. Its increasingly widespread use will bring more power and vitality to the image and to society.

But this process will necessarily lead to the trivialization of photography. We are already inundated with images, and it is difficult to recognize the few that evoke or transform, the pictures that have something to say, that are loaded with meaning. There are many such images, without question. But now it’s easier to view and share photos. There are many more of us helping to create this visual heritage. But to find those extraordinary images, which have the capacity to become personal or collective symbols, a sort of quiet is needed. That quiet is, itself, becoming increasingly scarce. It is easier to save every photo, share every photo, even if we end up flooded, overwhelmed by the excess.

As professional photographers, we must use this crisis to regain our humility and ask ourselves a basic and urgent question: Why do we take photographs? Money or fame certainly will not be reasons to follow this path. I wonder how many professionals will be able to continue making a living with this work.

Most of us take pictures because we want to remember, affirm affections, and leave a record of our connections with others, visible proof that we were, we loved, we celebrated. Some take photos to show beauty, asking others to look with amazement at this complex world—at once painful and wonderful. We take photos because we want to share, because we want to tell others, “Look, pay attention, my eyes enrich yours.”

My reasons for taking photographs are quite simple. I take pictures because it makes me happy. Photography has taught me the immense value of being present, being where I am, and paying attention to what happens around me. The camera is a bridge that connects me with everyone else, a passport that allows me to enter other cultures, other worlds.

The magic of photography is perhaps simpler than we thought. It requires no powerful equipment or secret alchemy. It is a language, like others, to talk about what it is to be human. It is a way to recognize one another, to remember the importance of seeing with kindness and poetry.

Pablo Corral Vega, a 2011 Nieman Fellow, is an Ecuadorian photojournalist whose work has appeared in National Geographic and The New York Times Magazine. He has published six books of photography, including “Andes,” for which he traveled the length of the mountain range and took many of these photos. He is founder and director of Nuestra Mirada, a network of Latin American photojournalists, and organizer of Pictures of the Year Latin America Visual Journalism Contest. This essay was translated from Spanish by Ted O’Callahan, a freelance writer and translator as well as an editor for the Yale School of Management’s Qn magazine.